Every saver knows that interest rates are freakishly low. In fact, they’ve been on the floor for more than a decade now. But is this just a weird anomaly?

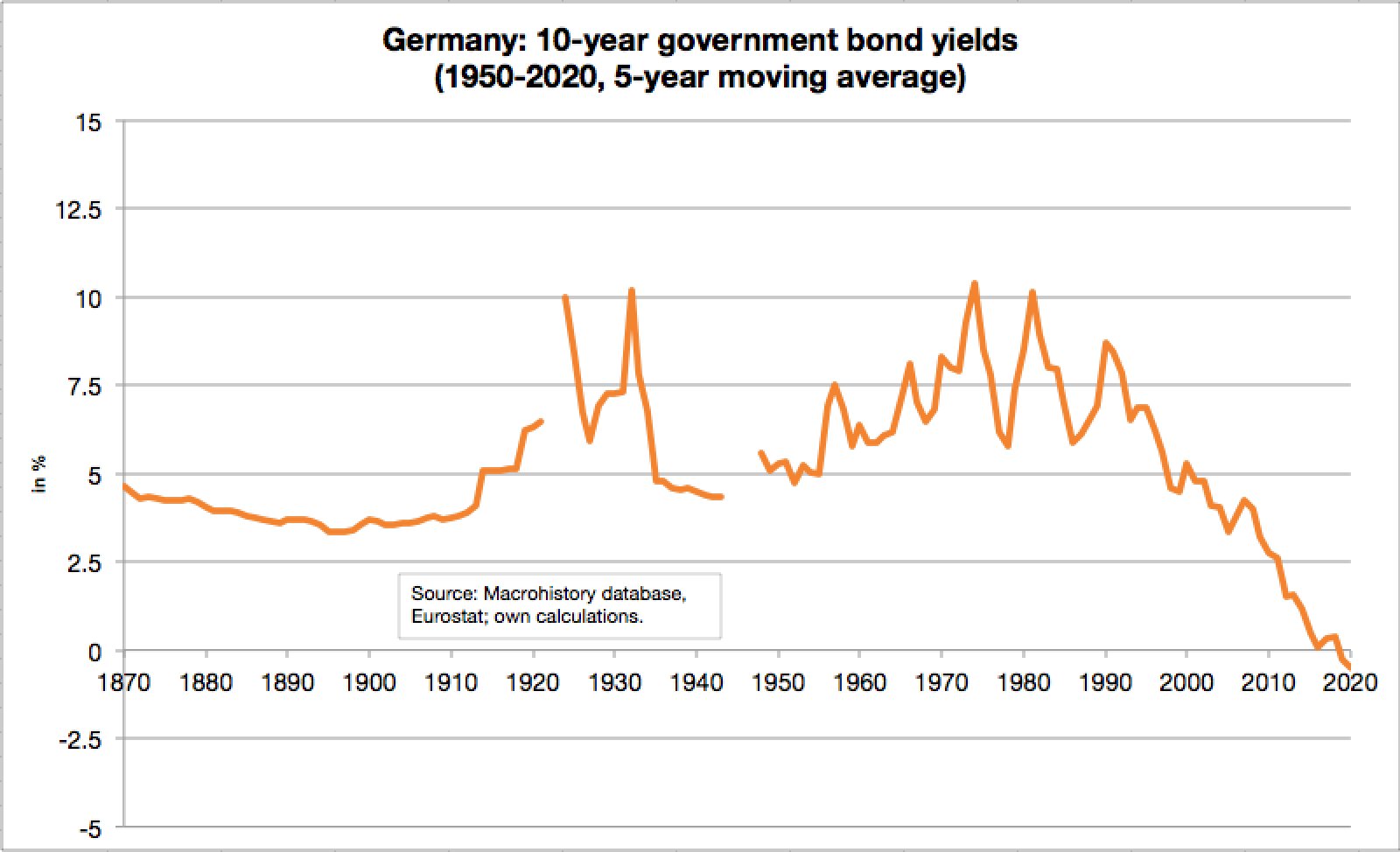

A chart tweeted out today by the economist Philipp Heimberger would suggest not. It shows the long-term trend in German interest rates (on government debt) over the last 150 years:

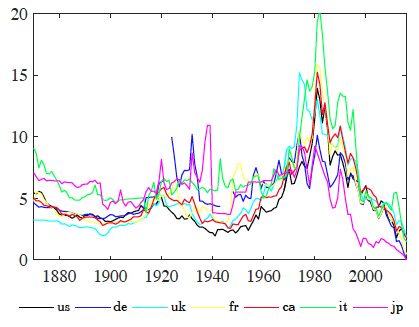

The most important trend is the remarkably steady fall over the last 30 years. Much the same has happened in all the G7 economies — as the following chart shows:

It’s tempting to blame this phenomenon on the series of unfortunate events that began with the banking crisis of 2008. But it’s now plain to see that the long collapse of interest rates started well before any of that.

The global disruption caused by the pandemic is the final test. If there’s no return to inflation (plus interest rate rises) then we’ll need to accept that we’ve entered a new era — one with permanently low rates.

This will have profound consequences. In fact, we’re already seeing signs of a shockingly new economic order. For instance, in Denmark, borrowers can now get a zero per cent mortgage. Just to be clear, this doesn’t mean a no deposit mortgage, it means that the borrower pays zero per cent interest. Furthermore, that’s fixed for 20 years — which demonstrates a sincere belief on the part of the lender that the new normal is here to stay.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeI think this is a very dangerous assumption to make, based upon historic data as it is. The Equitable Life failed because it thought high interest rates were here to stay; they weren’t. Property funds in Ireland rocketed when it joined the EU and enjoyed lower interest rates for a time, allowing people to borrow and speculate on property. It all ended in tears. As Bertie Wooster put it “I’m not absolutely certain of my facts, but I rather fancy it’s Shakespeare who says that it’s always just when a fellow is feeling particularly braced with things in general that Fate sneaks up behind him with the bit of lead piping.”

Any PG Wodehouse quote deserves an up vote, more so if it includes Bertie. PG can be used to explain all human existence if you dig deep enough into his wisdom. Just Blandings Castle can cover 90% of all human questions.

The trouble with the nil inflation / nil rates combination is that unlike in the past your debt’s real cost is not inflated away over time. So your mortgage will no longer be crippling for the first few years and then gradually ease as it’s eroded by inflation. It will be crippling for the whole term as every £ has to be paid back at its full value.

In the long term this has to be bearish for house prices.

Yes, interest rates at zero is likely to be a bit of a zero sum game for home buyers, as wonderful as it may seem at first. Mortgages may get harder to get, partly as less capital will get loaned out (why put capital at risk for zero return when it could be invested elsewhere?) and partly as the bar which is set for whether a borrower can afford the mortgage will get higher – interest rates at zero mean pay rises at close to zero. As you say, no lender can assume any more that the mortgage loan will get easier to pay off over time. The logical result is that lending volumes will fall, and that will indeed be bearish for house prices.

Agree completely with your analysis. The question for me is then how long this takes to feed into market prices. At the moment it feels like we are Wile E Coyote in those Road Runner cartoons. He runs off the cliff into thin air, and he keeps running quite happily until he notices. Then he stops, and looks dismayed….and only then does he plummet to the ground.

Houses same thing.

I’m struggling here – surely 0% mortgage rates where there is limited housing stock must result in absurdly bullish house-price inflation ….

Won’t any fundementally important – and rationed – item take on an infinite price 🤔

Consumers will gamble (and be told) that there will be no uptick in the interest rate curve in the future ….

Yes, a zero interest rate means you pay less for your mortgage, which would lead you to offer more money for the house (pumping up prices) – that is definitely part of the dynamic here. My assumption though is that, although the mortgage may be cheaper, the amount that the bank will be willing to lend you will be lower, which means you can’t pay more for the house after all. The flaw in my logic is that as long as governments are happy to quantitatively ease billions into existence and essentially give that to the banks at no cost then those banks will probably be quite happy to lend it on and forever more inflate house prices…

Zero interest zero inflation, this is one breath from deflation. Very terrifying as deflation is the real horror.

‘The last thing we need now is public sector profligacy or private sector speculation.’

Well that’s what we’ve had for most if not all of my lifetime, and it’s not going to change.

That aside, this is an important article and a subject that UnHerd might like to explore in more depth. For a few years now the prevailing wisdom has been that we have low or zero inflation in essential such as food, clothing etc, but runaway inflation in assets such as property, shares, art, watches, vintage cars etc. This is based on the belief that ‘When interest rates are at zero, the value of assets is infinite’. However, I see that a few people below are suggesting that zero interest rates for years to come could put a cap on, or even reduce, property prices. Who knows?

You also have to factor in the endless printing of money. This will continue because it is the only way to fund the endless expansion of the state. Presumably, this lead to a further increase in the value of assets as money itself continues to lose all value.

Yes, you have nailed it. I for one think that zero interest rates should, all else being equal, cause a fall in the capital that institutions are willing to lend, and with that a fall in asset prices. But the reason I am almost certainly going to be wrong is because the government will quantitatively ease billions into existence and hand it to the banks. Some fraction of that QE may help support the productive economy, but most of it will get stuck in inflated asset prices where it won’t do much good.

This is an incredibly superficial blog post that basically amount to saying ‘graph goes down for 30 years WOW!’ and little else.

There doesn’t seem to be any actual analysis of why they have fallen the last 30 years except ‘2008 can’t explain it’.

Seems to ignore actually analyzing factors like:

– persistent low inflation

– Quantitative Easing since 2008 – it’s interesting that UNTIL 2008 the interest rate was hovering around where the average for interest rates before the great economic crises of the 20’s and 70’s

– huge pool of new savings from high-propensity to save countries in the Far East

– Slower growth and demand for capital investment

– More capital investment taking place outside traditional banking in venture capital, hedge funds or dark pool capital sources

– Non-physical industries with less capital requirements

– Less competitive economy as slow monopolisation has occurred in many industries raising barriers to entry thus demand for capital

Maybe the authors should actually try to produce something useful, but I guess the clickbait model of news that now obtains militates against that.

Might increased longevity have something to do with it? The time value of money is bound to decrease when you have a few more decades of expected life compared to, say, 1900.

I have a question about these no interest mortgages in Denmark. Unless the Danish government promises some benefit, or it penalizes for non-compliance with its dictate to lend to home buyers, why would any bank or other lending institution grant these loans? There doesn’t seem to be any gain for them. Indeed, given that the principal still has to be paid off, the chance of default still exists, and that would be a loss for the institution. I just can’t grasp how that would work, barring governmental actions such as those described above.

” The last thing we need now is public sector profligacy or private sector speculation.”

Indeed, the low rates merely provide politicians an excuse to waste more of the public’s money. What is the time value of money in a zero interest world?

Interesting point. Presumably it’s unaltered?

In the past, you could borrow £10,000 over 25 years and repay it at £50 a month. Out of your annual income of say £3,000 to begin with, you’re initially spending 20% a year on the mortgage.

By year 25 your income has inflated to £30,000, but the instalments are the same. So you’re now spending only 2% to service it.

If instead there’s no inflation of your salary, then you’ll be paying it back at full original value throughout, no?

So if you were borrowing to buy a house, rather than paying £10,000 which will be on average 11% of your income over the term, maybe instead you only pay £5,500. In a nil-interest world, that is also going to be 11% of your income.

Of course it also implies a gradual, secular 45% correction in house prices.

If one is to go along with fatuous extrapolation of trend lines, surely the conclusion from this chart is that interest rates will become increasingly negative, not that they will stay at zero.

Excellent point, till having debt becomes Income! WOW!

Might it be that the trend over the past 150 years has always been downward to only slightly above 0% with the peak years being aberrations due to depression and recovery from WWI (1930s) and recovery from WWII?

I’ve begun to think that modern politicians and economists do not understand what worldwide shocks those events were and how the recoveries were unique events, not the norm. One reason for that frame of mind being that their data is, at best, only ~150 years old.

When politicians think an aberration is the norm, all kinds of bad things can happen by trying to establish or maintain an aberration when the conditions that generated it are long past.

There is data (of sorts, extrapolated from ancient records) going back 5,000 years to Babylonian times. We are now “enjoying” the lowest interest rates, essentially, since money was developed.

Not sure what the significance of that is; interesting times!

UnHerd really need to get someone with some decent knowledge on finance as it is so important. Perhaps look at some of the bloggers included on Zero Hedge for smart thinkers to aproach. If you are just going to regurgitate mainstream/govt nonsense then don’t bother. Seems to me only the “gold is money” people have a handle on the financial wheels moving behind pretty much everything that is happening.

The graph that is missing is the astronomical global debt rise. Led by the US Federal Reserve the world has accumulated trillions of debt – beyond anything ever experienced before – on which we have lived beyond our means and now are using to stimulate our fake economies.

Which means the other trick for stimulating economies – dropping interest rates – is no longer available because we are at 0%. And raising rates means govts would not be able to afford to pay interest on their OWN borrowings. And those borrowings/bonds/Treasuries etc are mostly owned by global banks, other countries like China, peoples pension funds etc. So they can’t go up and they can’t go down ‘cos 0%

Japan has survived this dilemma as they have patriotic savers to buy their own debt and an export ecomony to live on. China just prints its own funny money without borrowing but has its export trade to bring in other currencies cash to offset the effect of that. And gold.

And Russia has practically no debt and a small welfare state in order to live within their means. And LOADS of gold for when all fiat currencies go pop.

I highly recommend the very watchable series Hidden Secrets of Money by Mike Maloney on YouTube – a series that started our education into what the hell is actually going on and an insight into what he calls “the greatest ever transfer of wealth” that is coming. The mechanisms underpinning our world are quite uncanny, you really won’t believe it…

Thanks, it’s a shame that even a site such as unherd publishes so much tosh from authors who just happen to be academics/”intellectuals” while so many of the mere comments are so much more worthy to be an article.

Thanks Robin! When we started learning about finance via that Mike Maloney series it was an absolute revelation and suddenly bonkers stuff in the world makes sense. The financial system is the knowledge they REALLY don’t want us to have 😉

Gold is not money. It is a commodity.

You desperately need to learn about what the archeological record tells us about the origins, purpose and operations of money, and the last place you will find that is among the “gold-buggery” rampant at a place like Zero Hedge.

The work of The International Scholars Conference on Ancient Near Eastern Economies is a good, credible place to begin.

Lets take another look at this, from a different perspective-is money evidence of debt? It used to be called a ”promissory note”-I promise to pay the bearer xxx. So, if you have $20 in your pocket that means that someone, somewhere owes you something as the ‘money’ is a promissory note. I read, not sure if its true, that a bank having ”your” money in its account -it has to pay interest on that money to you-for looking after something that is already evidence of debt-its just not in your pocket, its in the bank. Put it this way..John has 1 chicken to sell and jane offers an exchange of firewood=barter. But one day john has 2 chickens to sell, but Jane has the same amount of firewood. John agrees to give the 2 chickens to Jane and she gives him a promissory note, promissing to ‘pay back” the deficit=the debt at some point unless she can pass in on, and on, and on……like the current of water=currency. Banks sit on the edge of the ”current” ‘on the bank’…get it! There is a wonderful website in Canada called Servant King by marcus-he explains money in detail. It worth a watch to really understand what money is. So, remember the next time you have $20 in your pocket-somebody owes you. But the middle man/woman is the bank. Here is another problem. Robbo

Correct — all fiat currencies are “promises to pay” by the sovereign. Private sector entities want to hold those promises (which we call dollars or pounds or whatever) as “savings” because they are needed to acquit the taxes, fees and fines levied by the government, which won’t accept anything else in payment.

All other debt instruments are valued based upon the credibility of the borrower’s “promise to pay” relative to the sovereign.

The “barter story” of the origin of money is fallacious and unsupported by the archeological record. Debts predate money. In fact, they predate writing, which itself sprung from the record keeping of temple complex debts in the Bronze Age civilizations of the Fertile Crescent.

“The Mesopotamian cuneiform script can be traced furthest back into prehistory to an eighth millennium BC counting system using clay tokens of multiple shapes. The development from tokens to script reveals that writing emerged from counting and accounting. Writing was used exclusively for accounting until the third millennium BC, when the Sumerian concern for the afterlife paved the way to literature by using writing for funerary inscriptions. The evolution from tokens to script also documents a steady progression in abstracting data, from one-to-one correspondence with three-dimensional tangible tokens, to two-dimensional pictures, the invention of abstract numbers and phonetic syllabic signs and finally, in the second millennium BC, the ultimate abstraction of sound and meaning with the representation of phonemes by the letters of the alphabet.” (from the University of Texas “The Evolution of Writing”)

Yes, this had been a trend for decades. My father spoke of a time where interest rates in South Africa was above 20%! Since the lowering of rates this has been in the back of my mind; “Should I buy a new home with these new interest rates?” Well, it all sounds good until the G7 economies goes into recession, and realise they need to push up interest rates significantly.

Luckily SA is still a few basis points away from 0% interest rates, and with the dollar devaluation in the next decade SA’s high debt might not be that much to pay off.

Why would recession cause rates to rise?

Hasn’t it historically been the other way about – the rate rises triggered the recession?

IMO they feed on each other. In a recession money moves to safe investments (gilts); and with increased risk interest rates go up. Everyone struggles to borrow money, resulting in reduced spending, less economic activity.

Usually inflation is also part of this merry dance, but ultimately it affects both cost-of-things and income.

I had just started work in the time that Tiaan is talking about. All my income went on mortgage payments, but with inflation-driven annual salary increases it soon became more affordable.

And when time came to sell the Rand value of the house had itself increased with inflation.

From that experience – you do need to be in a position to survive a surprise increase in interest rate – e.g. due to a G7 recession – but if you can, everything should cancel out after a couple of years.

Aunties advice – assume you will sell the house you buy to a South African (in Rand) and don’t think about the dollar and SA debt …

The trend in interest rates since 1980 is in an inverse relationship with the rising energy cost of energy.

https://surplusenergyeconom…

I’m assuming the rising energy cost of energy is having a significant dampening effect on inflation which is only mitigated by debt and monetary stimulus programmes.

I really like this Finnish guy Tuomas Malinen as he writes about global finance in a way that is both expert but with as little jargon as possible. He explains likely scenarios from here as the Great Reset unfolds and explains a phenomenon discussed in an FT article recently called “Gosbankification” Fascinating short read…

“[“¦] the balance sheets of major central banks would

turn into investment vehicles with limitless boundaries. Central bankers

would decide which countries and corporations would survive. They would

effectively metastasize into Gosbanks (the central bank of the

now-defunct Soviet Union, responsible for central planning) of the

world.”

https://gnseconomics.com/20…

It’s the job of our democratically elected representatives to use the political process to guide fiscal policy in a way that is productive and beneficial to the citizenry. For too long now they have abdicated that responsibility to monetary policy and their central bank technocrats.

Now that the zero-lower bound is here, the gig is up. The fiscal nettle will have to be grasped, or further undemocratic central bank exotica will continue to flourish for the benefit of the oligarchs and at the expense of the working man and woman.

True, the first thing that comes to my mind if offered a zero percent loan for 20 years?

Fill the wheelbarrow and head to the stock market. With a 20 year time horizon, a big free win is all but guaranteed.

If I were a politician, I’d back up the truck. Send money to any demographic, voting block that was on the edge to get their vote. Then send them more. I would be in power forever.

Aside from the fact that my stock market record is terrible, I suspect this is not going to end well.