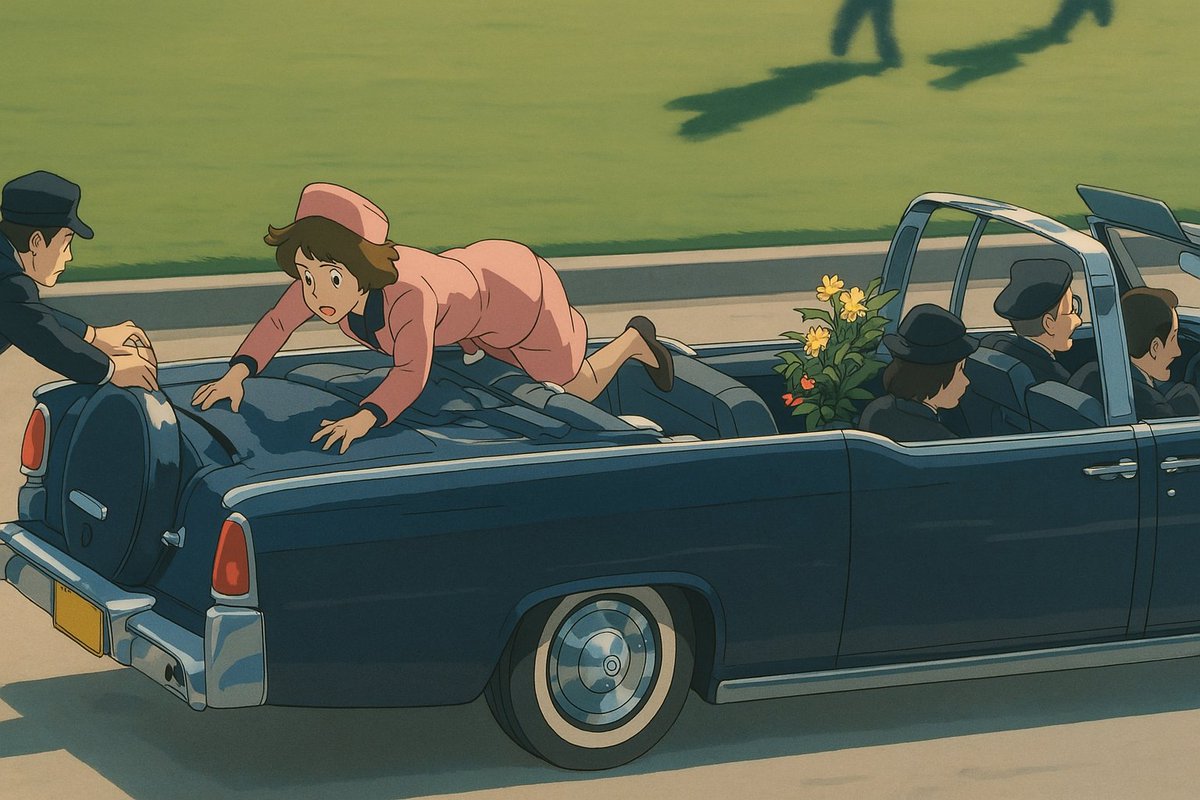

For much of this week, X has been filled with eerily familiar yet undeniably off-putting images that represent a new frontier in AI’s consumption of human art. Users have discovered that ChatGPT’s latest update allows them to transform any photograph into something resembling a scene from a Studio Ghibli film. Within hours, the internet was awash with these uncanny renderings — everything from 9/11 and the Kennedy assassination to Pennsylvania treasurer R. Budd Dwyer’s televised suicide, all reimagined in the distinctive style of Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki. This is more than just a passing trend, though. Instead, it’s another milestone in AI’s ongoing appropriation of human artistic expression.

First came the novelty of seeing serious historical events transformed into whimsical anime pastiches. Then came the rush to feed every conceivable meme template into the algorithmic maw. By Wednesday, Elon Musk was participating, a sure sign that whatever subcultural cache the trend might have briefly possessed had evaporated entirely.

There’s something particularly depressing about Miyazaki’s aesthetic becoming the unwitting template for this mass AI experimentation. The 83-year-old animator’s meticulously crafted style — the product of thousands of hours of human labour — has been crudely approximated by the very technology he so openly disdains. In a 2016 demonstration that has resurfaced amid this trend, Miyazaki watched AI researchers present a grotesque digital creature that moved by dragging its head along the ground. His response was unequivocal: “I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.” He continued: “I feel like we are nearing the end of times. We humans are losing faith in ourselves.”

Nine years later, Miyazaki’s words seem almost prophetic. What is this flood of AI-generated Ghibli knockoffs if not a collective surrender of our artistic sovereignty? The modern internet user, bombarded by an endless stream of content, has outsourced even the act of image manipulation — once a legitimate form of digital folk art — to machines. The lazy shortcut of asking AI to simply “make it look like Ghibli” replaces genuine creative expression with the press of a button.

This hollowness points to a deeper artistic crisis. Human-created memes, at their best, represent a legitimate art form that emerges organically from distinctive individual sensibilities. Consider Donald Trump, whose idiosyncratic communication style spawned endless memorable memes which helped propel him to political prominence. From “covfefe” to “nipples protruding […] very very disrespectful” to “very fine people”, Trump’s linguistic peculiarities created genuinely novel cultural moments that resonated far beyond their immediate context. These weren’t just jokes but authentic cultural artefacts, carrying the unmistakable signature of individual creativity that AI cannot replicate.

The Studio Ghibli meme trend, however, constitutes the further “ensloppification” of internet culture. When anyone can generate unlimited variations of the same basic template with minimal effort, we’re left with an undifferentiated mass of content — or “slop”, to use the increasingly common internet parlance.

The speed with which the Ghibli AI cycle played out illustrates this perfectly. What might once have been a week-long trend with distinct phases of adoption, refinement, and eventually ironic meta-commentary was compressed into less than a day. By the time average users became aware of the phenomenon, it was already being declared “over” by those at the cutting edge. And unlike organic memes that might experience revivals or evolve into new forms, this AI-generated trend will likely never resurface except as a footnote in some future digital archaeologist’s catalogue of fleeting 2025 phenomena.

Musk’s involvement sealed the trend’s fate. When platform owners participate in meme culture, they strip away any remaining countercultural energy. Throughout his tenure at X, Musk has functioned as a one-man validation system for content that catches his eye, transforming niche humour into broadly accessible but quickly exhausted cultural products. His participation marks the moment a trend officially becomes mainstream — and thus instantly passé.

Yet the larger pattern represented by the Ghibli trend — the algorithmic consumption of human art, the devaluation of artistic labour, and the surrender of creative agency to machines — continues unabated. The real tragedy isn’t just that AI can now imitate Miyazaki’s style, but that we increasingly seem content to let algorithms replace the human artistic impulse entirely. When we surrender art to automation, we lose not just the distinctive voices of individual creators but also our collective power for creative expression.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe