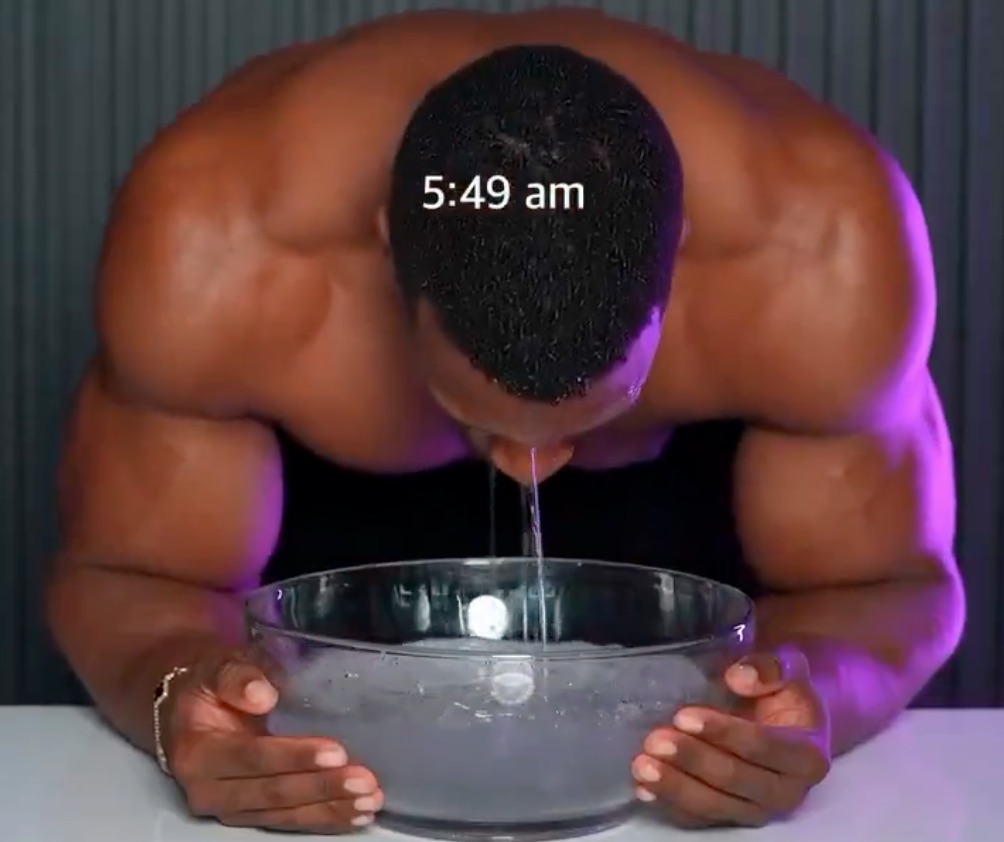

In a recent viral video, influencer Ashton Hall (though far from a household name, he has almost three million YouTube subscribers) documented his five-and-a-half-hour “morning routine”. It begins at what we can only imagine was the Andrew Huberman-inspired start time of 3:52 am. What follows is a hyper-curated montage of self-care rituals and pseudo-productivity hacks: pre-dawn squatting in his kitchen, meditative hot-tubbing, and — for whatever reason — rubbing a banana on his face. Most scenes feature a bottle of Saratoga Springs water. It’s like Hall read — no, watched — the morning routine in American Psycho and asked himself: “How can I make this more on the nose?”

On one level, Hall’s video drives home an annoying quality of social media. Today, everything is advertising in the most literal sense. Your hot takes and 30-second clips will inevitably be punctuated by ads for Halara leggings, Crumbl cookies, Chili’s, and now Saratoga Springs water. The video was rightly mocked, in the same way we might mock a cringeworthy ad spot. Everyone offered their own spin, from the Asian version to the SoundCloud rapper version. Yet beneath the mockery lies a cultural shift, one that’s been mounting for decades and now feels beyond parody. Contemporary masculinity is packaged, commodified, and sold back to men through an aestheticised lens once primarily reserved for women.

In The Beauty Myth, the American author Naomi Wolf warned that unattainable beauty standards trap women in cycles of anxiety and consumerism, a critique so familiar that it now feels almost like a truism. We live in a world in which consumption seeps into every facet of identity. Those same pressures, once recognized predominantly as targeting women, also shape masculinity. Behaviors previously dismissed as “metrosexual”, a term popularized in the Nineties for men openly invested in grooming and appearance, or even labelled “gay”, have become mainstream, algorithmically promoted, and fully normalized. Behind almost every contemporary “health trend”, from weightlifting and mewing to optimizing nocturnal tumescence in the style of Bryan Johnson, is the promise that perfection — and now, even immortality — is available for purchase.

Susan Bordo, in her influential work The Male Body, chronicled the evolution of masculinity from being culturally invisible, with men traditionally cast as observers rather than the observed, to becoming highly visible objects of aesthetic scrutiny. Bordo noted a pivotal shift in late-20th-century media, beginning with provocative commercials such as Calvin Klein’s iconic billboards, which were the first mainstream advertisements to objectify the male form both openly and in a sexually charged way. These ads not only invited admiration but normalized male bodies as objects of desire outside of an explicitly homosexual context. Hollywood soon followed advertising, showcasing male bodies as idealized, muscular and camera-ready, further solidifying a new standard for masculinity.

Just as women have long been targeted by unrealistic beauty standards, men are now similarly bombarded with ideals that cause body dysmorphia, including increased rates of cosmetic surgery. A rising number of young men are reporting the anxieties long familiar to women, dissatisfaction with their appearance chief among them. This is not about vanity, as some may claim. Instead, it’s that everything in our lives is a product to be commodified.

The absurdity of Hall’s “morning routine”, while easily mocked, nonetheless reveals a promise, especially to the people who can’t see through its charade. And, frankly, that’s most young men. Ashton Hall’s “morning” suggests that through disciplined consumption, men can optimize their entire lives. Of course, this promise is hollow. The commodification of identity ultimately traps people in an endless cycle of dissatisfaction.

Hall’s outwardly harmless, if extremely goofy, “self-care rituals” are symptoms of a broader cultural malaise. And nobody described that malaise better than Bret Easton Ellis in American Psycho: “There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory. And though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable, I simply am not there.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe