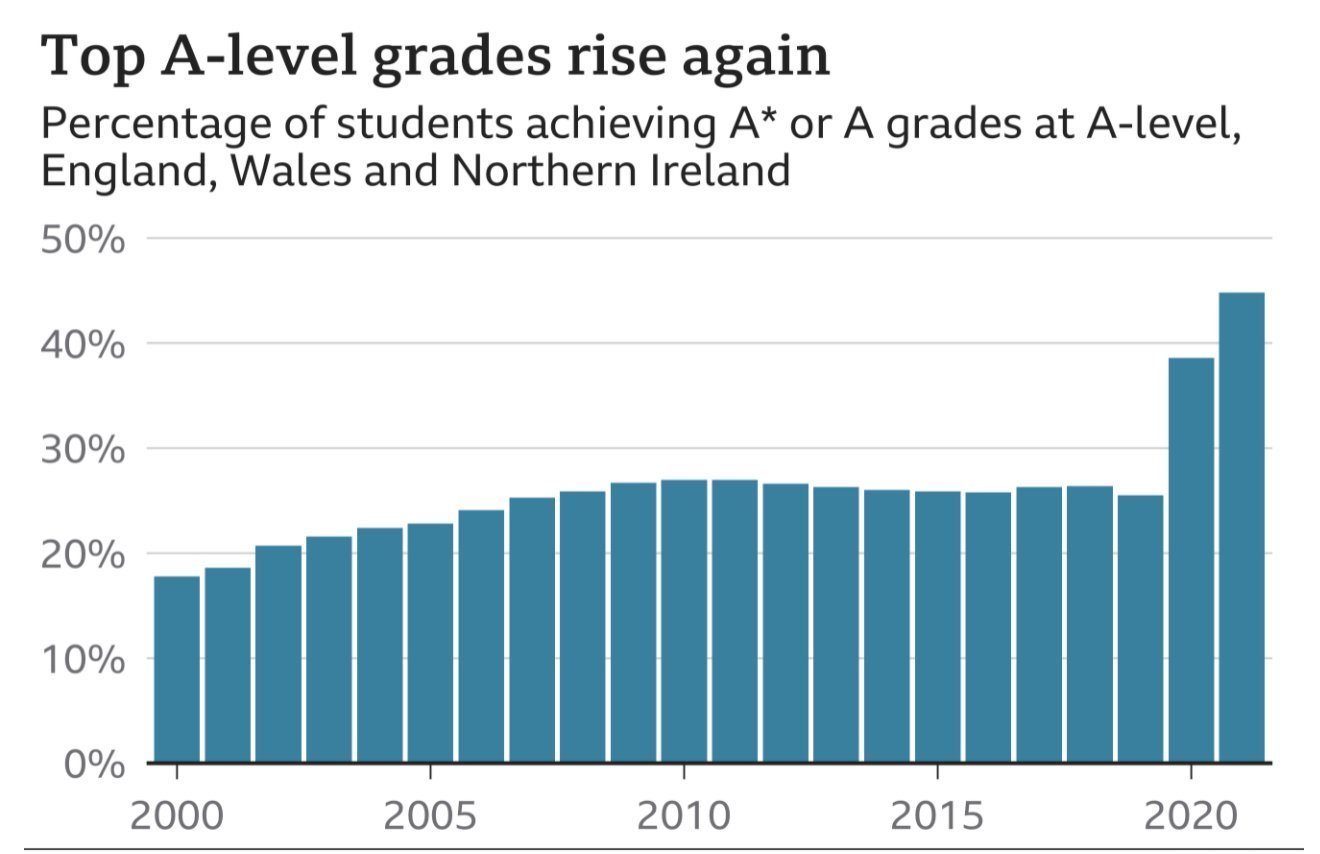

This week’s A level and GCSE results seem pretty scandalous, with dramatic grade inflation over lockdown seeing nearly half of students awarded the top A* and A grades. The results threaten public confidence in our examination system and will no doubt create some serious headaches for university admissions tutors.

But on reflection I think it’s the right outcome. Here’s why.

Grades for the past two years have been based on teacher assessments following the cancellation of exams.

In the best of times, exams are useful because they are objective, but they are never “fair”. As a former teacher, I can vouch for the fact that the best students do not always get the best grades; pressure, personal circumstances and even bad luck result in grades being dropped for a certain number of students. I myself turned up to my GCSE physics exam to find it was actually economics and I’d read the timetable wrong — a stupid mistake, but impossible to foresee in advance.

Statistically, over a large cohort of students, similar numbers will over- and underachieve each year. But these anomalies cannot be predicted at an individual level.

Teachers really are experts in seeing children’s potential. If asked to assess a student, they will award a grade that reflects the best of that pupil’s ability — which will in many instances be a more generous assessment than what would have been achieved in an external exam. It might be statistically certain that some students in each class will underperform their potential, but how can a teacher decide which students that will be? If no pupils are downgraded, the inevitable result is grade inflation.

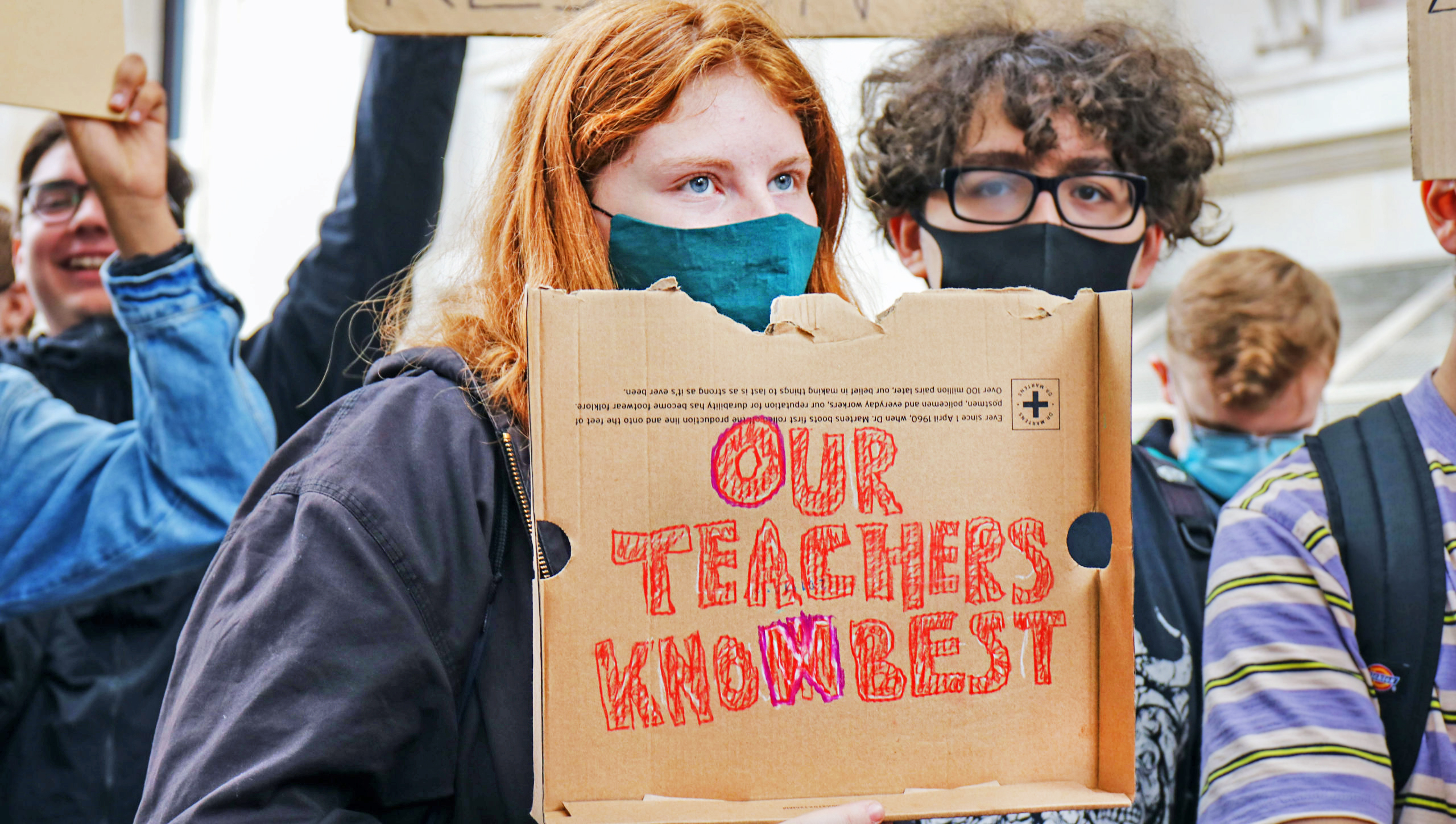

Last summer, Ofqual attempted to mitigate against the inflationary effect of Teacher Assessed Grades (TAGs) using a complex algorithm. The logic behind this was sound, but it was poorly executed and it was followed by a national outcry as heart-breaking individual stories emerged.

Of course there are many exam disasters every year, but you can’t leave it to a computer algorithm to assign the bad luck — it understandably seemed arbitrary and cruel. As a result, the code was abandoned and Ofqual opted for straightforward TAGs this year.

The situation is far from ideal, but given the school closures and exam cancellations I personally can’t see an alternative. We have forced our young people to bear an almost unimaginable cost during the pandemic, and we can’t ask them to sacrifice any more. If that means one-off grade inflation then so be it.

Miriam Cates is MP for Penistone and Stockbridge

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe