On May 6th 1997, then Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown sent a letter to the Governor of the Bank of England. In the letter Brown highlighted the New Labour manifesto commitment to “ensure that decision-making on monetary policy is more effective, open, accountable and free from short-term political manipulation”. In 1998, this new decision-making framework was brought into law under the Bank of England Act 1998.

These legal developments reflected broader changes in the discipline of economics. As inflation subsided in the 1990s, many attributed this new stability to central bank policy. It seemed that many central banks had cracked the code of setting interest rates to ensure healthy economic growth without disruptive price rises. Brown, and other politicians like him, believed that public policy could be set in line with economic science and so he gave free rein to the experts.

The experts really believed that they had cracked the code. In 1993 the monetary economist John B. Taylor published a paper with an equation that many assumed allowed central banks to set policy along scientific lines. The equation became known as the ‘Taylor Rule’. It measured the current rate of inflation and compared it to the economy’s potential for further growth. So, if inflation was high or the economy was running too hot, the rule advocated higher interest rates. If inflation was low or economic growth was sagging, it advocated lower rates.

While central bankers did not follow the Taylor Rule to the letter, it has nevertheless been a golden rule central bank policymaking since. That is, until recently. The chart below shows the Taylor Rule for the United States compared with the Federal Reserve’s interest rate. While the Federal Reserve’s interest rate has closely followed the Taylor Rule most of the time since the start of 2021 the two have diverged sharply.

Why is this? For the most part it is because we are seeing a combination of sluggish economic growth and high inflation. That means that the Taylor Rule is telling central bankers to raise interest rates sharply, but the central bankers are looking at the poor economic growth and are reluctant to raise rates. They are also eyeing up the overextended financial markets worrying that if they raise rates the speculative excesses that have been encouraged by low interest rates will collapse.

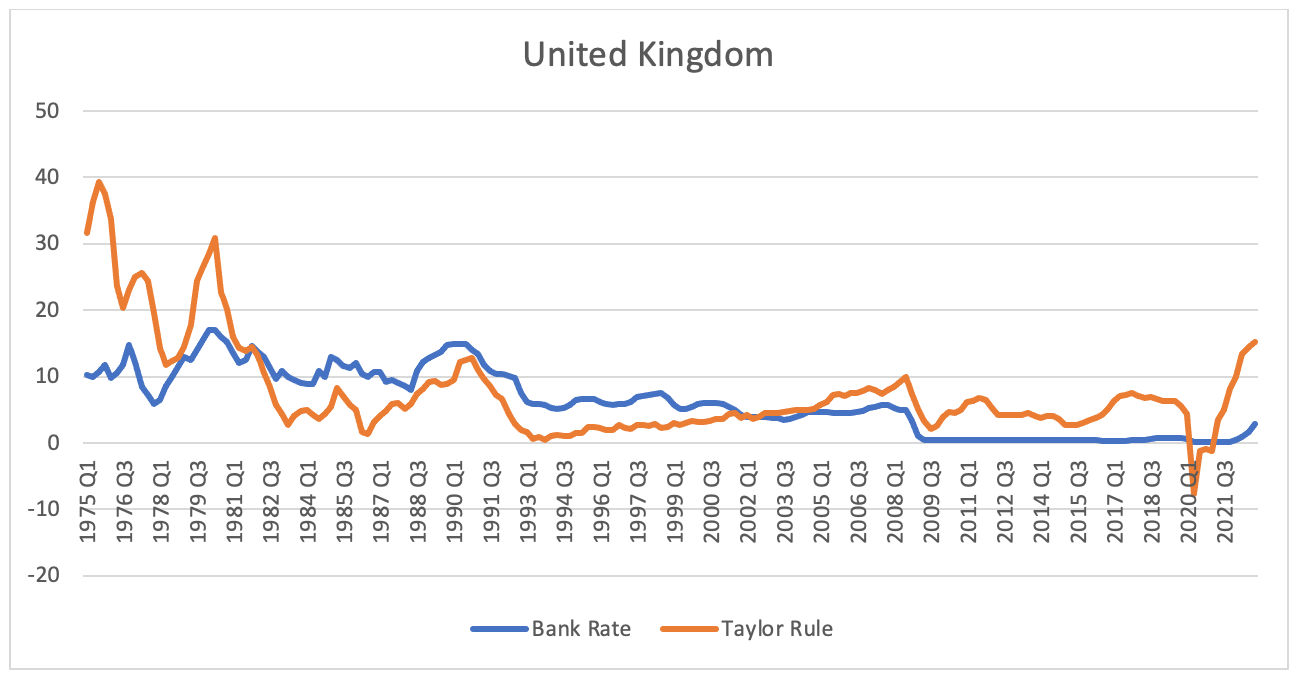

What about in Britain? As the chart below shows, the Taylor Rule has never worked as well in Britain as in the United States. There are a lot of reasons for this, but perhaps the primary one is that during this time the British economy has been in a state of decline. This decline has meant that inflationary pressures have been much more persistent in Britain than in the United States. Policymakers have therefore sought to moderate their use of using interest rate policy to steer the economy and instead have used it to promote financial stability and especially stability of sterling.

Nevertheless, as in the United States, since the start of 2021 the Taylor Rule has been screaming for the Bank of England to raise rates, but the bank has refused. If British central bankers followed the Rule, we would current have interest rates of over 15% rather than the 4% rates we currently see. So, as in the United States, central bankers are seeing a failure of their ‘scientific’ methods for setting interest rates in the face of economic dysfunction and stagnation.

Where does this leave us? Unless something changes soon, it looks like the Taylor Rule is heading for the dustbin of history. Unless the inflation and stagnation rapidly subsides — in which case economists can chalk this unusual period up to a blip — the scientific pretensions of central bankers will no longer be very convincing. In that case, we will be entering a world of monetary policy uncertainty.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeThe hubris of those that think they have ‘cracked the code’ never ceases to amaze, same (or similar) jokers to the spreadsheet doctors who locked us down with ‘I know best’ and dodgy data.

But the article gives the game away with the phrase ‘worrying that if they raise rates the speculative excesses that have been encouraged by low interest rates will collapse.’

Hoist by their own petard they cant back out of the hole they have dug with QE

yes but how do WE survive the fallout – silver or gold coins ??

yes but how do WE survive the fallout – silver or gold coins ??

The hubris of those that think they have ‘cracked the code’ never ceases to amaze, same (or similar) jokers to the spreadsheet doctors who locked us down with ‘I know best’ and dodgy data.

But the article gives the game away with the phrase ‘worrying that if they raise rates the speculative excesses that have been encouraged by low interest rates will collapse.’

Hoist by their own petard they cant back out of the hole they have dug with QE

Did they accidentally reverse the colours on the US chart? The Federal Funds Rate is not over 10%.

Indeed. The comment below that chart does not make sense unless the colours have been reversed.

The 400 PhD economists employed by the Fed are about as much use as a fridge to an eskimo. These people think they can control an increasingly complex and globally interconnected economy with a single blunt instrument……short-term interest rates. It’s perfectly obvious none of them have ever had a real job outside academia or the DC bubble…..running a business for example.

Having created runaway inflation by their biblical money printing over the last decade, they now want us to believe they can put the genie back in the bottle by tweaking a single interest rate. Arsonists posing as firemen.

Indeed. The comment below that chart does not make sense unless the colours have been reversed.

The 400 PhD economists employed by the Fed are about as much use as a fridge to an eskimo. These people think they can control an increasingly complex and globally interconnected economy with a single blunt instrument……short-term interest rates. It’s perfectly obvious none of them have ever had a real job outside academia or the DC bubble…..running a business for example.

Having created runaway inflation by their biblical money printing over the last decade, they now want us to believe they can put the genie back in the bottle by tweaking a single interest rate. Arsonists posing as firemen.

Did they accidentally reverse the colours on the US chart? The Federal Funds Rate is not over 10%.

Yes indeed. It is a casino with under the table levers gone rusty.

Yes indeed. It is a casino with under the table levers gone rusty.

The graph for the US seems to be contradicted by the text in the paragraph below it.

The graph for the US seems to be contradicted by the text in the paragraph below it.

I don’t understand much of the commentary in this article. If the Taylor rule was only invented in 1993, it seems odd to retro-fit it to the 1970’s (UK chart) and 1950’s (US chart)? What is that supposed to tell us? Since 1993 it seems to have worked broadly equally well for both countries. Has the UK been in decline since 1993? Have inflationary pressures been significant since then up until this year? And surely the UK government stopped using interest rates as a tool of exchange rate policy after September 1992.

I don’t understand much of the commentary in this article. If the Taylor rule was only invented in 1993, it seems odd to retro-fit it to the 1970’s (UK chart) and 1950’s (US chart)? What is that supposed to tell us? Since 1993 it seems to have worked broadly equally well for both countries. Has the UK been in decline since 1993? Have inflationary pressures been significant since then up until this year? And surely the UK government stopped using interest rates as a tool of exchange rate policy after September 1992.

The problem with the Taylor Rule is that the potential future growth rate is a subjective judgement. Gordon Brown justified increasing government expenditure year after year by claiming that Britain was persistently at the bottom of the economic cycle and that growth was set to be strong.

The other problem is that the last three decades have been characterised by transferring production to low income countries in the developing world with low inflation as the result.

What Britain´s potential growth rate at a time of falling house prices and collapsing financial institutions is anyone´s guess.

The problem with the Taylor Rule is that the potential future growth rate is a subjective judgement. Gordon Brown justified increasing government expenditure year after year by claiming that Britain was persistently at the bottom of the economic cycle and that growth was set to be strong.

The other problem is that the last three decades have been characterised by transferring production to low income countries in the developing world with low inflation as the result.

What Britain´s potential growth rate at a time of falling house prices and collapsing financial institutions is anyone´s guess.