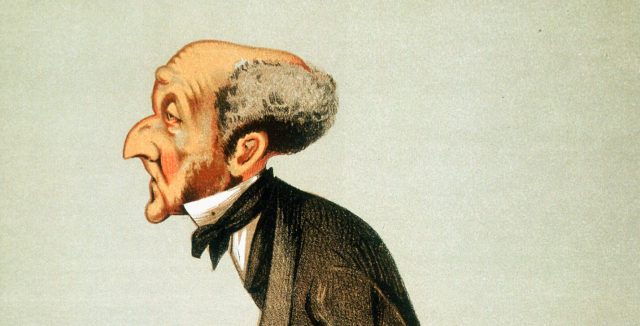

He needed the love of a good woman. (Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

In our age, Victorians don’t stand a chance. Even the most enlightened of them appear to us either as quaint traditionalists (at best) or unforgivable reactionaries (at worst) — snobs, bigots and misogynists, one and all. There is, however, one prominent exception: John Stuart Mill. But for a few quirks, on the 150th anniversary of his death this week, he appears to be a man of our time. And that is in large part thanks to his partner, Harriet Taylor: it was she who made a feminist, even something of a socialist, of him. Better still, she made a human of him.

For Mill, in the tradition of nominative determinism, was once a machine. His precocity is now the stuff of legend: essays on Rome combining historiographical mastery with a recondite vocabulary at age six; trilingual fluency in English, Latin, and Greek by age 12. But it came at a cost. Mill was essentially a lab rat, an educational experiment gone awry. Home-schooled — some may say groomed — by his martinet father, he swallowed whole the utilitarian creed of James Mill: the greatest happiness for the greatest number. But he himself remained a stranger to happiness.

In the younger Mill’s Autobiography, he recalled his father’s “asperities of temper… I thus grew up in the absence of love and in the presence of fear; and many and indelible are the effects of this bringing-up in the stunting of my moral growth.” Public speaking was an insurmountable challenge. He had no self-confidence. Carlyle recorded Mill’s “incapability of laughing”. Aged 17, he followed mechanically in his father’s footsteps, taking up an East India Company job that he held for 35 years. His worldview, likewise, was a carbon copy of his father’s: disdain for unearned privilege in general and the monarchy in particular; respect for the inherent goodness of the middle classes, whose historical role it was to educate the working classes out of their revolting ways; and belief in the superiority of private property over public ownership. All of this he uncritically absorbed and fiercely defended — that is, until he met Harriet Taylor in 1830.

By all accounts, it was a remarkable encounter. Reporting on what transpired, Jane Carlyle observed “that a young Mrs Taylor, tho’ encumbered with a husband and children, had ogled John Mill so successfully that he was desperately in love”. Accustomed to ceaseless cerebration but little else, Mill had been unacquainted with deep emotions. To be sure, he had had crushes before. The Oxford historian Jose Harris writes of the “adolescent tendresse” he had felt for “the dashing Sarah Austin”, translator and wife of the legal philosopher. Mill had later fallen for the musician Eliza Flower. All the same, as one of his friends had it, on the subject “of women, he was a child”.

It was, foremost, an intellectual relationship. Indeed, there is nothing in Mill’s Autobiography to satisfy prurient curiosity. Harriet was drawn less to what Caroline Fox, a mutual friend, described as his “exquisitely chiselled countenance” than his dazzling mind. Her husband John, in Carlyle’s words “an innocent, dull good man”, knew his limitations and was, by the standards of his time, an astonishingly liberal character. Between the married Harriet and Mill, dinner invitations, and later assignations in France, ensued; her husband considerately absented himself, to give the couple the privacy they needed. The affair remained unconsummated. “A Seelenfreundin to both men,” Mill’s biographer Richard Reeves suggests, Harriet stayed “faithful to both men by having sex with neither”. Mill and his mistress — later wife, on John’s passing — were what we would probably call sapiosexuals.

It is possible, Harriet’s biographer Jo Ellen Jacobs surmises, that she had syphilis, which would explain why her second was a childless marriage, though it could well have been the upshot of Mill’s anti-natalism. He posited an inverse relationship between sexual and intellectual appetite, blaming working-class fecundity on their being thick as mince. Mill may have died a virgin. At any rate, none of this prevented the scandal that unfolded upon his marriage, prompting the newlyweds to withdraw completely from society. It was just as well. Isolation breeds intellectual independence, and the Mills’ folie à deux was most certainly a fecund one, intellectually speaking.

Ironically for a child prodigy, Mill’s damascene conversion came rather late in life. Harriet and her partner developed a “collaborative self”. True, the title pages of Principles of Political Economy, On Liberty, and The Subjection of Women carry Mill’s name, but they were very much co-authored enterprises. Her influence is all over these works. Gone were Mill’s Ricardian reassurances about the importance of private property. In its place came the recognition — no surprise to both renters and landlords in Britain today — that “the laws of property have heaped impediments upon some to give advantage to others; they have purposely fostered inequalities and prevented all from starting fair in the race”.

Successive editions of the Principles grew increasingly radical, feeding off both Mill’s mesmerised infatuation with Harriet and morbid fascination with French politics. During the July Revolution of 1830, Mill could be found in Paris singing the Marseillaise at the opera. And during the Spring of 1848, when anti-monarchical sentiment swept Europe, he lamented that England remained eirenic. Robespierre was “the greatest man that ever lived”. The extermination of all those who earned north of £500 a year (he himself earned £600) would be no great loss to humanity.

And so the technocrat embraced populism. That the Commons was “composed of millionaires” did not worry him in the 1830s: what mattered was “not by whom we are governed, but how”. By the 1860s, Harriet’s influence ascendant, his tune had changed: “There can be no parliamentary reform worthy of the name so long as a seat in Parliament is only attainable by rich men.” In the interim, Mill had succumbed to what he would later call his beloved’s “heretical” opinions on the “probable futurity of the labouring classes”. In the wake of the Paris Commune, he called for a cap on inheritance, by which time he had already declared himself in favour of a freeze on rail fares, cooperatives, and greater trade union power — albeit only to “heal the feud between capitalists and labourers”. Gardens and baths could be nationalised, he argued.

Harriet “made me move forward more boldly”, he wrote in his Autobiography, but he stopped short of demanding full-blown statism. John Stuart Mill, Socialist, to quote a recent title, is pushing it. Take his view on democracy. Railing against majoritarian tyranny, Mill betrayed the same technocratic fantasies that plague Remoaner centrists today — ruled by Gina Miller and the perfectly smug Jolyon Maugham. In Considerations on Representative Government, in many senses his weakest effort, Mill makes the case for an enlightened epistocracy: only those who pass a literacy and numeracy test would be eligible to vote. The experts know better. Elsewhere, he wistfully hoped for the day when “the uninstructed” shall show “deference and submission to the authority of the instructed”. Here as well, we see Harriet’s hand. In the 1850s, Mill wrote that he and Harriet were “much less democrats than I had been, because so long as education continues to be so wretchedly imperfect, we dreaded the ignorance and especially the selfishness and brutality of the mass”.

Then there were Mill’s attacks on the polar opposites of the class system, both parasitic: the rentier aristocracy and the lumpenproletariat. The latter, in particular, were singled out for criticism; they were “often very much to blame for bringing themselves into a position in which they require relief”. Worse, they could do with birth control — administered with force: Mill was not averse to using state power to forbid marriages “unless the parties can show that they have the means of supporting a family”, not to mention making welfare cheques contingent on family planning. This was, of course, for their own good. It was because the lower orders bred like rabbits that real wages had been sent plummeting. Harriet had her own reasons for extolling the benefits of smaller families: more children meant more domestic drudgery for women.

Harriet’s guiding hand was more palpably registered in On Liberty. Many of its key ideas, Jo Ellen Jacobs tells us, can be directly traced to her early writings. Today, Mill’s liberalism has become a shorthand for individualism. But as the Oxford philosopher Alan Ryan reminds us, this is a mischaracterisation. On Liberty combines both a “positive” and a “negative” idea of liberty, but it is only the latter it is known for. This is the gospel of toleration: live and let live (so long as it doesn’t harm others). Verging perilously close to the autobiographical, practically telling on his own dangerous liaison, Mill castigates the American intolerance for Mormon polygamy. Prostitution and gambling, too, ought to be tolerated, he argued. But his relationship with Harriet was equally to be felt in Mill’s “positive” conception of liberty. Here is the communitarian, as opposed to individualist, strain in his thinking. Mill expected the bourgeoisie to show leadership, working for the greater social good on the behalf of the working class that looked up to it.

More than shaping his views on equality and liberty, Harriet above all won Mill over to female suffrage. Indeed, his reputation as an apostle of gender equality in great measure rests on her interventions. Mill’s father, it should be remembered, had concluded in his Essay on Government that women’s interests were essentially the same as those of their fathers and husbands; extending the vote to them was essentially superfluous. The younger Mill’s progress, acutely shepherded by Harriet, led him to question the wisdom of this line of thought. He may have been an incorrigible bore — and Stefan Collini is on to something when he observes that a compendium of Mill’s wit would be “a slim one indeed” — but we owe one of the better ripostes to the votaries of the male franchise to him: excluding women was about as absurd as denying the vote to redheads.

Mill also made an early foray into the pronoun wars, replacing “his” with “their” in the third edition of the Principles, at Harriet’s instigation. In The Subjection of Women, he challenged the institution of marriage, for depriving women of the rights to property, inheritance, and divorce. In 1867, Mill introduced the first bill proposing suffrage for women in the Commons. He died in Avignon five years later, leaving half his estate to promote women’s education.

Mill may have started his intellectual journey as a utilitarian, but he ended it, more than anything else, as a utopian. And it was that restless font of reform, Harriet Taylor, who was responsible for this. Her brilliance and ebullience were, undoubtedly, very infectious. But I wonder if they might have got carried away, putting so much store in Progress. British society evidently was less Millian than they imagined. They felt sure, for example, that Britain was to be “republicanised … before we die”. There is some irony, then, that the 150th anniversary of Mill’s death will find the country not only not republicanised but in the mad throes of coronation hysteria.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe