With nominations closing earlier this week, the good news for the six candidates vying to be the next Conservative leader is that, throughout its long history, the party has usually bounced back from substantial defeats. On the first three occasions in the last century when the Conservatives suffered a pasting at the polls — 1906, 1945 and 1966 — they went on to gain an average of 94 seats at the next election. Every time, the party stared into the abyss before coming roaring back.

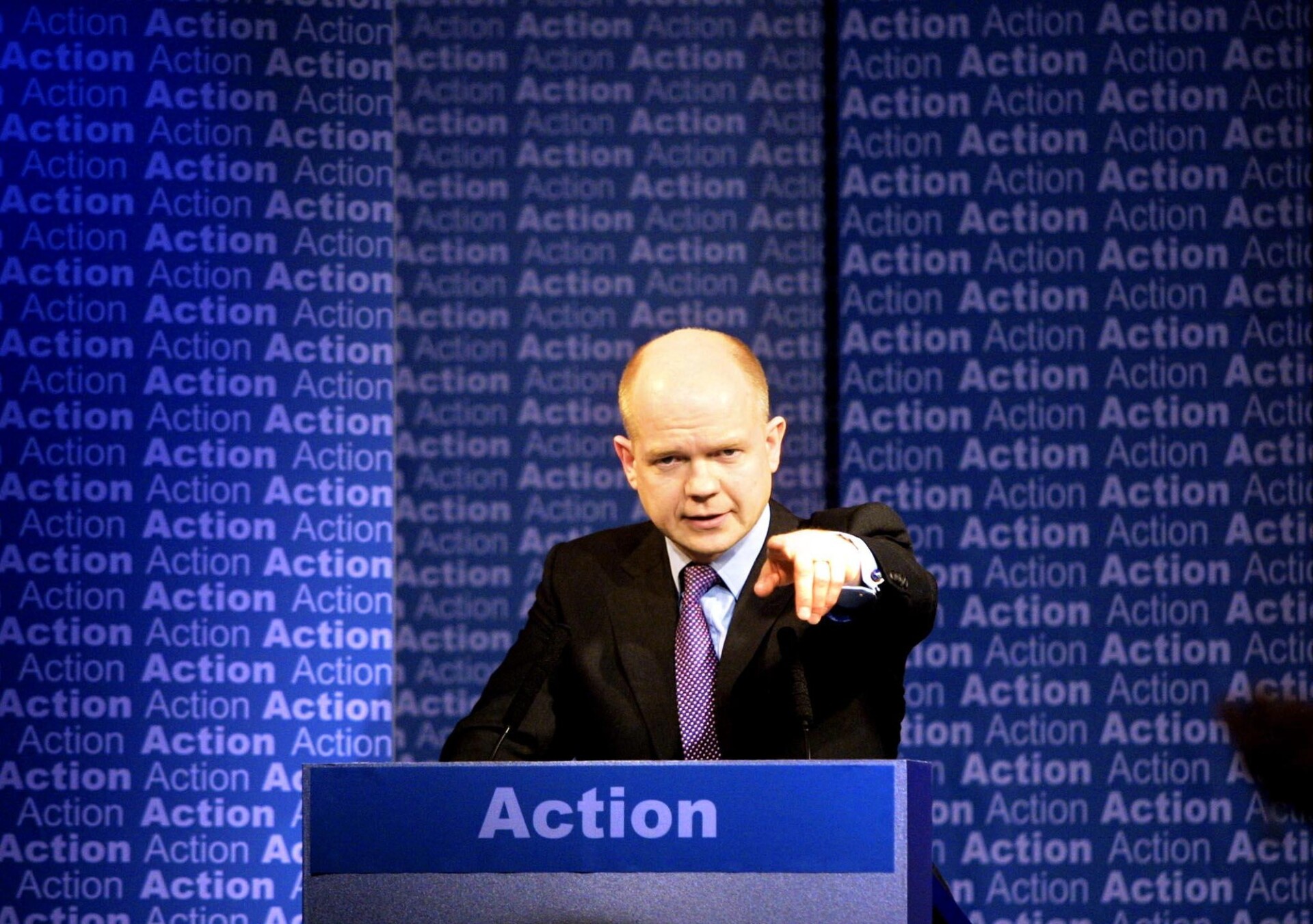

Then 1997 happened. After Tony Blair’s landslide victory, until recently the Conservatives’ worst result since 1832, the pendulum that had so decisively swung against the Tories refused to swing back. Voters went to the polls in 2001 and rewarded the party, led by William Hague, with just one extra MP and another big defeat.

What lessons can today’s Tories learn from a quarter of a century ago? The first is the need to have your best players on the pitch. Hague inherited just 165 MPs after the shellacking of 1997. Yet of the MPs who remained, too many were reluctant to play their part in rebuilding the party. Ken Clarke, the former chancellor and one of the party’s few nationally popular figures, refused to serve in the Shadow Cabinet. Others followed his lead. By the midpoint of the parliament, Hague’s original picks to shadow the chancellor, home secretary and foreign secretary had all departed for the backbenches.

The next Conservative leader will start with an even smaller parliamentary party — 44 fewer seats than after 1997 — and will be unable to call upon any of the record number of Cabinet ministers who lost their seats on 4 July. That includes two-time leadership candidate Penny Mordaunt, as well as the former secretaries of state for education, defence, justice, transport and culture, many of whom would have played a big role in the party’s post-election recovery.

Successfully mustering the energies of 121 MPs against a government with over 400 will be an almighty challenge for the next leader. If too many of the remaining Tory big beasts refuse to serve on the front bench, it might prove an impossible one. All of the leadership candidates have an interest in this. A joint pledge to loyally serve in the Shadow Cabinet, should they be asked, would be a useful sign that the party has learned a key lesson from its previous experience in Opposition.

Hague’s other great problem — familiar to almost all Tory leaders since — was insecurity in the role of leader. Uncertain of support from his MPs, too many of whom failed to process the magnitude of the Conservative defeat, he stood up to his party too little and instead gave it what it wanted. This led to a policy platform too focused on Europe — the party’s own obsession — and not the bread-and-butter issues that decided the next election.

The Conservatives’ recovery in the years ahead will be seriously stunted if the next leader also has to spend their time securing their own position. It’s not difficult to imagine how this could once again lead to a fixation on a new shibboleth for the Right, such as Britain’s relationship with the ECHR, at the expense of voters’ other priorities.

The ECHR, especially Tom Tugendhat’s surprise willingness to consider leaving it, dominated headlines in the opening phase of the leadership election. If it continues to do so, it will signal a party engaging in conversation with itself and not the British people. Worse, as in 2001, it might lead the Tories to go into the next election with a robust policy on Europe but too little to offer on the economy, NHS and education. The result could well be another landslide defeat.

History suggests that the Conservatives could make a strong recovery at the ballot box next time. But the experience of 1997-2001 serves as a warning not to take this for granted. The pendulum is not guaranteed to swing back; and if the party repeats the mistake of a quarter of a century ago, it won’t.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe