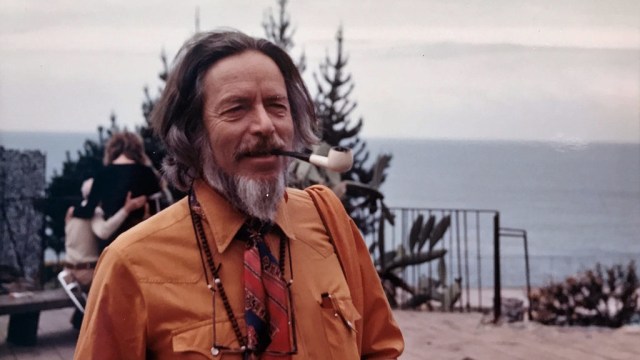

Alan Watts promised liberation. Credit: Alan Watts Organisation.

There is much talk these days of Christianity being doomed: of churches closing, values fading, and community feeling ebbing. But was there ever a time when Christian Britain was one big, cuddly Richard Curtis film?

The New Atheism of the 2000s and early 2010s had serious flaws. And yet Richard Dawkins was surely onto something when he sought to shake religious traditions by their metaphorical lapels and demand that they explain what exactly they are doing when they use religious language. Is it history, proto-science, poetry or something else entirely? For all that Christian commentators enjoyed depicting the likes of Dawkins as wading out into deep theological waters and promptly drowning, this basic question was manifestly a good one — one on which there has long been disagreement among Christians of varying stripes.

This is part of what intrigues me about Paul Kingsnorth’s and Martin Shaw’s conversions to Orthodox Christianity, in both cases via paths that ran through the natural world — Kingsnorth as an environmentalist and one-time Wicca priest, Shaw as a wilderness vigil guide. The two friends claim to be feeling their way towards what they call a “wild Christianity” — which could represent a new turn in our relationship with religion.

Somewhere near the heart of wild Christianity appears to be a powerful sense of numinous presence, within nature and within the Orthodox liturgy, which is at once compelling and strange. In an age of endless cultural recycling, the two men are calling for the cultivation of an attentive silence, in natural surrounds. We have all but lost this ability to listen, but we can re-learn with the help of others: the medieval saints of Ireland, where Kingsnorth now lives, alongside cultures around the world who understand the value of what Shaw calls “putting your great and ancient ear to the dark soil of circumstance and listening”.

The pair are not the first to make the case for a radical, untethered Christianity, free from the trials of institutional religion. In many respects, Kingsnorth reminds me of an English Benedictine monk by the name of Bede Griffiths (1906-1993). His attempt to revitalise Western Christianity, alongside that of the English philosopher and counter-culture guru Alan Watts, who died 50 years ago this month, turned on the question of how language and inner experience shape one another. I suspect that this may end up being true, too, for wild Christianity.

For Watts, as a child, life’s magic could be found in the beauty and fecundity of the family garden — tomatoes and raspberries hanging off vines like “glowing, luscious jewels” — and later in East Asian landscape painting, Zen Buddhism, and yoga. Griffiths, too, was drawn in by nature — in his case, a spiritual awakening one evening on the school playing fields, set off by the sound of birdsong: “Everything… grew still as the sunset faded and the veil of dusk began to cover the earth… I felt inclined to kneel on the ground, as though I had been standing in the presence of an angel.”

Watts and Griffiths regarded the general drabness of mid-20th century Britain as evidence of a fundamental disconnect from life at this deep level: the funereal black suit that Watts’s father wore for work; the “boxy, red-brick quiet-desperation homes” to which Watts saw such men returning home at night.

Unsure what to do about all this, Griffiths and some university friends experimented with living a simple life in a Cotswold cottage: no running water; no technology or literature produced after the 17th century; and candlelit debates about whether, if the village blacksmith could somehow craft an X-ray machine, it would be acceptable to use it.

But Griffiths soon realised that his venture failed to get to the real problem, which was the placing of human beings — and, in particular, a discriminating human intellect — at the heart of reality. Having quit the Cotswolds, he spent a traumatic night of prayer in Bethnal Green, where he found his still-tentative personal philosophy — Christianity with a dash of Eastern wisdom — completely destroyed, as an “abyss” of darkness and unreason overtook him. Out on the street the next morning, London’s buses appeared to “have lost their solidity and [to] be glowing with light”. God, he concluded, had “brought me to my knees, and made me acknowledge my own nothingness… out of that knowledge I had been reborn”.

Watts came to a similar conclusion one evening in his boarding school dormitory, where frustration at his failed practice of yoga and zazen boiled over and he decided to drop both — at which point, quite unexpectedly, “Alan Watts” got dropped instead. Anxious little Alan was, he realised, no more than a case of mistaken identity. The real Alan Watts was part of an immeasurably greater and inextinguishable whole. The release was profound, and its memory never left him.

Watts went on to make a name for himself on America’s West Coast in the Fifties and Sixties, as a gifted communicator of Eastern wisdom — to young Americans especially, often on college campuses — and a progressive thinker on everything from psychotherapy to sex and LSD. For a few years before that, however, he served as an Episcopal priest in America’s Midwest. There, he observed that, unlike in India where Shiva dances and Krishna plays the flute, Midwestern church-goers sit amid heavy courthouse furniture — pews and pulpits — apologising to God, “asking him not to spank” them, praising him in formulae, and engaging in enforced folksiness and “fake joy”. An institutionalised pride is at work here, Watts declared. Everyone talks about grace, but most people want to work for their own salvation — and to see it denied to people who don’t put in the hard yards.

This, he thought, gives rise to a narrow notion of “meaning”: an endlessly deferred happiness. The idea that play might be a more accurate analogy than work for the divine life and our participation in it would, Watts felt sure, strike most congregants as blasphemous. And yet, this was what one of his later LSD trips revealed to him: reality as a giant game of hide-and-seek, with the universe playing at being lots of different things and people. It is not dissimilar to the Taoist philosophy of “flow”, in which reality is akin to breath or water.

Some of Watts’s ecclesiastical colleagues suspected him of being little more than a pantheist with a gift for semantics. And therein lay the challenge. No doubt Watts’s pioneering church services were lots of fun to attend: conversation and jokes, Gregorian chant and piano improvisations, smoking and drinking, sermons capped at 15 minutes. But where was Jesus Christ in all of this? Watts suggested that God is “personal” in the sense of being “immeasurably alive”. Yet wasn’t his image of God just a little too convenient: personal enough to be lively, interesting, and joyous, but not so personal as to make demands of him or censure his behaviour — his “boozing and wenching”, as Watts put it?

Griffiths eventually faced similar questions. Having become a Catholic and a Benedictine in the Thirties, he moved to south India in the mid-Fifties and began to pioneer new forms of monasticism and inter-religious dialogue. He ended up developing a deep fondness and respect for Hinduism, and in particular the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Advaita Vedanta philosophy. His ecumenical work was widely praised and seemed well-suited to the post-colonial era. And yet, asked his critics, was this still Christianity?

Still, Watts’s fanbase seems to renew itself in every generation. Where once they thumbed through his paperbacks on the hippie trail, now they have podcasts and YouTube videos of his talks. Read the comments underneath those videos, and liberation remains the key to his appeal decade after decade.

There is much here that might contribute to a “wild Christianity”: Watts’s warnings about safe, nostalgic religion as a kind of collective clinging; his intuition of a God who is “immeasurably alive”; his self-confessed “rascality”. I’m not sure, however, that liberation by itself is enough. Don’t we soon find ourselves back where we were, and in need of liberation once again? Griffiths, who defined faith as “utter receptivity to the divine”, thought that real liberation was a matter of attentive, committed listening, moving step by step according to what you hear as you go. A Christianity built on that, and capable of generating community from it, is a wild idea indeed.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe