Yesterday’s release of the trailer for Joker 2: Folie à Deux has already reignited the discourse over the first film. Todd Phillips’s 2019 Joker was one of the most controversial films of the last decade, though whether this is justified is another matter. The dispute mainly came out of the hand-wringing of certain cultural commentators, who lambasted the film for glorifying the misogynistic philosophy of inceldom — even for supposedly inspiring acts of violence in the style of Elliot Rodger and the 2014 Isla Vista killings.

When cinemagoers saw the film, it wasn’t exactly the alt-Right incel call to arms much of the contemporary discourse portrayed it to be. The protagonist, Arthur Fleck, is in every sense a social reject. He has no friends. He grows up without a father figure. His only half-meaningful relationship is with his mother, and his uncontrollable tendency to break into delirious laughter is a pretty reliable social deterrent.

But Fleck’s romantic and sexual misfortunes are only part of his larger ambition to be recognised by a society that sees him as nothing, and aren’t crucial to his path towards violence and chaos. Joker is a character study, obviously borrowing from Martin Scorsese films such as Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy, of an archetype that has been with us since the advent of modern society: the alienated and socially disconnected man prone to ressentiment.

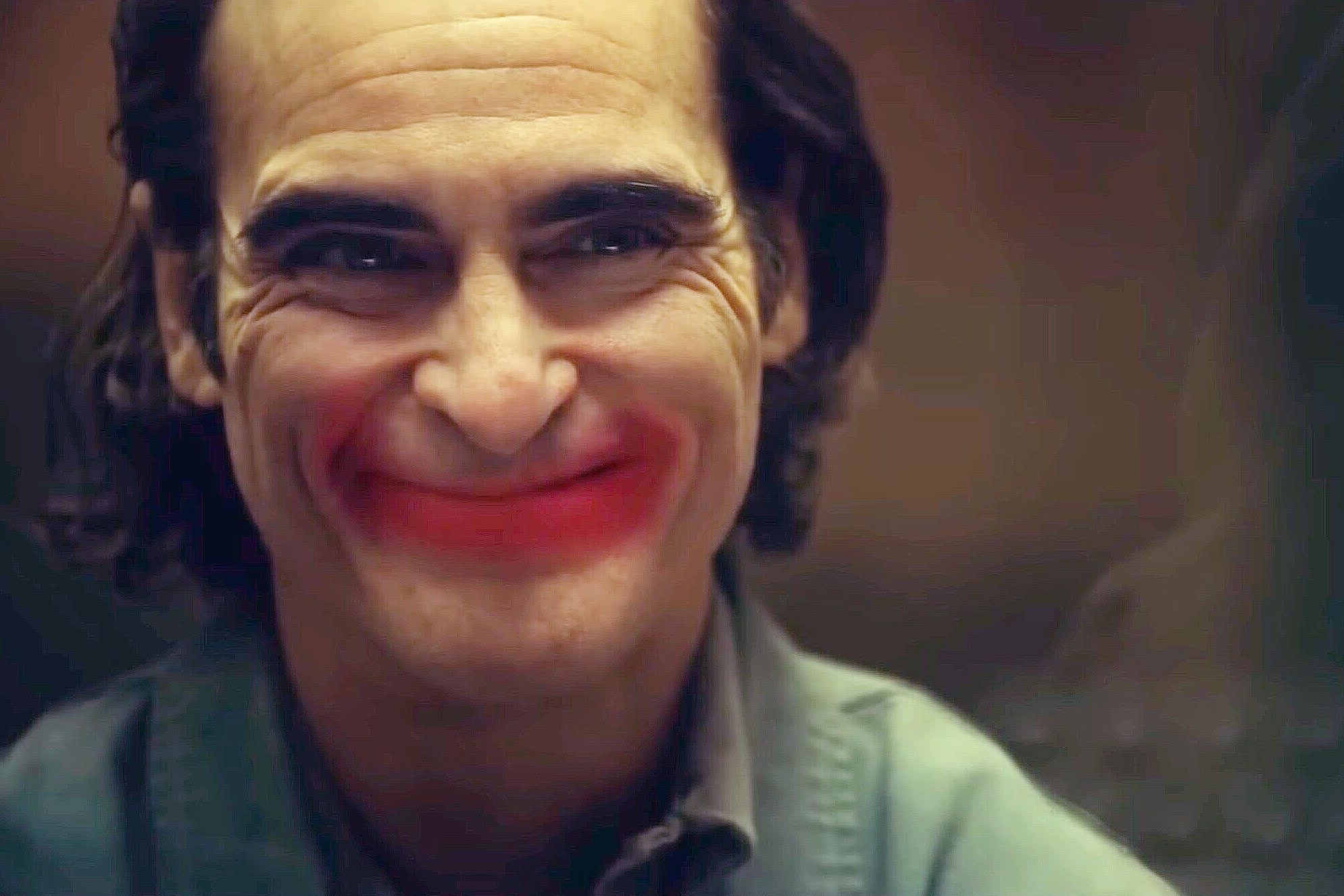

Nonetheless, the first film did play a role in influencing the discourse around incels, making them more realistic, nuanced figures. Despite all the moral panic — or perhaps because of it — Joker became the highest-grossing R-rated film of all time and won star Joaquin Phoenix an Oscar. If the character of Fleck resembles an incel, this exposure allowed viewers to find some sympathy for a group of people who had previously been maligned.

In recent months, articles and academic reports have been relatively balanced, even empathetic, including a study claiming that incels are more likely to be autistic. Joker encouraged us to follow Spinoza’s dictum to not laugh, nor weep, nor hate, but to understand a phenomenon like incels, because there are deeper reasons behind it. It is more than just a movement made up of bad men.

The people we call “incels”, and those who struggle to form social and romantic connections, are largely products of an alienated and atomised society. This crisis of civil society has manifested itself in multiple ways, whether in the weakening of traditional family structures, a friendship recession, people entertaining themselves more at home than outside of it, or in younger people having less sex with fewer partners than before. Anton Jäger, in a defence for Jacobin of Robert D. Putnam’s Bowling Alone, astutely argued that this is the result of capital’s insatiable drive to “diminish” collective life in order “to find new avenues for accumulation”.

What will be interesting about the Joker sequel is that there is a change in dynamic. We know that Arthur Fleck, the Joker, finds his female companion in the villainous Harley Quinn. How will this change him? Will a female influence make him more “normal” and psychologically disciplined? Or will he become even worse precisely because he’s found someone just as disturbed and chaotic as he is, someone who shares his social alienation and craving for recognition?

Folie à Deux may or may not provide satisfactory answers to these questions, but it is bound to be viewed as an extension of our continuing fascination with incels.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe