Robot seals are already being used to help treat dementia patients – David Hecker/DPA/PA Images

It’s 2034, and you’re off to visit your aged uncle in a nursing home. The explosion in the number of elderly patients with dementia has placed huge pressure on resources, especially the human kind, so patients like him are being cared for part of the time by robots.

You find your uncle “sitting on a bench in the courtyard garden… with what looks like a baby seal on his knee. He is looking into its eyes, lost in a world, then he brushes its whiskers and tickles its nose with a slow finger. “Itchy-itchy-itchy-coo,” he says. The seal wriggles, gazes back at him and makes small, seal-like noises. [His] smile shows his pleasure.”

The ‘baby seal,’ called Paro, is quite the social animal:

“There is a lot of humour with Paro. Many of the patients anthropomorphise the seal, enjoy pretending that it is a real, living creature, with all the associated foibles. As well as the nurturing: ‘Let’s look after it and stop it crying’, a lot of people refer to its bodily functions,” says Jepson. ‘They’ll say [as a joke]: ‘Oh it’s farted on me!’ or ‘Don’t you go peeing on my leg!’ and then people will laugh, and the jokes will come in, and it creates a nice social interaction.’ Encouraging social interaction and calming distressed patients are proving to be two of Paro’s most promising uses.[1. Andrew Griffiths, Guardian, 8 July 2014; https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/jul/08/paro-robot-seal-dementia-patients-nhs-japan]

There are plenty of other robots around to help too. Some of them carry patients around, and can put them to bed. There are others that feed patients who can’t feed themselves. There’s a super-smart wheelchair that, on command, will turn into a bed, without the need for the patient to get out.[2. See the BioCentre report, p. 5, for these ‘rehabilitative robots.’]

Back to the future

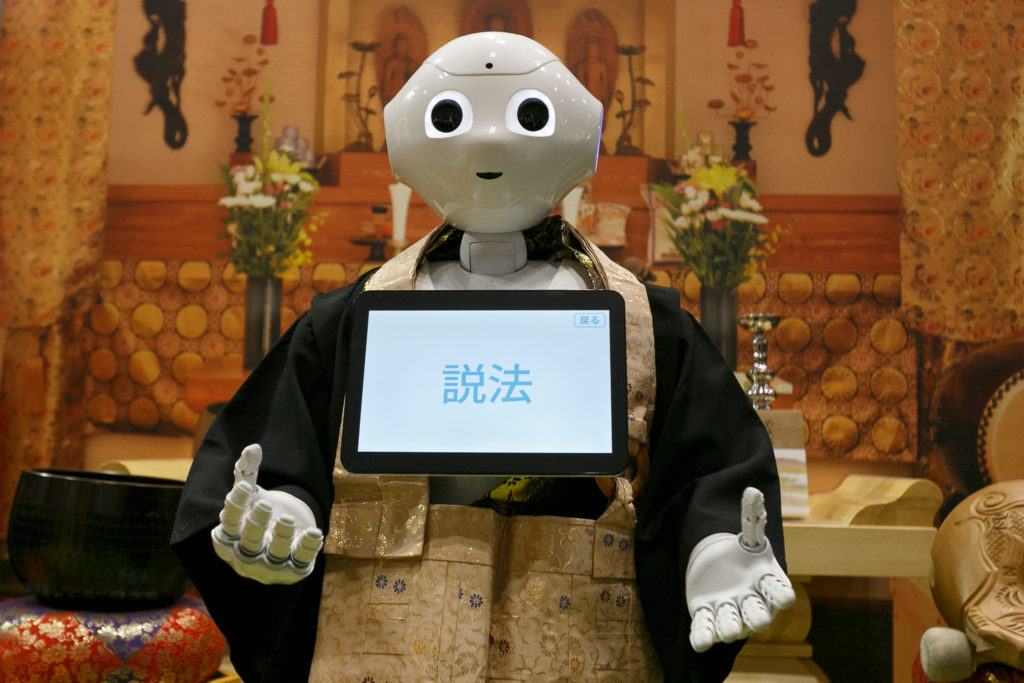

Of course, it isn’t 2034 at all. The Paro report was actually from 2014, and the quotes are from The Guardian newspaper. Tomorrow’s world has arrived early in the care of the dementing elderly. Paro the seal-shaped robot, costing Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) around £4,000, is being integrated into care regimes. And it’s just a small start. As the carrying robot and the wheelchair/bed robot and the feeding robot and a dozen more are tested and proved safe and cost-effective.

What’s going on? It’s unlikely that even patients with advanced dementia believe that Paro is a human being. They may see him/her/it as a grown-up version of the Tamagotchi children’s toy.[3. The Tamagotchi was a electronic device that had huge success after it was released in 1996. It didn’t look like a doll – more a kind of egg – but required to be treated like a baby (‘feeding’ and more) or it would malfunction. More than 76 million had been sold by 2010. The Wikipedia entry is well-referenced.]

Or perhaps as a pet. Pet therapy is widely used, so the idea of a robot pet is an obvious one. Are there ethical issues involved in giving pseudo-pets to people who can’t tell the difference?

And of course, this is just a start. Because even though Paro and other ‘social’ or ‘rehabilitative’ robots don’t come cheap, they are a good deal cheaper than people, and they can work around the clock. Already a range of these care robots are being developed. What’s important to recognize is that while we are a long way from a robot that can think and act like we humans think and act, there are plenty of machines that can do one thing or several things better than we can. Think of the wheel or the plough – or the pocket calculator. We don’t need to have a ‘humanoid’ that looks and sounds like one of us in order to outsource some, or perhaps all, of the tasks of nursing and social care to machines. And as costs squeeze our services, the incentive is plain.[4. The ‘humanoid’ robot still lives largely in science fiction. Whether Robin Williams’ classic performance in the classic 1999 film Bicentennial Man, or the creepier HBO series Westworld based on Michael Crichton’s 1973 film, sci-fi stories point up the weirdness of machines that look the same as humans. Paro and co are a long way from there. But they’re on their way: they look like pets.]

The hand that rocks the cradle….

But what about the other end of life – the other period of extreme vulnerability and cost? Once again, the Japanese – who have pioneered much of human lookalike global robotics – are in the lead. Again, the aim is very practical. Just as we shall need more people and resources to care for the growing number of longer-living elderly, so we need childcare – and in Japan there is a current ‘crisis’ in providing it. One recent report starts like this:

“Child care is a hard job, but somebody, or something, has got to do it.

“Japanese researchers have developed androids[5. ‘Android’ means a humanoid or human-looking robot] to meet that need, which includes happily reading that fairy tale again and again and again.

“The androids, which were created by a team of education and robotics specialists at a research facility in Abiko, Chiba Prefecture, are part of a larger system called RoHo Care. Short for Robotic Hoikujo (day care center), RoHo is being touted as a high-tech solution to the staffing crisis that forced the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry to announce emergency measures this week.

“’I never thought I’d see this day, but we’re now confident that RoHo could blaze a trail for child care worldwide,’ said team leader Makoto Hara.”

The plan is by 2018 to staff a typical daycare centre with only one human supervisor and four of the android machines. For up to 60 children.[6. Roy Bishop, Japan Times, 1 April 2016. “Robotics makes baby steps toward solving Japan’s child care shortage.”]

There are all sorts of benefits , including a way around the problem of recruiting humans to do the job.

“Unlike human day care staff,” the robot carers “don’t suffer from mental or physical fatigue. They’ll never tire of repeating the same stories and performing the same daily tasks,” said the chief researcher. What’s more, the voice “can be female, male or gender neutral,” said Yoshikazu Musaki, a specialist in early childhood education. “Its learning capabilities, coupled with the latest in artificial intelligence, will allow it to customize its care to each child.”

These are plainly androids, human-like robots, though the developers have decided that kids prefer a “jolly blob-like character” to a pseudo-human face. “We’ve combined elements of Barbapapa [a cartoon character], Baymax (a character from the film ‘Big Hero 6’) and my grandmother,” said one of the researchers.

They’ll know the kids by name, track their emotional and cognitive development, and report progress back to the family every day.

We’ll check in to see how all this is going in 2018.

Toys ‘R’ Us

The need to save money that is driving robot carers for the vulnerable at the start and the end of life is matched by a drive for entertainment on the middle. To be precise, for children. Where the iconic Barbie doll, first launched to the joy of little American girls in 1959, has rapidly caught up with the digital revolution.[7. Useful Wikipedia summary of Barbie’s story.]

In 2015 Mattel launched a Barbie powered by Artificial Intelligence that would connect through your home wifi system with a vast repository of conversations, so she could chat with your little girl and keep her happy. The New York Times reported on the marvel – and some of the problems – of this achievement. At one level it seems simply to be a Tamagotchi for the technology of 20 years later. From another, an early robot ‘friend’ for children whose successors will no doubt get smarter and more ‘human.'[8. James Vlahos, New York Times, ‘Barbie want to get to know your child’, 16 September 2015; https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/20/magazine/barbie-wants-to-get-to-know-your-child.html?mcubz=0&_r=1]

The Human Questions

It’s clear that whether or not we ever develop full-service humanoid robots – that look and speak and ‘think’ just like we do (a la Westworld) – the push for social and nursing care and early-stage education and toy machines that mimic human functions is powerful. Is it unstoppable? Are there limits to where we think it should go?

Do we like the idea that little girls and boys who give their toys imaginative personality and whose ‘imaginary friends’ follow them around – do we like the idea of their making friends with AI-programmed toy-oids?

Do we like the idea that elderly people, whose grasp on reality may be declining, are being palmed off on machines to keep them amused instead of real people? Whether they believe them to be machines, or think of them as pets, or perhaps – as they get more sophisticated – as real human beings?

And small children: are the Japanese right in seeing the key to early childcare as blob-faced humanoid carers who know everything about their charges?

Your answer may be a simple yes, or a simple no. Or it may be more nuanced. Or perhaps you feel you don’t know enough to come up with an answer.

But the questions need to be asked. They’re among the key questions of the 21st century.

Where are we going to be in 2034? It’s up to us.

FURTHER READING

There’s been surprisingly little public discussion of the rather significant start of the robotized care of the elderly. A recent scoping report edited by Matt James of the London think tank Biocentre (bioethics.ac.uk) is here.

If you’d like to buy a Paro, here are the suppliers’ details.

DISCLOSURE

I chair the board of the London think tank Biocentre (a charity) that is referenced in the notes and further reading.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe