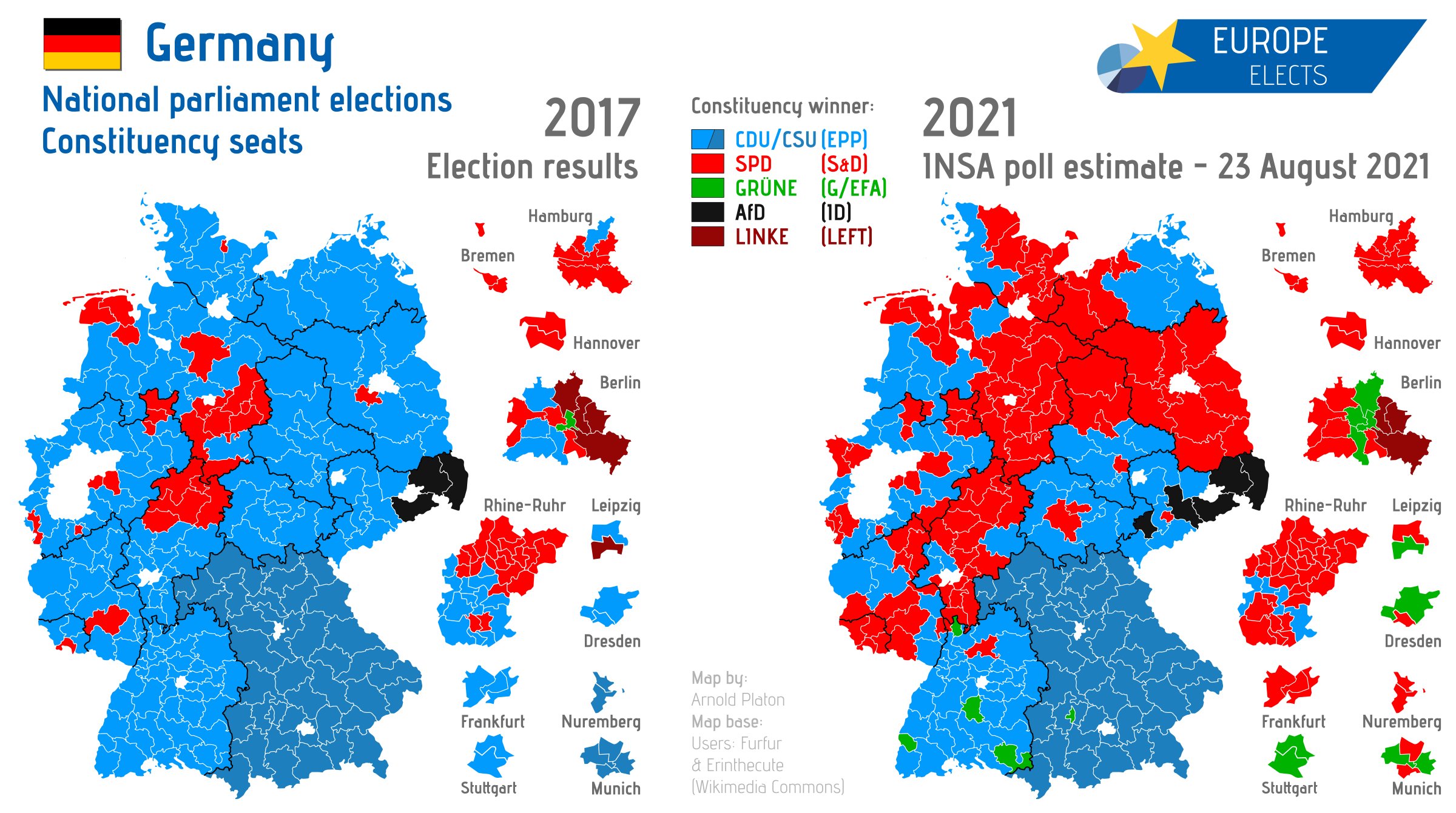

Are centre-Left politics on the rise again in Germany? It certainly looks that way. The latest polls suggest that the Social Democratic Party (SPD) could more than double its constituency seats in the upcoming elections. It’s also the first time since 2017 that the German Social Democrats have not trailed behind Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats in the polls. At 23% each, the two parties are neck-and-neck.

Momentum is in the SPD’s favour. Since February, the reigning coalition have fallen by 13 points in the polls while the Social Democrats have gained 8. Their chancellor candidate, Olaf Scholz, is now far and away the most popular option for German voters. As things stand, he may even lead the negotiations to form a coalition for post-Merkel Germany.

But we should be careful about reading too much into Scholz’s popularity.

For starters, Merkel herself still ranks consistently as the most popular politician, well ahead of the SPD leader. In second place is Markus Söder, the Bavarian Minister President who rivalled Armin Laschet for the chancellor candidacy but lost.

This gives a more accurate picture of what is causing the rise in SPD fortunes. When Olaf Scholz was first announced as the party’s candidate for the chancellorship last year, his party trailed nearly 20 points behind Merkel’s CDU and polling indicated that this gap would have widened further had the Christian Democrats nominated Söder. But they did not and went for the hugely unpopular Laschet instead. The more voters see of Laschet, the less they like him, and it increasingly appears that the CDU will pay a heavy price for dismissing their voters’ views.

While often described as one of the two “people’s parties”, the SPD have only managed to field their candidates as German chancellor three times in the country’s post-war history. Willy Brandt (1969 to 1974) was an affable man who had fought passionately for the rights of West Berliners in his time as mayor of the city. His successor Helmut Schmidt (1974 to 1982) still ranks as one of Germany’s most popular chancellors ever. Even Gerhard Schröder’s scandal-ridden tenure from 1998 to 2005 survived the 2002 election thanks to his personal charisma.

What the success of these three men highlights is the dependence the SPD has on the popularity of its leaders, rather than any enthusiasm for the party and its platform. That’s because, since the end of the Second World War, the party has been suffering from an identity crisis. Their first post-war leader Kurt Schumacher, while opposed to communism, was still a dyed-in-the-wool Leftist who pulled the newly reformed party away from the centre and had little to offer in the face of the economic miracle that accompanied his rival Adenauer’s tenure.

When the party officially abandoned the establishment of socialism as a key aim, it was not entirely certain what to replace it with. There was clearly an appetite for social reform and more progressive politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s, years during which the two SPD chancellors were able to make a strong impact.

But Schmidt in particular had a reputation for being a political pragmatist rather than an ideologue, something that successive SPD leadership teams have found hard to replicate. His party has since struggled to find a place for itself wedged between the far-Left party Die Linke and a CDU which has become increasingly centrist.

It remains to be seen if Olaf Scholz has the same talent for charming voters as his predecessors. His popularity is still dependent on being the least worst option rather than the people’s first choice. That is always a dangerous strategy. If the CDU switches to a more popular candidate or Laschet develops a more compelling message than ‘don’t vote for the Left’, the SPD’s popularity might sink as quickly as it has risen.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe