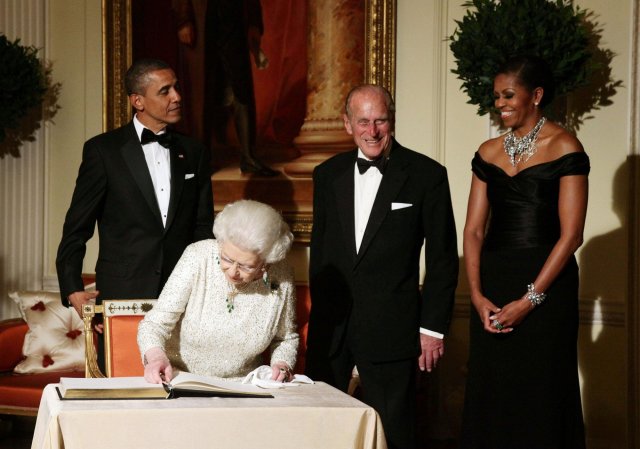

Yui Mok/PA Archive/PA Images

Every British ambassador hopes for a state visit by the Queen during his or her posting. Besides the automatic KCVO/DCVO that comes with it, a royal visit opens doors in the host nation like nothing else. “Access” is everything to a diplomat. Her Majesty sprinkles stardust that stays around a long time.

Likewise, a state visit to Britain, with the panoply of a ceremonial welcome on Horse Guards Parade, hospitality at Buckingham Palace and state banquet at Windsor Castle, can woo hesitant partners, renew flagging friendships, and bolster old alliances. The politicians and officials who accompany the Queen, or the head of state in the incoming visit, are obliged to speak with their opposite numbers in an atmosphere of cooperation. Things can happen that would take years to achieve routinely. At the very least, mutual knowledge is increased, especially of key players. One of the last inward state visits – President Xi Jinping of China in October 2015 – was notable for just this.

In diplomacy, people matter

Edmund Burke said “the principles of true politics are those of morality enlarged”[1. Letter to Dr William Markham, 1772]. The personal interplay of individuals is therefore important. The “Queen of England”, to use the shorthand, is a tangible link with the history that shaped the modern world – history of which statesmen are well aware. Contact with the Queen is therefore good for their own gravitas, and they are well aware of it too. In addition, the Queen’s personal morality – morality in the broadest, Burkean sense – gives Britain an almost unique standing in the world. She is proof that a country is more than its worst mistakes. Nowhere is this more important than with the Commonwealth.

No wonder Her Britannic Majesty is the government’s ace diplomatic card.

Playing that card, at home or abroad, requires skill. The two hundred or so inward and outward state visits (not including Commonwealth visits) since the coronation in 1953, listed on the official royal website, shows the Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s gameplay these past sixty years. Some visits were patently more successful than others. In 1978, at the height of the Cold War, President Ceaucescu of Romania – a communist dictator of Stalinist disposition – made a full state visit. Whatever it achieved, it failed to moderate the excesses of his regime, and ten years later he was ousted in a popular coup and he and his wife summarily executed.

At the time, Ceaucescu’s visit brought barely a protest, though at one stage the Queen reportedly hid in a bush in the grounds of Buckingham Palace to avoid a casual encounter with him, and told the staff to hide the silver. She and the nation understood the concept of raison d’État – that which must be done in the national interest.

O tempora, o mores. President Trump is no Ceaucescu. For a start, he could probably buy most of the palace silver. Yet in the case of a Trump state visit, not raison d’État but virtue signalling reigns. Foremost among the virtue signallers is Mr Speaker Bercow, who is returned to Parliament in a process akin to that of a pre-1832 Reform Act rotten borough. This paragon of modesty, dignity and good taste has arbitrarily decreed that the President of the United States of America, the leader of the free world, an Anglophile and evident ally in the struggle to make a success of Brexit, is unworthy of the honour of addressing the mother of parliaments. An address is one of the privileges of a modern state visit – one which, arguably, most underscores Britain’s claim to the moral high ground.

Taking courage from history

History suggests, however, that the government may be being unduly timid in its concern about discourtesy, protest and abuse. In 1904, a fat, disreputable newcomer to power made a visit to an unfriendly foreign country, with a mission to thaw the ice. He did so without attendant professional advice; indeed, the professionals were anxious about the visit doing further damage. He had one advantage, though (besides his position as titular head of the most powerful nation on earth): he loved the city he was visiting, and he was capable of great personal charm.

The man was King Edward VII, and the city Paris.

The French had long been Britain’s hereditary enemies, though things had improved from time to time after Waterloo. In the 1850s we briefly became allies (or, at least, cobelligerents) in the Crimean War and the Second Opium War (against the Qing Dynasty of China). In August 1855, Napoleon III having visited London in April, Queen Victoria even made a state visit to Paris to cement the new-found friendship, taking with her young Edward, whom she made kneel at the tomb of Napoleon Bonaparte in Les Invalides, ostensibly to pray for his soul (somewhat contrary to Anglican doctrine). However, by the end of the century, enmity had returned through colonial rivalries in Africa.

Then suddenly, with the Entente Cordiale of 1904, everything changed. Britain and France became undeclared allies against expansionist Germany. Diplomatic efforts were behind the entente, of course – notably by the French foreign minister, Théophile Delcassé and his opposite number, Lord Lansdowne, as well as Paul Cambon, the French Ambassador to the Court of St James (who suffered much in the cause of diplomacy, declaring of a meal at Windsor Castle in 1898, “La cuisine était detestable”) – but Edward’s 1903 visit helped create the atmosphere which made the entente possible.

The visit was not without opposition in France. One cartoon which circulated in Paris as a postcard, and reproduced by several newspapers, pilloried the playboy image of Edward when Prince of Wales – cigar and glass of absinthe in hand, a waiter hovering to pour him more, and a prostitute nearby, too. The French foreign office was beside itself with anxiety that insult would be taken by both the King and London.

They need not have worried. No offence was taken, and Edward’s charm worked magic. “Seldom can such a complete change of attitude have been seen as that which has taken place in this country during the last fortnight towards England and her Sovereign,” a Belgian diplomat reported to Brussels.

Time is not on our side

The excuse for denying President Trump a state visit is that presidents of the United States are usually invited in their second term. This won’t do. Both Presidents George W Bush and Barack Obama made state visits in their first term. They did, however, make earlier informal ones; and here, perhaps, is a useful (temporary) expedient. A visit next year to open the new American embassy south of the river would be an elegant pretext for a so-called working visit, in which the opportunities for gross discourtesy are avoided. But it cannot be allowed to substitute for the honour of a full state visit the following year. The damage a diplomatic snub might do far outweighs the benefits of virtue signalling. Standing by the United States of America in time of tribulation is what a good ally does. Besides, raison d’État requires it.

There is another reason why further procrastination is not an option. The Queen is 91 (and her consort 96); she is already cutting down her public duties. How many more state visits will she be able to host? The Prince of Wales can do much on her behalf, but he cannot sprinkle the same stardust.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe