What is the proper relationship between corporations, society and government? This question is increasingly urgent as businesses worldwide plead for government support to get them through the economic disaster of coronavirus. This week’s long read pick, by Matt Stoller at American Affairs, offers some indications as to how (at least in the United States) this debate may develop as we emerge from lockdown.

Business leaders are confronting ‘a crisis in corporate America’. Productivity is foundering, energy companies seem unable to stop setting bushfires in California and social media is inflaming political polarisation. Stoller traces the evolution of this situation through the regulatory changes that brought it about.

In the 1980s, Stoller writes, ‘the American economy was still in many ways a New Deal society’: unionised, dotted with small businesses, highly structured regulations governing utilities, and public infrastructure. But international corporations were increasingly struggling between these obligations and the intensifying aggression of global competition.

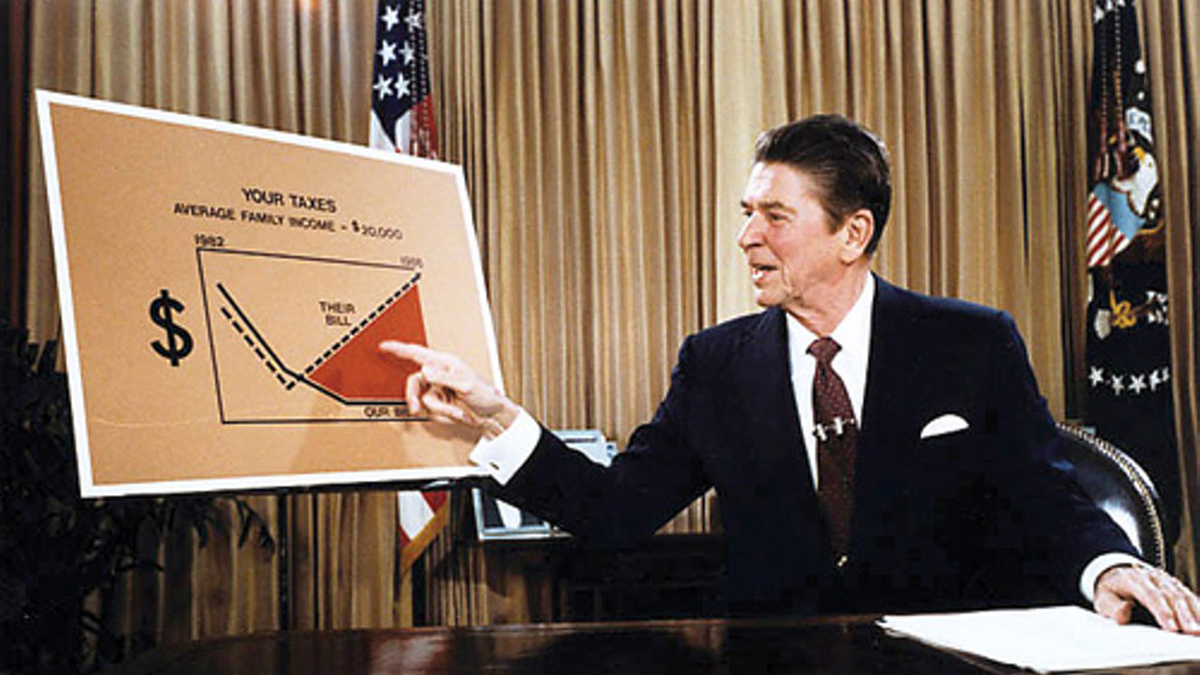

The Reagan-era Business Roundtable argued that business was capable of meeting its social obligations without this raft of regulations. In response, government cut social spending, deregulated industries and relaxed antitrust rules. Industries consolidated, strikes reduced, inflation stabilised and stagnant areas of the economy roared to life.

But, as Stoller notes, the new normal ‘also began weakening the bonds between CEOs and the corporations they ran’, and over time saw ‘the end of stakeholder capitalism and in some ways the erosion of the CEOs’ own power thanks to the replacement of CEOs by financiers at the top of the food chain.

Leveraged buyouts, asset-stripping and the new age of private equity drove economic concentration even as their advocates paid lip service to competition. Stoller shows how the Clinton administration, ostensibly left-wing, embraced the financiers even more enthusiastically than Bush had before him. The days of deregulation, offshoring and the deliberate ceding of manufacturing to China arrived, even as the fall of the Berlin Wall encouraged business leaders and those benefiting from globalisation to hail ‘The End Of History’. Meanwhile, the benefits seemed sufficiently widespread that “financial power, markets, and social justice seemed to go hand in hand.”

International terrorism, the Great Crash, the rise of China, the opioid epidemic, ‘flyover country’ and now coronavirus have exposed in ever more painful form the hubris of that millennial moment. After a decade of financier-driven governance dedicated to short-term value, Stoller observes, corporate assets and infrastructure are creaking, while the companies are running low on R&D, social capital, long-term vision and productivity. Meanwhile, the American population as a whole is tiring of laissez-faire leadership: “They want to be governed.”

Even the Business Roundtable, driver of the laissez-faire model, has disavowed the ‘shareholder value only’ vision of corporate purpose in favour of a vision that “includes customers, suppliers, communities, employees, and shareholders in a stakeholder model.” The question, Stoller suggests, is what is to replace the disintegrating laissez-faire consensus. Will it be a ‘corporate liberalism’ that amounts in effect to governance shared between big business and the state? Or a new mobilisation by government to break up overmighty corporations in favour of broader competition and a thriving marketplace of smaller businesses? Stoller is sceptical of ‘corporate liberalism’ as a force for the public interest, saying of the giant corporations:

Corporatism or activist government in the interests of the public and small businesses? This, as Stoller sees it, is the new battleground in corporate America. One way or another though, “The libertarian era of financier power is over.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe