It was never unreasonable to suppose that the pandemic — and lockdown — would lead to a crisis in mental health. Quite apart from the suffering of those most directly affected by the disease, the stress and isolation suffered by entire populations was expected to have a serious impact on well-being.

Increasingly, we now have hard data to analyse. A new study by a team of researchers led by Zachary van Winkle of Sciences Po and Oxford University looks data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe; and across 11 countries finds an “unprecedented decline in feelings of depression” that coincides with the first wave of the pandemic last year.

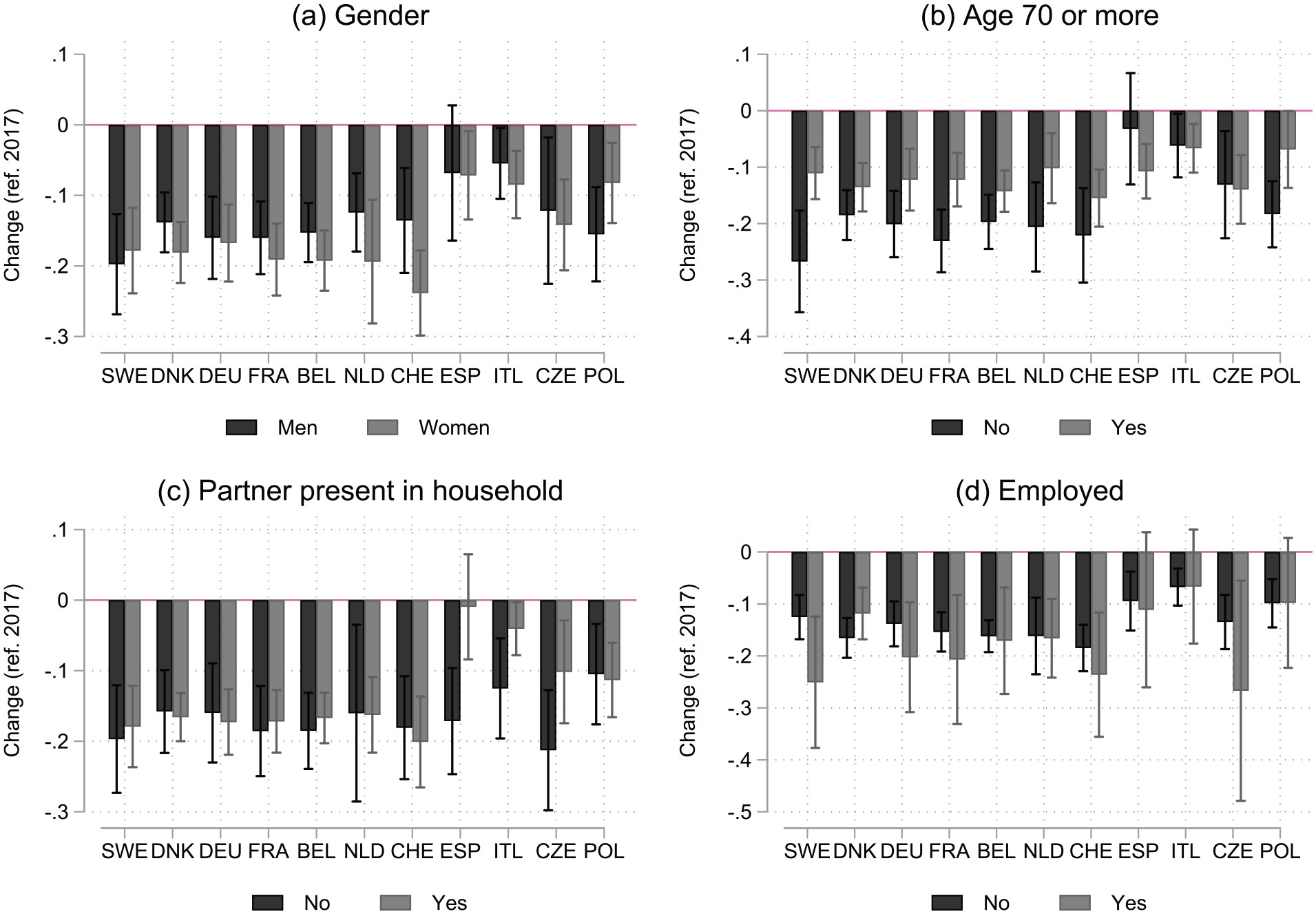

The dataset stretches back for more than a decade and this fall was “larger than any previous observed change”. Furthermore, there were “no systematic within-country differences by socioeconomic characteristics, chronic health conditions, virus exposure, or change in activities.”

Putting it mildly, the authors observe that these findings “challenge the conventional wisdom.”

Before trying to find an explanation, it’s worth pointing out a few things. Firstly, this is just one study — and we need others that provide a similarly comparative and longitudinal overview. Secondly, it concerns reported feelings of depression in the over 50s — and we need to pay attention to other mental health conditions and age groups too. Thirdly, the data only extends to the first wave of the pandemic and covers only one part of the world (Europe).

It should also be said that these are population-level studies and even if an overall decline in depression has taken place it doesn’t mean that particular individuals haven’t suffered.

Nevertheless, if the results of this study are at all indicative of the bigger picture, then we do need explanations. It would seem extraordinary that something as calamitous as the pandemic and as constricting as lockdown has coincided with a marked improvement in (aspects of) mental health.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeThe 50s is a time when you begin to hate your job but are too old to get another one. You have arrived at a level where, when you first started work, you would have had your own office but now you are crammed into open plan and hotdesking listening to young idiots talking ridiculous management speak. The walls are plastered with rubbish from Stonewall about ‘gender’ and you are terrified to make a joke in case one of the blue haired and humourless take offence. You spend two hours a day on filthy, overcrowded public transport and you have permanent constipation because you never have the time or the privacy to go to the lavatory properly. Your knees and hips hurt and you rarely see the home that you have slaved for years to pay for in daylight. You hate your parents but you are stuck with visiting them and listening to their moaning and repetitive questions. Your whole life is one of suppressed anger and tedium.

Suddenly you are not allowed to go to the office. You can work from your own house and never have to see a Stonewall poster or someone with blue hair. You can have lunch in your own garden and listen to music if you want to. You have an excuse not to visit your parents and can spend as long as you like on the loo. Suddenly you are not angry anymore and, as depression is suppressed anger, you are not depressed either.

The challenge will be how to go back to normal whilst keeping the good bits. Homeworking, setting boundaries with parents and standing up to the workplace ‘woke’.

This exactly.

A nice description of the 50s haha. I remembered them as being a notch better. But then, I had my own office and could work at home anytime 🙂

Write a book, please.

Interesting! Though I would imagine this point will be key in any wider study:

Those over 50 are:

In short there are a lot of the worst elements of lockdown that simply won’t affect the majority of over 50s, as much as I would like the pattern to be matched across a wider age range.

(That list grew and grew as I thought and wrote!)

Indeed! From the journal:

“For example, increased subjective well-being during the first lockdown in France was found mostly among socioeconomically advantaged and employed individuals (Recchi et al. 2020).”

An excellent summation. I would add that for many they must have also been less likely to worry too much about others very negatively affected. I have found a lot of people are incapable of reflecting on others in respect of lockdowns.

I think what isn’t factored into/visible in those studies is what restrictions were actually in place in each country at each data point.

In Germany, you could pretty much always go round to someone else’s house and see your friends. In the UK, that was illegal for many months. Sweden had practically no restrictions for most of last year, while Spain had a phenomenal number.

I don’t think you can really compare supranationally without that information, because a large part of what causes increases in depression (and significantly more so for suicide) is social isolation.

The data sets also cut off in August, which was a hopeful time in Europe for COVID. It was seen as on the out. Now it is presented as ever present and never going away (with certain people wanting the same for restrictions). I think those are some quite significant changes in how our minds cope with the day to day.

That depression may be measured as lower in the first wave isn’t altogether surprising.

We were operating under a new threat, with neurotransmitters related to fright flight and fight overrriding other mechanisms.

These data are meaningless. The question is, what happens after the wave has passed? What happens when an emergency system becomes the norm?

Mental ill health took 3 months to manifest. And in the January lockdown, mental ill health arrived in days, not weeks.

I am singularly unconvinced by this argument.

Interesting findings. I believe that a factor in any changes in mental health during lockdowns (regardless of age) will be whether someone is introverted or extroverted. Extroverts probably suffered from the social isolation and missed the kind of interaction-driven work environments that modern offices entail. On the other hand, introverts probably find all the hubbub of an office with all its meetings and pointless smalltalk tiring. Lockdown might have given them a chance to work in a way more suited to their personalities – and that will have had a positive impact on their mental health.

i agree . Introverts are not too happy about endless queuing in traffic/buses etc either , rushing of any sort (inc bowel movements), and are well adapted to entertaining themselves….without having to hang out with often pesky people (Speaking from experience ).

Having experienced the opposite, being stuck at home for 18 months, hunched over a laptop, I can only be surprised at how much the average person hated their previous life. I suggest this mainly concerns working life. I knew most people hated their jobs and working day, but not how much.It’s brought home to me how priviledged I was. I now know how the other 95% existed.

Sounds like those polled were public and financial sector full time middle aged employees.

I wonder if this research actually “controlled” for anything.

If it didn’t, I’d suggest that any conclusions relating to it are probably meaningless.

e.g. a similar pitfall is visible in studies trying to claim increased productivity for working at home, by including the opinions of people who hate commuting (or office life).

Not convinced by this research. There is much spurious social (and other, medical, you name it) research around, and poorly conceived and executed surveys. It is always tempting to ‘find’ something unexpected and ‘counterintuitive’.