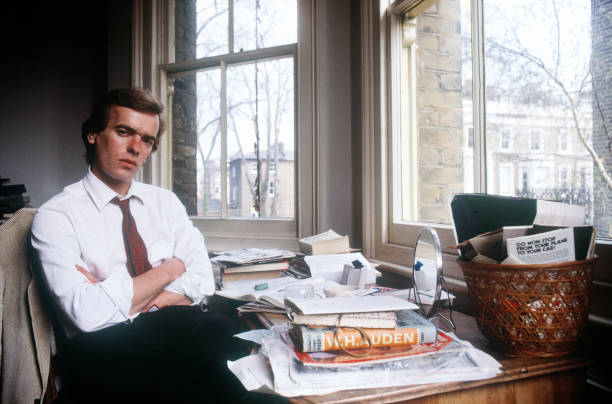

‘The reader-writer pursues his own fiction writing as masculine self-assertion’ (Photo by Ulf Andersen/Getty Images)

A strange and telling bit of literary trivia is that two of the greatest English-language novelists of the last half-century — Cormac McCarthy and Don Delillo — were not big readers when they were boys. Both took up reading as young men, and, indeed, much of their ardour as readers was sparked by the same author, William Faulkner. This is also telling, I think. From this pair of details a picture of incipient literary ambition comes plausibly clear. As young men with some thrilling but unformed sense of the talent they carried, McCarthy and Delillo read the famous prose of William Faulkner — earthy and recondite, vernacular in its music and grand in its thematic reach — and had two thoughts or intuitions, more or less at the same time. The first was: This stuff is amazing, like the greatest thing for a person to attempt and achieve. The second was: I can do that.

I think the spirit of this writing got inside them as they read and soon their own thoughts were infused with it, so that their internal monologues took on the rhythms and diction and authorial attitudes of William Faulkner. From this they came to believe themselves worthy of the great endeavour, to write at the William Faulkner level, because, simply in thinking their private thoughts, they already were writing like William Faulkner. Bits of their experience already were being milled into Faulknerian sentences, with which they would sometimes narrate their lives to themselves more generally, in paragraphs.

I was not in their heads and so I can’t absolutely confirm that this is how Cormac McCarthy and Don Delillo came to want to write their great novels, but both of them began to write seriously very soon after they began to read seriously, which suggests I’m onto something. And anyway, I was in my own head when the thing I describe happened to me. Like them, I read very little as a boy. I was physically restless and mentally scrambled, and also the third of six loud children born in an eight-year span to my poor mother. I lacked the cognitive and bodily inclination to read for pleasure, as well as a quiet place where I might try it, until I was done with college.

Or almost done. I was in my final term, student-teaching at a rural high school in Michigan, bored on a warm Sunday in a tiny village roughly 80 miles from both my home town and my college town, when I cracked open my gigantic literature anthology and began to read a short novel wedged, somehow in its entirety, amid the hundreds of poems and stories also gathered into the fat book. Yes, I was an English teacher at that country school, and an English major at my undistinguished university, and I’d liked the fiction I read for my classes, but not enough to read the stuff in my free time — until I opened my Anthology of American Literature, randomly as I remember, at the first page of Goodbye, Columbus by Philip Roth.

Unlike the novels of Faulkner, McCarthy, and Delillo, Roth’s fiction is not distinguished by self-consciously daring and luxuriant prose. What Goodbye, Columbus offered instead, to a reader like me, was voice, attitude, the funny and haughty and brainy commentary of its young narrator, Neil Klugman. Before I had even finished this little novel, my thoughts were taking a Neil Klugman or Philip Roth sort of form. I was describing things as they might. Of course I desired Brenda Patimkin right away. I also started wishing I was Jewish. And, almost immediately, I started wanting this new activity I was performing in my head, this mental making of Rothian sentences, to define me in some larger sense. I thought it should. From what I could tell I was really good at it. Reading Philip Roth I thought, I can do that.

In other words, before I’d even finished the first “literary” novel I’d ever found myself reading merely because I liked it, I started thinking I could be a novelist. I don’t relate this to compare myself with McCarthy and DeLillo, but rather to illustrate how far down the ladder of literary talent this tendency can be found. I suspect that, for certain readers, perhaps especially reluctant or belated ones, the thrill of discovering a love of serious and stylish fiction translates very quickly into a sort of literary will to power.

It might be by accident or obligation that the type of person I speak of becomes a reader, opening a book because there’s simply nothing else to do on a Sunday afternoon, or dutifully doing the reading for a university course, but then continuing as an avid reader because reading now fuels his uplifting hubris about writing, because that one book he stumbled on got the stylish sentences going in his head. This sent him after other books that might do the same thing.

You’ll notice that I dropped the coy neutrality and started using masculine pronouns just then. The particular reader-writer, the “type of person” I’m referring to in all this, is a male type of person. I’m dealing in gender stereotypes here. This is a risky and suspicious activity, I know, but these stereotypes are so consistently affirmed in both my reading and my personal experience that I feel I can use them as a sort of crude literary sociology. And these stereotypes are consistent with a phenomenon that comes up a lot when people talk about literature and publishing, the fact that men read very little fiction anymore, and, when it comes to the publishing category called “literary fiction”, they read almost none. Some gloomy ironies attend this fact, which I’ll go into below.

In my gender stereotypology, the woman fiction writer has been reading her whole life. She read easily and prodigiously as a girl, consuming and then producing stories that grew in sophistication as she herself grew older. Thanks to her fast and effortless reading, she developed a capacious feel for the arc of character, the full span of narrative time, the novel as a single experience, a single order. Her mature writing serves these broader elements. It is thus less showy than that of her male counterparts, more story- than style-oriented. By contrast the male reader-writer in my scheme came to reading as McCarthy and Delillo did, fairly late, perhaps after finding reading unpleasant or difficult when he tried it as a boy. His reading, when it did begin in earnest, was spurred by encounters with novels written in daring or quirky prose or bearing some other bold stylistic signature.

This style aspect is key. The male reader-writer in my stereotype understands writing, when done by the masters he admires, as a sort of exalted mischief — like the laddish riffing of Martin Amis and that early Philip Roth, or Delillo’s droll tabulating, his deadpan dropping of synecdochal nouns, an uncanny comic method whose influence is obvious and everywhere among lesser (male) writers. Perhaps consciously but at least subconsciously, our reader-writer pursues his own fiction writing as masculine self-assertion, and also — in rough consonance with Harold Bloom’s famous theory — as a quest to commit a few Oedipal murders, to transcend and thus kill his literary influences with an even more daring, more excellent, more distinctive style.

There are of course exceptions to these gender stereotypes in current fiction. For example the best, most intoxicating novel I read in the last year was Lauren Groff’s Matrix, which — with its supersaturated prose and Bunyanesque heroine, a polymathic giantess who rules a surprisingly sexy medieval convent — calls to mind male novelists like David Foster Wallace and John Barth more than any prominent female novelist I can think of. By contrast, Jonathan Franzen’s intricate, stylistically modest family sagas code as fairly female in my scheme.

Still, despite their imprecision and offensiveness, these stereotypes have real descriptive value. Indeed, much feminist criticism of toxic and laughable masculinity in the worlds of writing and publishing seems to assume some version of them. The partly justified, often philistine, and increasingly pointless mockery of male literary striving that became popular in the 2010s — exemplified by the “Guy in Your MFA Program” Twitter account and subsequent book, and their many imitators — leans on and propagates categories that resemble mine, even as its adherents would surely repudiate my gender stereotyping on grounds that it’s gender stereotyping.

But I’m less concerned with the exalted strata inhabited by Lauren Groff and Jonathan Franzen, who don’t have elderly neighbours and helpful loved-ones suggesting that they “self-publish”, than with the lower levels where most male reader-writers read and write. Shouldn’t the final collapse of literary reading among other men be something of a bummer to them? Shouldn’t the idea that their potential audience has largely disappeared kill their desire to keep writing?

In these times of hegemonic psychotherapy, many educators and functionaries would answer “No! Of course not!” Writing is fundamentally a mode of self-expression, they believe. It should be an end in itself, its own reward. Teachers of writing, at every level from primary schools to MFA programs, often base their writing pedagogy on this assumption, implying or even stating that the point or goal of writing is “finding your voice”, which means that a writing effort could be considered successful if it resulted in this bit of therapeutic self-discovery and nothing else. But the male reader-writer wants something very different from this. He’s on a quest to kill his Oedipal fathers. He writes because he thinks he is, or might be, uniquely excellent at writing. His standard for success in a writing effort is having it read by people who agree that it and he are excellent. For him the truly therapeutic outcome is not him finding his voice but other people finding his voice, and then declaring in newspapers and magazines and end-of-year award ceremonies that it is the best voice.

But in order to do that he has to get published, and in order to get published he needs a publisher to believe he might have an audience. It’s true that, while male fiction readers rarely read female authors, women fiction readers often read male authors. So he has that going for him. Still, if our reader-writer is writing as a mode of masculine self-assertion, publishers are going to expect his audience to skew male. He surely wants women readers, but his paradigmatic reader is another man, if that man can be assumed to exist — and on this point the numbers are extremely discouraging. A statistic much-repeated is that women buy 80% of published fiction and men only 20%. And it is largely agreed-upon in the publishing world that the imbalance is even greater, perhaps much greater, when it comes to literary fiction — as opposed to other fiction genres such as fantasy, science fiction, and especially spy novels and military thrillers, which sunburnt men in Bermuda shorts can often be seen reading on airplanes.

This is obviously a problem for publishers, who want all the genders shelling out for their books, but for some commentators it represents — as either symptom or cause — a moral problem. In two recent articles, male commentators agonise over the lack of literary reading by their fellow men. Writing in GQ, Jason Diamond confides that reading quality fiction made him a better person. He believes it might help other men gain “a better understanding of what drives… people to do terrible things” — the implication being that men who don’t read novels are perhaps at greater risk of doing terrible things themselves. In the Daily Beast, Jeff Hoffman offers a nearly identical lesson about men being at moral risk because they don’t read award-eligible fiction. Hoffman points to various small-n, non-randomised studies that claim to find an empathy boost from reading novels, especially for teen boys. The fake science is a minor problem, though. The more basic problem is that, for boys and men looking to enjoy and not just endure their lives, this eat-your-vegetables case for reading literature is more likely to stigmatise than encourage it. Of course, it’s easy for me to criticise such earnest wrestling with the issue, instead of offering my own suggestions. Then again, I’m not convinced it is an issue, and, anyway, I suspect my own case for reading good fiction — it gets the stylish sentences going in your head — has limited resonance in the larger world of men.

As to the supposed moral problems, I haven’t noticed any among men I know, but the statistics about women and men and literary reading are corroborated in my experience, and with almost total fidelity. Most women I know who went to university and maintain some cultural interests — women who see serious movies occasionally, who like the idea of museums and sometimes visit them, who are willing to converse about decent TV shows as a way to survive a dinner party — read at least a few literary novels a year. But, most of the men I know — men from my local parenting and social worlds, who have university degrees and respectable taste in television — read virtually no literary fiction, though some read sci-fi or detective novels. When my kids were little I met a fellow dad who told me (probably because I’d gone on at tedious length about the novel I was writing) that he had just finished reading a well-regarded recent novel. I thought, “Finally, a dad I can talk fiction with.” It wasn’t until several years later that he and I finally sat down for a cup of coffee. I started talking about contemporary fiction, assuming he was keeping up with literary things like I was, but it turned out that the novel he mentioned when we first met was the last one he’d read.

Conversely, when I do meet a man who’s an active reader of serious fiction, our conversation usually travels a familiar path. I learn that we like the same edgy, stylistically daring types of fiction, and that we’ve read many of the same recent novels. Sometimes the overlap in our reading seems quite improbable, given how little-known and low-selling these novels can be. A couple years ago a man I didn’t know mentioned to the group of people we were in that he was a huge fan of the Irish writer Kevin Barry. I’d just finished reading Barry’s brilliant, edgy, stylistically daring novel The City of Bohane. It was my new favourite novel! What a coincidence! But then, well, to make a long story short, this other Kevin Barry fan and I were eventually exchanging manuscripts, each of us reading the novel the other was currently “working on”. That’s right, we were both fiction writers, of the unpublished variety.

Further, on the rare occasion when I meet another man with a serious interest in literary fiction, I typically learn that he and I like many of the same edgy, stylistically daring writers, and, with absolutely zero surprise, I also learn he’s not just a reader. He’s a reader-writer. Like me he has at least one unfinished novel on his laptop. The identification I experience in these moments has become a little deflating, I have to admit, unflattering for both of us. Ruefully I consider this other reader-writer and think, “You too.” Even more ruefully, I think of the absurd ouroboros of literary creation and consumption that we reading-writing men make up — reader-writers writing for the small population of other readers who also write. The intimations of cultural glory I once felt while reading my literary heroes and thinking “I can do that” would have been much less seductive had I known my potential audience was, basically, me.

I felt this gloomy identification while reading those two earnest articles on the crisis of non-reading men that I cite above. I was mildly depressed but entirely unsurprised when, in each article, the author lets on that he, alongside his admirable, gender-atypical reading of literary fiction, is also a writer of it. “You too,” I thought, ungenerously. Still, I should give these articles a little credit. They don’t seem to realise it, but both authors have revealed the one reliable method for solving the urgent problem they’ve identified, the one proven way to create the empathic, evolved, morally enlightened type of man who reads literary fiction — convince him to become the grasping, vainglorious, most likely deluded type of man who writes it.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe