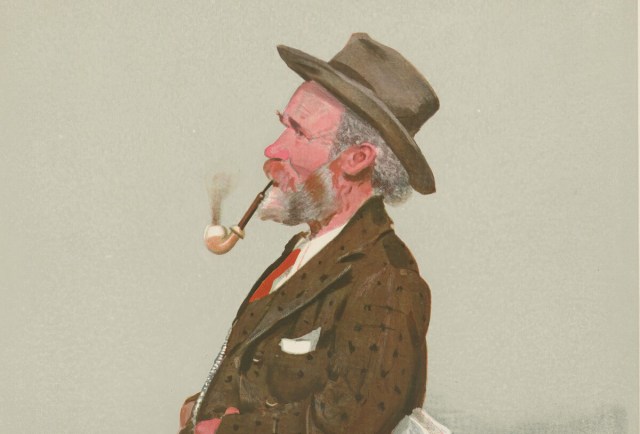

A 1906 portrait of Keir Hardie in Vanity Fair (Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

In the freezing West Riding winter of January 1893, around 120 miscellaneous radicals and reformers met in Bradford’s Labour Institute — originally a Wesleyan chapel, later a Salvation Army barracks — to debate the creation of a new political body. Though history may remember this meeting for the uplifting oratory of the curiously-dressed MP for West Ham South, Keir Hardie (deerstalker, dogs-tooth knickerbockers, purple cravat, white canvas shoes), it proved a fractious gathering of unruly tribes.

The delegates chose as their treasurer one John Lister of Shibden Hall, a maverick local squire — and kinsman of the now-celebrated cross-dressing châtelaine of Shibden, Anne “Gentleman Jack” Lister. Bernard Shaw burbled; Keir Hardie thundered (not least against the public house, “strongest ally” of “the usurer, the sweater and the landlord”); Edward Aveling (Karl Marx’s son-in-law) observed in dismay; Dr Richard Pankhurst from Manchester demanded ideological purity. The squabbling throng, however, decided against any titular endorsement of Socialism. They named their newly hatched entity the “Independent Labour Party”. Independent, that is, of the Liberal Party political machine that had so far — and would for years to come — sponsored, supported and tried to control most “Labour” and trade-union candidates for public office.

It would have stunned most of the Bradford delegates (not to mention their many mockers) to know that, 130 years on, the descendant of the 1890s ILP stands poised not only to enter government again but to do so with a (potentially) enormous majority. And with a leader named for its oddly clad orator. Pundits routinely examine the longevity, plasticity and flair for re-invention displayed by the Conservative Party (they will be doing so again soon). Yet Labour’s survival as an electoral force from the 1890s into the 2020s calls for just as must perplexed scrutiny — even if the ILP itself first fused with MPs of the Labour Representation Committee into a broader “Labour Party” (with Hardie as the first parliamentary chairman), then split, then re-joined, then faded into oblivion.

Labour legend, embraced by friends and foes alike, tells of a movement divided first, last and always between Left and Right, between thoroughgoing socialists and moderate reformers. Indeed, that 1893 conference voted both for collective ownership of the means of production and for a raft of standard Victorian radical-Liberal policies: not just the eight-hour day, payment of MPs and graduated income tax but “the abolition of indirect taxation”. Good luck with that one, then or now.

The reality, however, was stranger, messier — and far more interesting. Labour began as a motley mash-up of rationalism and mysticism, self-interest and self-denial, practical sense and nebulous idealism. It was (and maybe is) deceptive to carve simple binary lines into this over-stuffed fruitcake of a social force.

Hardie’s biographer, Kenneth O. Morgan, records that the passions of the ILP’s oddball prophet included “thought transference”, “belief in a previous incarnation for humans and for beasts alike”, Druids, fairies, faith-healing and “the sustaining force of Mother Earth”. When he had an affair with the much-younger feminist Sylvia Pankhurst, Hardie would read her “extracts from Shelley, Byron, Scott, Shakespeare and Whitman” over scones and tea at his Holborn flat. Hardie’s current namesake, bound to a doctrine that might be dubbed Extreme Normalism, sadly has little to say about all that.

From the fun-loving, ale-quaffing cyclists of Robert Blatchford’s Clarion clubs to the vogue for Spiritualism that saw Hardie (also in 1893) attend a séance to seek otherworldly guidance on Irish Home Rule, the Labour movement in Britain grew not just from Fabian statistics and Methodist sermons. It sprouted from a pungent late-Victorian mulch of literary visions, spiritual revivalism, rustic nostalgia, humanitarian activism and (not all that often) workplace militancy. Henry Pelling, author of classic histories of the party, affirms that “the faith did not stand or fall by the accuracy of facts and figures” but rested on “deeper and simpler forces of human nature”. He points out that 19th-century literary seers — John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle above all — meant much more to Labour pioneers than “any writers more fully versed in the abstractions of political economy”. H.M. Hyndman, head of the overtly Marxist Social Democratic Federation, despaired of the woolly dreamers around him and led the SDF off into its purist wilderness. (Hyndman, by the way, was also a rabid antisemite and county-level cricketer: right-hand bat, Sussex.)

Among the 20 English delegates at the Second Socialist International in Paris in 1889 were not only Hardie and Eleanor Marx but William Morris and the patrician writer-adventurer (and former gaucho) R.B. Cunninghame Graham. Not just Liberal but High Tory currents fed the wider stream. In around 1900, journalists could casually refer to “Tory socialists”. Some Tories backed Labour candidates in order to split the Liberal vote. When, in December 1910, Hardie won re-election at Merthyr in South Wales, he trailed what Morgan calls “his private army of socialists, suffragettes and ‘new theologians’” in his wake. The movement began, and continued, as a bizarre hybrid in which the material betterment of the industrial working-class jostled with a rich array of what sceptics might call “luxury beliefs”.

Hardie himself boasted that the ILP never had “a hard and dry creed of membership”. As he agitated for women’s suffrage, world peace or colonial independence, he confirmed (in Morgan’s words) “how easily his unique concern with socialism could be set aside”. Hardie, indeed, claimed that socialism in Britain appealed chiefly to “the intelligent well-off artisan” while the underclass quaffed Tory booze and Tory promises: “It is the slum vote which the Socialist candidate fears most.” In many ways this patchwork fairground of cross-class radicalism — in which vegetarians, teetotallers and occultists thrived as easily as horny-handed union organisers — defined Labour from the off. Many older trade unionists, in fact, maintained a stubborn loyalty to the Liberal Party until the First World War. You might say that the cranks first turned Labour’s engine. Why should that eccentric legacy not count as a cause for celebration, not embarrassment?

It feels apt that a new account of this frothing ferment should take the form not of a sober-sided history but a sprawling, ebullient, often-comic novel. The Night-Soil Men by Bill Broady begins with that inaugural Bradford meeting and then, over almost 500 galloping pages, follows the careers of a trio of ILP pioneers. Wisely, Broady gives the legend-encrusted Hardie only a walk-on part. Instead he tells the interlocking stories of Fred Jowett, who moved from woollen mill “overlooker” and Bradford councillor to Minister of Works in Ramsay MacDonald’s 1924 Labour government, of Philip Snowden, the Keighley tax inspector turned Labour economic wizard and the party’s first Chancellor of the Exchequer — and, unforgettably, of the elusive Victor Grayson.

Victor who? Once called “the finest mob-orator in England”, Grayson was a volatile, charming, charismatic Left-wing firebrand. From 1907, when he sensationally won a by-election, he briefly served as a “Labour and Socialist” MP for Colne Valley. But his sectarianism tore the ILP apart, and he resurfaced as a jingoistic Great War nationalist before disappearing, without any trace, in 1920. He was last seen in an “electric canoe” heading for an island house in Thames Ditton owned by the conman Maundy Gregory — chief honours salesman for Lloyd George.

Speculation over his vanishing act has persisted since. Plausible later sightings, up to the late Forties, place him everywhere from Madrid and Western Australia to Herne Bay. Grayson was also a voracious hedonist and libertine who loved, and slept with, more men than women: imagine a pansexual Boris Johnson of the far-Left. For Grayson, “the sins of the flesh were no sins at all”, while sex with men meant “merely an extension of shaking hands”. Broady shows him vigorously practising what he preached.

In spite of Grayson’s pyrotechnic progress, there’s something heroically off-trend about Broady’s novel. Late-Victorian blokes from Yorkshire and Lancashire discuss, and do, local politics at length amid dripping ginnels, fuggy bars and foggy moors. One can imagine publishers’ acquisition meetings in London and New York spluttering into their decaf oat lattes over the torrential talkiness and outrageous provincialism of this book. More fool them.

Broady brings tubfulls of humour, drama and fizzing exuberance to the ILP leaders’ zigzag journey from mill, market-place, pub and chapel to council-chamber, parliament and cabinet room. He takes ideas seriously but he makes those ideas dance. And he treats the historical record with scrupulous care while letting imagination take wing where the sources stop. If the recklessly randy Scouser Grayson can threaten to run away with the show, then the dogged welfarist Jowett — forever with “the smell of excrement” from Bradford slum privies in his nostrils — and Snowden, the disabled platform spellbinder who became an austerity-promoting iron Chancellor, more than hold their own. This is a high-spirited, big-hearted but deeply tender — sometimes lyrical — work about people, ideas and places generally thought fit only for the coarse-woven cloth of political prose. If Broady tips a straw boater to the cheery buoyancy of H.G. Wells, he nods too towards D.H. Lawrence’s grasp of the roiling passions beneath public masks.

The Night-Soil Men makes it plain that Labour began its flourishing in strange, mixed soil. Grayson, the revolutionary thrill-seeker who believes not in “The People” but “individual men and women who want a better, freer life”, speaks the language of the Scripture he learnt in Unitarian college. Yet he voices the sort of liberationist zeal more common in the movement now than then (though it’s hard to picture him marching behind a LGBT+ banner). Jowett, who aims to save souls by upgrading sanitation, keeps faith with the step-by-step emancipation of indoor toilets, running water, council houses and (one of his great crusades) free school meals. Snowden segues from the woozy idealism of his celebrated oratory (almost a match for Grayson’s) to the chilly fiscal orthodoxy of his time in office. Sound money and balanced budgets become stations along the way to the Universal Love that his high-minded wife Ethel (also a noted feminist) loudly proclaims.

As Labour types, the troika exists in the 2020s as recognisably as in the 1900s. You could almost map Broady’s triptych of characters onto the three traditions identified by the deep-thinking (but now retired) Dagenham MP Jon Cruddas in his recent book A Century of Labour. In this light, Grayson stands for liberal equality and self-realisation; Jowett for practical, universal state-funded welfare; Snowden for the “virtue” tradition of civic service and social probity. Broady, though, is a cunning novelist: he shuffles the deck and scrambles the categories. We see Jowett, for instance, seduced by the modernist art of Jacob Epstein when he commissions a sculpture as Minister of Works. Walking down Whitehall, this resolutely prosaic social improver was suddenly “seeing everything for the first time”. Dour Snowden gets accustomed to the high life that Grayson — surely the original Champagne Socialist — has always pursued, while the bisexual dandy himself enlists in a New Zealand regiment to serve bravely, and selflessly, on the Western Front.

Ruth Norreys, the actress Grayson married and who bore their daughter, reflects that “He had thousands of selves, and they were all Victor”. Just as the movement he joined did, and does. When he opens a rift within the ILP, Grayson wonders if the party’s executive feared that “he would be storming the conference at the head of an army of theosophists, vegetarians and bottle-throwing Irish dockers, augmented by nonagenarian Chartists, bushy-bearded Whitmanites and a maenad throng of soubrettes and suffragettes”. The 21st-century equivalent of all those tribes, and many others, still fill the Labour ranks today. Not so much a “broad church” (though something called the “Labour Church” did exist) as a crammed and tottering carnival float with its wheels always about to fall off.

But if they don’t: then this ramshackle coalition can still prevail over sleeker vehicles. Lamented in head-shaking frustration by hard-Left ideologues and centrist technocrats, the sheer weird heterogeneity of the Labour clan — which Broady’s novel captures — may be its superpower. But let’s not over-sentimentalise this capacious oddity. Grayson’s biographer David Clark spots a telling likeness between his subject and two other party-splitting Labour superstars: Tony Benn and Oswald Mosley. It’s not impossible to conceive of Grayson, had he not disappeared, eclipsing Mosley on the platform of the British Union of Fascists. The upwardly-mobile Liverpudlian always made an improbable tribune of the plebs. Clark, discussing rumours of aristocratic parentage, reveals that his mother died whispering “the Marlboroughs”. Could Grayson have been an illegitimate relation of Winston Churchill (photos of both men in their twenties look not too dissimilar)?

That’s the subject of another novel, or a TV drama series. In The Night-Soil Men, Fred Jowett muses at Snowden’s funeral that: “The men of the ILP had come and gone and would not be remembered.” Not so: and Broady’s novel should help rekindle their memory. Besides, this ill-assorted gaggle of frenemies bequeathed all their seething contradictions to the successor party that may possibly govern Britain for the next decade. That party’s roots, it turns out, are spicy, gnarled and far from dull. They deserve rediscovery, by both allies and antagonists. Though it seems unlikely that Keir Hardie’s namesake will opt to settle any policy dispute by convening a séance.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe