Credit: iStock / Getty Images Plus

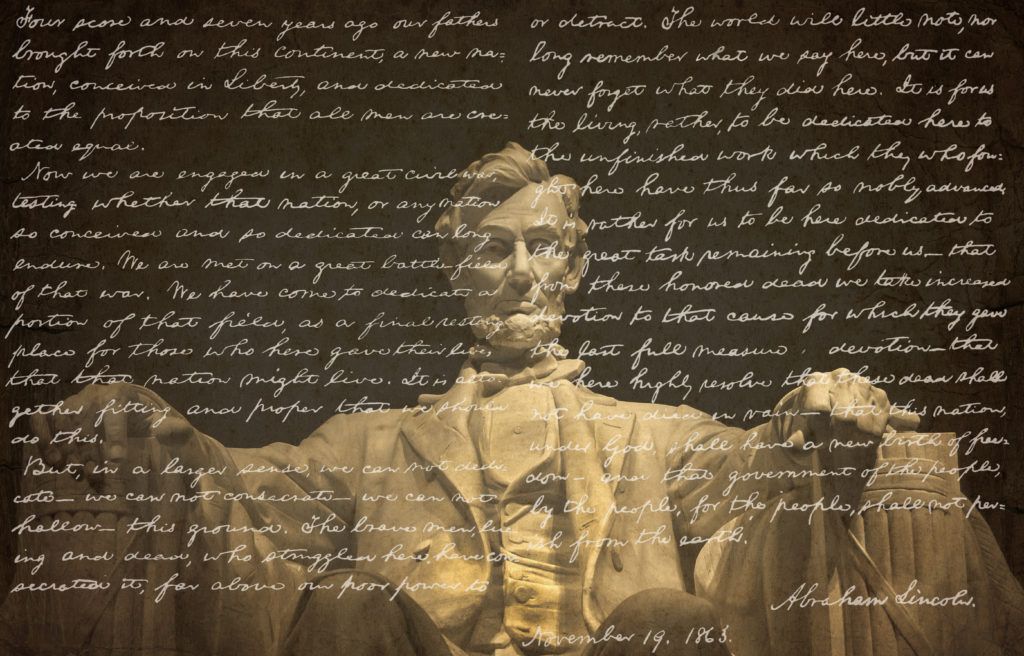

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past” is perhaps the most famous line of William Faulkner’s 1951 novel Requiem for A Nun. Set in Mississippi during the Depression, the book’s theme is spiritual redemption for past evils through suffering and the recognition of guilt. Barack Obama used Faulkner’s words in a memorable campaign speech on the legacy of slavery (“A More Perfect Union”) in Philadelphia on 18 March 2008.

Slavery and the Civil War are inseparable. However much apologists try to sanitise it as states’ rights versus the ambition of an overbearing federal government, the conflict was first and foremost about “the peculiar institution”, as slavery was decorously known. The Confederate states seceded from the Union specifically to preserve slavery, in which lay their invested wealth and the basis of their economy. The issue had been simmering for years, not just as a moral question but as an economic one. The South used “the peculiar institution” to distort the market and give itself an advantage over competitors who did not use slavery. Because slaves outnumbered whites in several areas of the South, the subjugation was also seen there as a necessary means of social control.

It came to a head in 1861 with the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency as leader of an avowedly abolitionist Republican Party. But if slavery and the fight to preserve add up to being a very present memory to black America, aggravated by the long denial of civil rights to ex-slaves and their descendants, white Americans still remember the huge number of lives lost in the Civil War (1861-65) itself. Traditionally, historians have put the figure at around 620,000: 360,000 for the Union and 260,000 for the Confederacy (it is calculated that 1.6 million men served in the Union army, and 800,000 in the Confederate). More Americans died in the Civil War than in both World Wars, Korea and Vietnam combined. That traditional estimate may understate the loss of blood, however. Recent scholarship suggests the death toll was between 750,000 and 850,000. In a country of about 30 million, of which the Confederacy numbered some 9 million (and of these, 4 million were slaves), the effect of such losses has inevitably been profound and enduring.

Why were the losses so high?

Why, with the North’s advantage in manpower and much else, did the war last so long (April 1861 – May 1865)?

How did its conduct leave such a bitter taste in the mouth of the southern states?

Brother Against Brother

The clue is in the name. Though sometimes referred to as the “War Between the States”[1. Also the “War of the Rebellion” or “Great Rebellion”, while the Confederates preferred “War for Southern Independence”.] it is universally recognised as the “American Civil War.” And war between peoples who have hitherto considered themselves as one is invested with a peculiar destructive energy.

First, though, the leaders of both the Union (Lincoln) and the Confederacy (Jefferson Davis, born the year before Lincoln in the same state – Kentucky) had to decide on a strategy for victory. For the South, this seemed easy: defend the borders and repel invaders. But its land mass was huge and its borders and its coastline therefore long. It would have the advantage of fighting on “interior lines”, but its railway communications were nothing like as extensive as those of the North (it had put its money into riverine transport); it could not move large numbers of troops strategically in the way that the North could. It did not have the same human or industrial resources as the North, and it had a large and potentially hostile slave population within its borders.

However, the North was not without its problems too. To begin with, its capital lay on the border. Across the Potomac from Washington was the South’s Virginia, and the Army of Northern Virginia was led by a succession of able generals – Beauregard, Johnston and Robert E Lee. Defending the capital would always be the first consideration but by what offensive strategy could the potential resources of the North be brought to bear successfully against the South?

There was no immediate answer, rather a series of battles at first between troops who found themselves in proximity to each other. Besides, the Union high command was confident of rapid victory over the Southern insurrectionists, for the North possessed a regular army, albeit small, while the South had only militias. However, the first of these haphazard encounters, at Bull Run (the river) outside the railway junction of Manassas, thirty miles south-west of Washington, proved chastening: 40,000 men, each side roughly equal in strength, fought a very old-fashioned battle, hand-to-hand. The day ended with Union troops in full flight for the capital.

Though a smallish-scale affair compared with later battles, First Bull Run nevertheless had strategic consequences. It disheartened the North and persuaded the South that ultimate victory was possible. Consequently each side began to mobilise its full resources. Yet while the South could stick with its strategy of the defensive, the North would have to find a way of defeating a polity which, as a confederation (a largely agrarian one too), had no obvious centre of gravity.

The Union’s first strategic manoeuvre was an attempt in the spring of 1862 to take Richmond, Virginia from the south-east by sending troops by sea to the tip of the peninsula at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. It failed, largely because of the hesitancy of the commander-in-chief, George McClellan. Lincoln removed him from command in November, and the Army of the Potomac returned to futile frontal attacks close by Washington.

“War is Cruelty”

A successful strategy emerged more by accident than design later that year after General Ulysses S Grant took Forts Henry and Donelson and began the North’s first serious penetration of the South – down the Tennessee River. It would become known as the “Campaign in the West”, and notable for Grant’s aggressive spirit –living off the land, and single-minded attritional battles. In two days’ fighting at Shiloh each side suffered a casualty rate of about 20%. In Grant’s words, victory required the “effusion of blood”, as opposed to the previous strategy, which had been more akin to fighting gently in the hope of weaning the South away from war. The North was in a far better position to replace casualties than was the South, and the war would therefore become a body-count.

Grant’s success at Shiloh began the bisection of the South; and with bisection could begin its fragmentation. The Confederates inflicted a high price on Grant’s advance, however, contesting every river crossing and piece of high ground. In turn, Grant made the defenders pay heavily. Then in November 1864 after the capture of Atlanta (largely burned down), he unleashed General William Tecumseh Sherman – another general who believed in ruthless tactics (“War is cruelty and you cannot refine it”) – for the legendary march through Georgia. “I will make Georgia howl”, said Sherman, and indeed he spared them little:

Hurrah! Hurrah! We bring the Jubilee.

Hurrah! Hurrah! The flag that makes you free,

So we sang the chorus from Atlanta to the sea,

While we were marching through Georgia[2. Last verse of Marching Through Georgia, Henry Clay Work’s triumphalist song of 1865].

Meanwhile, Lee mounted two huge raids into the North – “raids” because they had no prospect of strategic success or consolidation. They culminated in the bloodiest battle of the war: the infamous Battle of Gettysburg on the 1st to 3rd July, 1863. Approximately there were 50,ooo casualties – a rate of 30% – and it was the high-water mark of the Confederacy, if a battle with such a loss of life could be thought of in such terms.

The South was in fact slowly bleeding to death. Martin Scorsese’s 2002 film Gangs of New York portrays the city’s bloody anti-draft riots of July 1863 (at least 120 were killed). There was no comparable protest in the South, but resentment was increasing. The Confederates had been first to resort to the draft, in April 1862, with all white males between ages 18 and 35 required to serve three years, later extended to 17 and 50. There were exemptions for those whose occupations were critical to society or the war effort, and until December 1863 a draftee could hire a substitute. This was irksome enough for a poor white, but even more controversially, the “Twenty-Slave Law” allowed exemption for one white man from a plantation with 20 or more slaves – because there might otherwise be no one to run it and manage the slaves; and, of course, white women would be “vulnerable.” Poor whites complained that it had become “a rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight.”

Desertions began to increase.

The North had a 30-to-1 superiority in arms production, a 2-to-1 ascendancy in manpower, immeasurable advantage in commercial and financial resources, and a functioning government. It also had the statesmanship and strategic instinct of Lincoln, for whom president of the Confederates, Jefferson Davis, was no match. Yet the ability of an enemy that was economically outclassed, as well as outnumbered, to prosecute a struggle on such a large scale is still mystifying. Perhaps this explains why in parts of the South the war is not entirely past.

Look Away! Dixieland

For all the ultimate evil of the cause, however, one can have only admiration for the unremitting bravery of Confederate soldiers – and professional admiration for the dexterity of many of their generals.

Question: How, therefore, should that soldierly virtue be honoured, separate from the issue of jus ad bellum?

Answer: With sensitivity, without defiance, without any desire to promote the so-called “Lost Cause of the South.” To do otherwise politicises the deaths rather than honours them. The actual battlefields, many of which are national monuments, are places of sober commemoration, with war stripped of vainglory; names and numbers on memorials there have resonance in due context. The battles themselves are commemorated on the colours (standards) of the various National Guard units that fought, memorialising the soldierly virtue to which present-day guardsmen, white and black, aspire. There is a barrack block at West Point, the US Military Academy, named after Robert E Lee; it honours his record there before the war as a reforming superintendent – and, no doubt, his capability as a general in the field. Cadets know, however, that as an insurrectionist he paid the price by the confiscation of his estate at Arlington, Virginia, now the National Cemetery.

In the public space the issue of whether statues were erected as, and remain, respectful memorials to the fallen, or are merely attempts to “put blacks in their place”, can only be a matter for judgement; but judgement by due and local process rather than by national protest or shrill entryism. The “thin end of the wedge” argument against removing any statue – President Trump’s “What about Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, slave owners both?” – is flaccid. As Mitch Landrieu, Mayor of New Orleans, made clear in his “Cornerstone Speech” of 19 May 2017, marking his city’s removal of the fourth and final monument to the Confederacy, the issue is a particular one, and fundamental[3. Transcript of speech and video, via Slate.com]:

“The historic record is clear: the Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and P.G.T. Beauregard statues were not erected just to honor these men, but as part of the movement which became known as The Cult of the Lost Cause. This ‘cult’ had one goal — through monuments and through other means — to rewrite history to hide the truth, which is that the Confederacy was on the wrong side of humanity.”

Confederate statues are also, however, monuments to defeat, no matter how unintended. Perhaps that is how those who feel oppressed by them can live with the statues until the further passage of time, or men of Landrieu’s sensibility, bury them.

***

FURTHER READING

HistoryNet’s Civil War timeline.

Explaining the current removal of Confederacy monuments;

WHEN WERE CONFEDERATE MONUMENTS ERECTED?

The graph comes from fastcodesign and you might also be interested in this short “Mic” video.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe