Last week the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) released its November Economic and Fiscal Outlook. The new forecasts got particular attention because they accompanied the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement. The OBR forecasts generated some scary headlines, with the papers focusing on the grim figure for household disposable income that the OBR said would fall some 7% in the next two years.

Yet both the budget and the forecasts weren’t really that concerning. It appears that both the Treasury and the OBR pulled off an impressive public relations trick: they managed to convince the average Briton that the situation was bad, but at the same time they released a budget and forecasts that were less doom-mongering. Most importantly, they appear to have buried from view some of the worst economic consequences facing the British people.

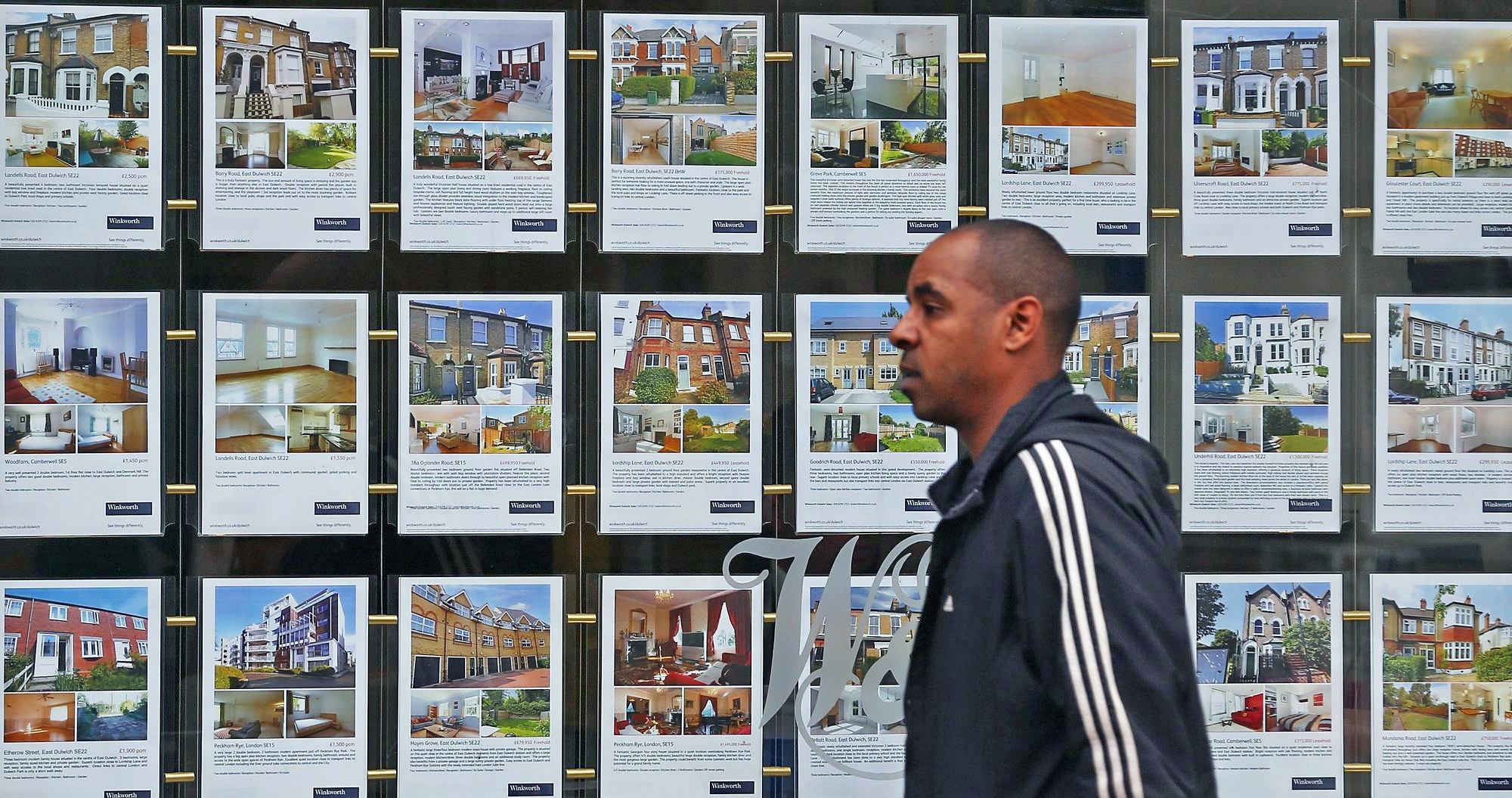

The most striking of these is the potential mortgage crisis. Mortgage interest rates have seen some of their most rapid increases in history. Current forecasts suggest that the rate on the best fixed rate two-year mortgage will be around 6% by the end of 2023. This has a lot of people worried, and rightly so.

Housing in the United Kingdom is extortionately expensive, especially for first-time buyers. The best way to measure this is with a house price to income ratio (HPI). The HPI shows how much the average British house costs relative to the average income earned in the country. Currently, house prices are roughly seven times earnings. This is up from around five times earnings in 2013 and way up from around three times earnings in the mid-1990s.

With house prices so high relative to income, people must borrow a lot relative to their income. This is only affordable for the average Briton due to the extremely low interest rates that we have seen in recent years. Now that these rates are rising, the game has changed dramatically and housing at current prices no longer looks remotely possible for many.

The OBR ignores this, however. In its forecasts, it argues that rising interest rates “have little net impact on aggregate” household disposable income because while “other interest costs rise […] higher interest rates also boost interest income on household savings”. This is laughable. The OBR are saying that because some people — mostly older savers — are earning higher interest rates on their savings, this offsets the huge income losses for borrowers as their mortgage payments increase.

However, borrowers are going to get squeezed hard. Non-political entities recognise this. Fitch Ratings, for example, has done some excellent estimates on how much 6% interest rates would cost mortgage borrowers. Fitch estimates that for a representative borrower earning a gross income of £50,000 a year with a loan-to-income ratio of 4.5x, a 2.5% mortgage refinanced to 6% would raise monthly mortgage payments from around £1,000 to £1,450.

After tax, a person on £50,000 a year receives an income of around £37,500 a year, or £3,125 a month. After their mortgage this person now has around £1,675 to spend, while before interest rate hikes they had roughly £2,125. At the same time, they are expected to pay higher energy costs and face the cost of goods rising at over 10% a year.

If the OBR cannot see that this situation is introducing a very high risk of a mortgage crisis, they should realise that the forecasting game isn’t for them.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe