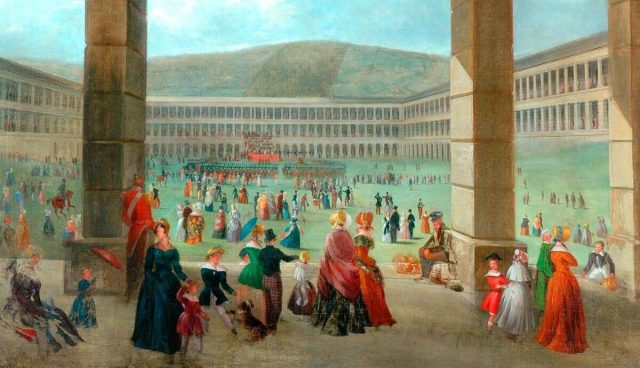

John Wilson’s painting of Piece Hall (Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council)

At some unknown moment in around 9,500 BC, hunter-gatherers in what is now south-east Turkey, and was then lush grasslands rich with pistachio and almond forests, and abundant with sheep and goats, did something for the first time in human history. Seven thousand years before ancient Britons raised Stonehenge, they built a city.

It was small by modern standards, and the site now known as Göbekli Tepe is about two dozen acres. It is a complex of 20 circular compounds and limestone T-shaped pillars richly decorated with pictograms of animals, insects and humanoid figures (some headless) who may be humans — or gods. Alongside the large enclosures huddle smaller domestic structures. For reasons that we will never fully comprehend, our Stone Age ancestors had created the world’s oldest urban settlement. Archaeologists are certain of one thing, however — the site was sacred for the worship of gods and the fulfilment of holy duties.

About 4,000 years later and 400 miles to the south east, the first urban civilisation arrived in the swamps of ancient Mesopotamia. Uruk was probably their first true city. Much about Uruk is also lost to time. But its archaeology, and the ancient Sumerian poem, The Epic of Gilgamesh, both tell a tale in which settlements such as Uruk began life as holy sites created on island mounds in the marshes. Sumerian cites continued to be defined by their temples. People met there to trade, but they came there to pray.

Most urban creation myths have similar patterns. Divine or heroic intervention is localised, enshrined and worshipped. In the process a specific place or an entire city is imbued with sanctity and, via pilgrimage, ritual or festival, the very patterns of travel and trade that boost prosperity are nurtured and encouraged. Ancient Rome had multiple myths. The temple of Saturn was located at the base of the Capitoline Hill (where Saturn was supposed to have founded the pre-Roman city) and also on the edge of the forum. The festival of Lupercalia to secure Rome’s health and fertility was held each February in the holy cave of the Lupercal beneath the Palatine Hill, in which the she-wolf had suckled Romulus and Remus.

Across time and continents, holy cities celebrate the location of a physical interaction between man and god. Jerusalem, which suffers from a surfeit of competing sanctities, is too obvious to discuss. Varanasi in India is where Brahma’s head was dropped into the ground. Lhasa in Tibet literally means “the place of the Gods”. Medieval Europe was bejewelled with shrines deified by a vision of Christ or of the Virgin Mary, or by the births, acts and martyrdoms of Christian saints. Shrines and trade, pilgrimage and travel, were all interwoven just as the sanctity of God and of the city were stitched together.

Sometimes the very process of reconstruction was sacred, as appears to have been the case in the ancient Peruvian city of Caral, with its pyramid temples. Love of place was real not abstract. In 431 BC the Athenian statesman Pericles beseeched his fellow citizens to love their city in his famous funeral oration: “I would have you day by day fix your eyes upon the greatness of Athens, until you become filled with the love of her.” The word for love that he used, eραστά or erastai, was the word for erotic not chaste love.

So far, so ancient — but what do Lhasa or Periclean Athens or Göbekli Tepe have to do with us? Here’s the point. If you regard your towns as places of moral and religious purpose then you don’t just build nice churches, you create better places, more resilient and more beautiful, more worthy of the eternal, not just the here and now. For most of our history hôtels de ville and Rathäuser, town halls and market places, parliaments and public baths, almshouses and hospitals, were built not just to perform a transaction but to elevate our service to each other: a civic temple in the town square, not a featureless box on the ring road.

From Rome’s Baths of Caracalla to Palladio’s Basilica Palladiana in Vincenza, we have historically created our buildings and streets to be as good as we can afford — not as cheap as we can bear. That is why the 500-year-old Fuggerei social housing in Augsburg, Bavaria is better than nearly any social housing built in the last century. That is why until 70 years ago we created places which, today, we visit for the sheer pleasure of being there. Perhaps it is no surprise that one of the world’s most beautiful modern cities, Singapore, has, uniquely among former colonial cities, raised statues to their colonial founder, Sir Stamford Raffles. They are in communion with the past, the better to look to the future.

My favourite example of the (to modern eyes) needlessly magnificent is the glorious Piece Hall in Halifax, Yorkshire. I will never forget the first time I saw it. Emerging through that dark small door into what must, on a sunny day, be one of the most gloriously luminous urban enclosures in Europe, stole away my breath. A quadrangle of delicately Doric arcades behind which 315 merchants’ rooms sat ready for business, a heady mix of souk, forum and fell. What lifts it from the superb to the sublime is the location, the gently sloping topography which results in three arcades to the east and two to the west, with the Pennines rising headily behind. That a building created purely for commercial purposes 240 years ago should be so joyous tells us something important about the culture of our past. Here is the capitalism of the merchant-prince and “civic pride”, not of robber barons and “devil take the hindmost”.

And yet today our towns and our cities, our streets and our squares, are designed to a narrow purpose. They are meant to be efficient and safe; they pay their way; they minimise liabilities. Windows are too high to fall out of, or too small to waste energy; cladding is robust enough to survive the warranty period but never intended to last through the centuries. Generosity is wasteful, stewardship for the naïve. Almost every planning discussion I have descends into a discussion of viability, unit density and efficiency ratios. We live, in short, in utilitarian places. We have lost sight of the fact that while the city has always been a market and a crossroads, a bridge and a city wall, it also used to be a sacred place.

Even though we are richer than ever before in human history, and even though we have at our instantaneous command powers and technologies undreamt of even a century ago, we are somehow conspiring to create places which are less loveable and more perfunctory than would once have been considered civically acceptable. The utilitarian approach to city-making is failing us, creating throw-away places with throw-away meanings. This is bad for the planet, but it’s also bad for us. Create places to last a little longer and we might burn a little less carbon every year. Create places which aspire to, even if they do not achieve, divine beauty, and we may all find the ineluctable hardships of life that much easier to bear.

Empirical research consistently demonstrates that people are happier when they are religious, surrounded by beauty, and intrigued not depressed by their neighbourhood. Meanwhile longevity is plateauing and depression is rising, particularly among the young. In an ironically utilitarian twist, rediscovering the holy in our world would be a good way to help us lead happier and healthier lives. We need to rediscover the language of the sacred city, of creating a place that speaks to our desire for purpose and our innate sense of the divine. Of course, our sacerdotal will not be the same as our forefathers’. More street trees, and less stained-glass I would imagine — less purely Christian, more ecumenical. Less “the faith”, more “faith”. It’s a trick that the British Monarchy have been pulling off for years.

Why don’t we try? For the lives of our fellow citizens, for the re-weaving or our civic life, and for the delicacy with which we tread upon the planet.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe