By Emily Boston, via Wikimedia Commons

This ‘UnPacked’ daily series is the focus of this week’s UnHerd podcast. Peter Franklin joined Tim Montgomerie and Ayesha Hazarika to discuss three of the latest columns – on Yimbyism, America’s opioid epidemic and the taxing of tech firms. Listen here.

***

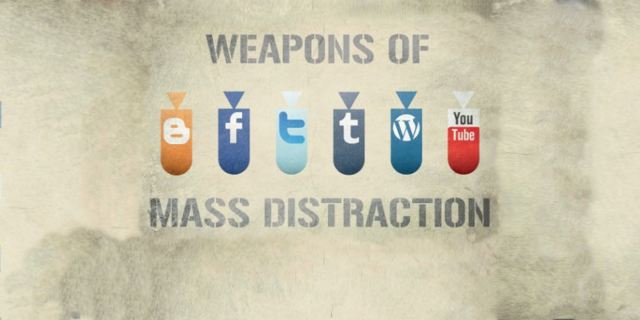

Yesterday, my subject was America’s opioid epidemic; today, I’m looking at a different form of addiction – the constant lure of social media.

If you’re on Twitter, Facebook or just plain old-fashioned email, there’s always some message, ‘mention’ or other notification that demands your immediate attention – and, of course, suckers that we are, we’re usually willing to give it.

Smartphone hardware and software is designed to ensure that we do. In fact, as Paul Lewis writes in the Guardian, research shows that people “touch, swipe or tap their phone 2,617 times a day.”

The ultimate aim is to sell advertising – and for that the tech companies need to draw our attention. Hence the concept of an ‘attention economy’ in which most of us are unpaid producers.

But where’s the harm in that? The print and broadcast media have been at the same game for decades. Why should we regard the new digital media as a special threat?

The answer lies in the ability of digital to insinuate itself into our lives. Consider the hardware. Compared to, say, a television, a smartphone is physically closer to us. If not in our hands, it’s within reach – on our desks, at the dinner table, by our bedsides. It’s always with us – as we work and play, eat and sleep. It’s always on – not just there for us to listen to or look at, but also to listen to and look at us. How, we interact with our phones is being continually monitored and the information used to ‘improve’ – i.e. make more addictive – the services provided.

Attention is a zero-sum game. If you’re focused on ‘A’ then, by definition, you’re not focused on ‘B’. When ‘A’ is the digital world and ‘B’ the real world, you can see the problem:

“There is growing concern that as well as addicting users, technology is contributing toward so-called ‘continuous partial attention’, severely limiting people’s ability to focus, and possibly lowering IQ. One recent study showed that the mere presence of smartphones damages cognitive capacity – even when the device is turned off.”

Perhaps it might be better to describe the ‘attention economy’ as a ‘distraction economy’.

One of the most interesting threads in Paul Lewis’s article is what he describes as “a small but growing band of Silicon Valley heretics” who are seriously worried about what their industry is doing to our minds:

“It is revealing that many of these younger technologists are weaning themselves off their own products, sending their children to elite Silicon Valley schools where iPhones, iPads and even laptops are banned. They appear to be abiding by a Biggie Smalls lyric from their own youth about the perils of dealing crack cocaine: never get high on your own supply.”

Lewis quotes James Williams, an expert in some of the key technologies, who describes the industry as the “largest, most standardised and most centralised form of attentional control in human history”.

The lengths that some digital experts go to protect themselves is instructive. Lewis mentions a product manager who hired someone to “monitor her Facebook page so that she doesn’t have to” and an industry consultant who has a timer switch to cut off his home from the internet.

They do these things because their personal productivity depends on it. In theory, each individual has a choice about how much time they spend online. In practice, however, there will be an aggregate effect on productivity that affects us all.

I wonder how long it is before a major economy decides to take collective action against the distracting effect of social media.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe