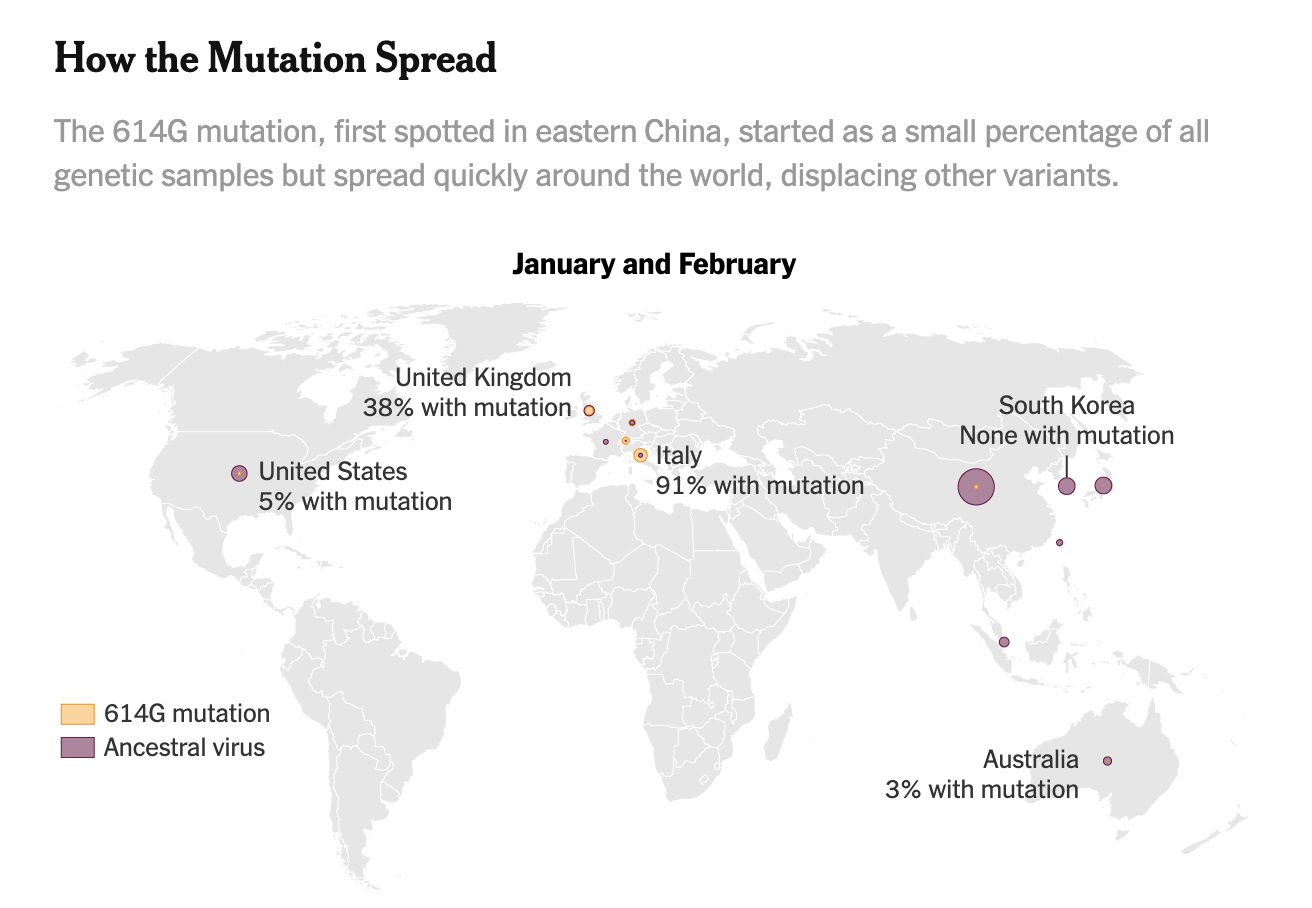

The New York Times recently reported that, in the early months of the pandemic, a particular genetic strain of Covid-19 known as D14G was shown to be more prevalent in Italy than any Asian countries. This may have helped explain why the disease spread so fast in that country, and elsewhere in Europe and America.

Freddie Sayers spoke to David Engelthaler, co-director of the T-Gen Research Institute and former state epidemiologist of Arizona, who has been investigating this idea. His view is that there is now “really compelling evidence” that this strain replicates faster than earlier strains, which “likely” came out of China and through to Europe. “It’s really quickly dominated all of the other strains that were seen in Europe at the time, it became the predominant strain that came into the Americas, spread throughout the United States and is now spread to pretty much every corner of the planet”.

In his own state of Arizona, Engelthaler witnessed several of the early introductions to Arizona, coming from the Pacific coast straight from China, but fizzled out quickly, with less effective transmission. “And then all of a sudden we started having explosive outbreaks. When we go back and look genomically, the vast majority of those cases where we had very large outbreaks were being driven by the strains that were coming from the East Coast out of Europe, which all seemed to have this particular mutation in the spike protein.”

This doesn’t mean that the mutation is more deadly, simply that it may be more faster at transmitting, and therefore it harder to “get our arms around the virus”. As such, Engelthaler argues that trying to eliminate the virus was not the right approach and instead we should have been trying to slow its spread: “What we’re really seeing is a SARS-like infection that spreads like the common cold. And with there’s no way that we could put in mitigation strategies to stop the common cold”.

So were uniform national lockdowns the right solution with this newer mutation that potentially spread more effectively? “As an epidemiologist I think they have has just been devastating in a way that we haven’t even properly appropriately characterised yet”. He says that the “vast majority” of at-risk people “could have been prevented if the focus was on protecting them, rather than on trying to prevent any spread of this virus, which is pretty much is un-containable”.

Engelthaler is also one of the few epidemiologists to have publicly spoken out against school closures, for which there is “no scientific evidence”. “Privately, behind closed doors, there’s definitely been a lot of discussion from the very beginning that there’s no scientific evidence that shutting down schools actually helps to stop a pandemic…Epidemiologists knew that from the beginning, but that was not a popular opinion to take publicly and seems to have been kind of left to the side”.

Ultimately, Engelthaler believes that human agency in the midst of a pandemic has been overemphasised: “I do think that one thing that does seem to get lost in all of this is that there’s a really important factor in this pandemic, and it’s the virus, it’s not just people’s policies and people’s behaviours”. That is especially true when there are “different strains that are acting differently in different parts of the world, leading to different outcomes, at least in some part because of that virus, not just based off of public policies in response, no matter what you do”.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe