Jeff Bezos of Amazon Credit: Patrick Fallon/ZUMA Wire/PA Images

Innovation, disruption, competition, markets, capitalism – the mantra of Silicon Valley. Except, of course, when it’s not.

Because once a start-up starts up, the very last thing it wants to have to do is compete, face markets, and meet the challenge of innovation. It wants to rise rapidly to dominance, destroy competitors, and quash any innovative and potentially disruptive upstarts. A rising star company is as interested in market capitalism as Lenin. If you doubt me, ask Zuckerberg (Facebook), or Page and Brin (Google), or Bezos (Amazon); although, of course, you might not get a candid response.

If you want a straight answer, go to Peter Thiel, venture capitalist-cum-entrepreneur, co-founder of PayPal, and Facebook’s first outside investor. Not to mention always worth listening to, as he speaks his mind. “Competition is for losers,” he wrote in the Wall Street Journal [1. Peter Thiel, in the Wall Street Journal for September 12, 2014: “Competition Is for Losers: If you want to create and capture lasting value, look to build a monopoly.” https://www.wsj.com/articles/peter-thiel-competition-is-for-losers-1410535536.]. Every company should aspire to become a monopoly. Monopolies are good things.

The monopoly conundrum

Of course, monopolies are nothing new, and governments since at least the days of Roman Emperor Justinian have been pushing back[2. Sir Edward Coke writes in his judgment in “the Case of Monopolies” “For we read in Justinian that monopolies are not to be meddled with, because they do not conduce to the benefit of the common weal but to its ruin and damage.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darcy_v_Allein.].

Sometimes they’ve taken advantage of cosy relationships with business favourites; sometimes they’ve broken them up. It may make sense for a power or water company to be a sole supplier, and in that case governments have often used regulation to control their prices.

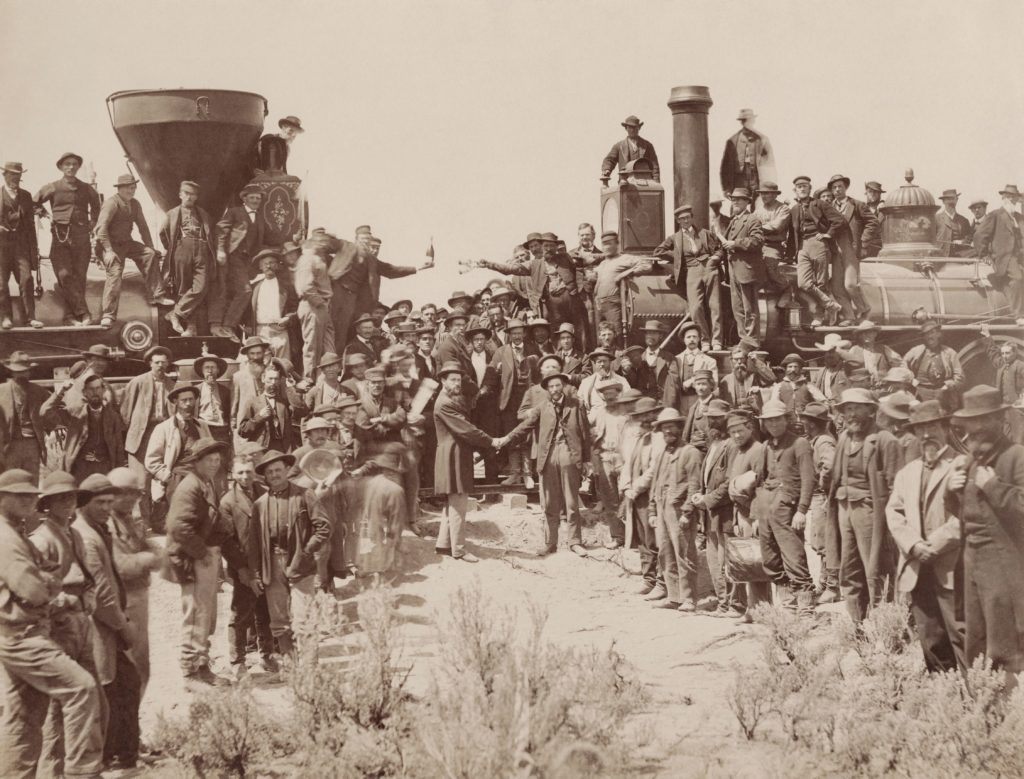

But the classic monopolies of the 20th century involved industries like steel and railways. In 1902, America’s most flamboyant President, Teddy Roosevelt, confronted the leading tycoon of his generation, J. Pierpoint Morgan, and fired the first salvo.

Morgan’s Northern Securities Corporation was an effort to control a large slice of America’s railways, and – why else? – enforce monopoly pricing. Roosevelt used the 1890 Sherman Act to stop this railway gamble in its tracks. And the US went on to break up the “trusts”[3. On US anti-trust law: Marvin Ammori, in Wired for October 16, 2012: “Monopolies: Anti-Trust Law Protects Consumers, not Competitors.” https://www.wired.com/2012/10/antitrust-is-supposed-to-protect-consumers-not-competitors/.], as they are known in the United States, in industry after industry[4. Some background here: Elena Holodny, “19 robber barons who built and ruled America,” in Business Insider for July 29, 2017. https://uk.businessinsider.com/robber-barons-who-built-and-ruled-america-2017-7.].

Is the new economy different?

In place of the old industrial and banking giants that used to dominate the global economy, we now have tech companies. Three of them have grown into vast monopolies.

Amazon dominates e-commerce. Among many striking statistics, it owns 74% of the e-book market. But it’s into other things too, like selling cloud storage and, just recently, buying Whole Foods, a US supermarket chain.

Facebook displaced early social-networking pioneers like MySpace and now commands 77% of mobile social traffic, with two billion monthly users. The aim is to sign up everyone on the planet. Excluding China, where the service is banned, they’re half-way there.

Google brushed aside Yahoo and other early search machines – and has never been challenged since. It now has 88% of global search advertising. Its aim, of course, is to have absolutely everyone use it to access all the world’s knowledge.

What’s more – and this is potentially sinister – between them, Facebook and Google account for 75% of referrals to major news and entertainment sites[5. Some data sources on Facebook and Google: Adam Hartung, “The Trend To Facebook Referrals Is A Risk To Google Search.” https://www.forbes.com/sites/adamhartung/2017/05/26/the-trend-to-facebook-referrals-is-a-risk-to-google-search/#242e21a16715. “40 Essential Social Media Marketing Statistics for 2017.” https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2017/01/05/social-media-marketing-statistics.].

Social networking and search are offered “free” to consumers in exchange for data. And data, as The Economist magazine has said[6. “The world’s most valuable resource is no longer oil, but data,” The Economist, May 6, 2017 https://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21721656-data-economy-demands-new-approach-antitrust-rules-worlds-most-valuable-resource.], is the new oil. They use (our) data to target ads, and they sell it on to others for similar purposes. From one point of view, both Google and Facebook are in the same business: advertising driven by user data.

Amazon is different. Its business model has been to build e-commerce market share to the exclusion of all else, including (at the moment) profits. Like the robber baron monopolies of the early 20th century, its approach has been predatory. It destroyed much of high-street bookselling, including the large US bookseller chain Borders. It fought viciously with the Hachette publishing group to keep book prices where it wanted them. A monopoly to customers in several sectors, in publishing it has operated as a “monopsony” – a dominant buyer, who can set prices with suppliers in the way in which monopolists set them for consumers.

The key to making monopolist profits, of course, is to stay a monopolist. Peter Thiel’s defence of monopolies includes the idea that they are “serial” in nature; in due course, a fresh disruptor will come along and send the current one packing. But this is disingenuous. If you’re a monopolist, absolutely everything depends on stopping that from happening. The incumbent advantage of these huge global companies is formidable. And if someone could become a threat? Buy them, like Facebook’s done with Instagram and WhatsApp.

What would Teddy do?

While Amazon sells things for cash, Facebook and Google seem to give things away. One estimate has it that these online “freebies” are worth $280 billion a year. One result is that users tend not to see themselves as “customers” and tend not to see Facebook and Google as “real” companies – like BP, Starbucks and British Airways.

Of course, this “free” use is not the result of generosity on the part of Zuckerberg, Brin and Page. It’s an optical illusion. Their business model makes it highly profitable for them to offer users social media and search services in exchange for their data. An illustration of the scale of data being bartered by users: in 2012 Max Schrems, an Austrian law student, asked Facebook for all his data. What he got was a pdf that ran to well over 1,000 pages[7. Olivia Solon, in Wired for December 28, 2012: “How much data did Facebook have on one man? 1,200 pages of data in 57 categories.” https://www.wired.co.uk/article/privacy-versus-facebook You can download your own data: https://www.idownloadblog.com/2016/01/18/how-to-download-facebook-archive/.].

Neither Facebook nor Google has offered a subscription-based alternative to their obscure barter business model. Why? Because it would alert their billions of users to what is really going on, as we hand over data and privacy for service.

Breaking up is never easy

Three huge challenges face any effort to treat Facebook and Google and Amazon as the anti-competitive monopolies that they are.

First, users like them. And because most people are users, that means that most people like them. They have become integrated into our daily lives in complex ways. They just don’t look like overbearing corporate giants run by the 21stcentury equivalent of the “robber barons” that Teddy Roosevelt tackled head-on. While Bezos is plainly a businessman, his company has a genius for consumer-friendliness. Zuckerberg, Page and Brin still look enough like kids who make fun stuff – and have joined the ranks of the multi-billionaires by some kind of fluke. The effect is dangerously disarming.

No-one refers to any of them as “tycoons” or “moguls”. The intimacy of our engagement with their businesses – we use their services in bed and in the bathroom and in the car – has blinded most of us to the fact that these young men have inherited the corporate mantle of JP Morgan and Andrew Carnegie – and that they run their companies just as ruthlessly[8. Natasha Bertrand, “How Amazon’s Ugly Fight With A Publisher Actually Started,” in Business Insider for October 7, 2014. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-did-the-amazon-feud-with-hachette-start-2014-10?IR=T .].

Second, as we’ve noted, we don’t pay Facebook and Google directly for their services – in contrast to the widely disliked cable and phone companies whose monthly bills are costly. The obscure data-for-service barter system they have developed leaves most users barely aware that they are consumers at all.

Third, these three companies have mastered the lobbying process; they are powerful players in Washington (and other capitals). As a recent article in the Financial Times by Rana Faroohar pointed out, “Big Tech has quietly become the dominant political lobbying power in Washington … to avoid regulatory disruption of its business model, which is now the most profitable one in the private sector.”[9. Rana Faroohar, “Release Big Tech’s Grip on Power,” in the Financial Times, June 18, 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/173a9ed8-52b0-11e7-a1f2-db19572361bb?mhq5j=e6.] They don’t just lobby politicians – the process is more sophisticated. According to Faroohar, Google alone has funded more than 140 Washington-related organizations with grants and sponsorship – to make friends and quieten criticism, “trying desperately and in myriad ways to avoid the ‘m’ word.”[10. Ibid: “Over the past few years, Big Tech has quietly become the dominant political lobbying power in Washington, spending huge amounts of cash and exerting serious soft power in an effort to avoid regulatory disruption of its business model, which is now the most profitable one in the private sector.”]

So where do we start?

A modest proposal

Even if monopoly pricing (the main monopoly bugbear) is not present (Amazon, at the moment, makes little profit) or obscure because of barter (Google and Facebook), governments must ensure the integrity of the market. They need to encourage innovation, and therefore a fair crack of the whip to new entrants as they challenge incumbents. So why permit takeovers of challengers? Why not push for tech solutions such as open APIs[11. API stands for Application Programming Interface – the protocols that enable one programme to speak with another. If they are made public, people from other companies can develop applications that interface with them. So, for example, you might not need Facebook Messenger to chat with someone using the service.] to set developers free to innovate?

Why can’t there be a dozen companies, some data-bartering, others subscription-based, enabling Facebook-type service – and inter-connected like our phone companies are?

Second, markets need pricing. Never before have we had major enterprises operating on the basis of a foggy barter. Data-for-service deals need to be explicitly priced, and cash alternatives (service for cash, or cash for your data) offered.

Third, to the extent that any of these companies is a natural monopoly like a water company – because, for example, that’s the only way to capture network effects or deliver economical service – it must simply join the list of regulated industries.

Fourth, monopsony effects (such as Amazon’s dominance of book-buying from publishers) are legitimate concerns if the integrity of the marketplace – as the health of small business – is seen as in the public interest.

Winning through freedom

It was Adam Smith who pointed out long ago that capitalism magically transforms the pursuit of private profit into a winning situation for all of us. But that is true only if the market is free to do its work. As the factors behind the monopolistic growth of the Unholy Trinity become increasingly prevalent in the global internet economy, securing a win for the consumers of the 21st century will require us to challenge their pretensions and encourage new entrants to compete with them.

This will involve facing down powerful interests, but that’s hardly new.

In 1602, Sir Edward Coke, doyen of English jurists, faced off against Queen Elizabeth I herself. In what is known as “The Case of Monopolies”[12. Key facts are given in the Wikipedia entry on Darcy v. Allein. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darcy_v_Allein.] he struck down a monopoly (for playing cards) that the Queen had handed to a courtier. Darcy Esquire v Thomas Allin, London Haberdasher and the arguments Coke used in his judgment are just as relevant today.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe