If you are wearying of lobby journalists’ efforts to manufacture ‘gotcha’ political moments in the midst of a pandemic, or dizzied by our post-truth era of spin and internet gossip, dive into Apollo magazine’s beautiful long read on the ‘pre-truth’ era of Restoration royal portraiture.

The piece examines the political and cultural undercurrents at play in these enormously expensive and influential works of art, which functioned as interventions in the public image-making of prominent political figures.

The 17th century English court, reeling from the horrors of the Civil War, was forced to contend not just with an unstable political and religious environment but also with the mercurial and highly-sexed monarch, Charles II. His numerous ‘official’ mistresses muddied the political waters in ways that made them both seductive and also widely loathed. Several used their position to become influential power-brokers, operating as unofficial access points to royal attention and favour and even taking money in exchange for boosting courtiers to ministerial roles.

Their haters had to write anonymously, for example via coded verse, but their lampoons spread like wildfire. The mistresses, in turn, retaliated with portraiture, the PR of its day.

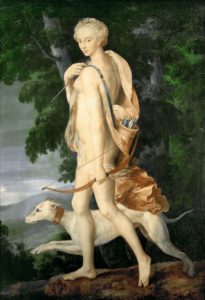

While lords and kings were painted in the ‘historical grand style’ that linked their actions to poetic, Biblical or classical tropes, only seriously powerful women — such as royal mistresses — were depicted thus. These portraits were ‘an efficient means of projecting an image of power, and […] implied that their subjects were people who could live up to the grandeur and ambition of the genre.’

During her affair with the king, the Italian Duchess of Mazarin had herself painted as Diana, Goddess of the Hunt. The Duchess of Cleveland, another royal mistress, had herself depicted as St Catherine of Alexandria. The latter portrait was deliberately provocative, as St Catherine was tortured and beheaded for refusing to surrender her virginity to the 4th century emperor Maxentius. Not content with having herself painted as a virginal martyr, Cleveland went on to commission a painting of herself as the Madonna herself, cradling her illegitimate son Charles Fitzroy. This was, in the context of its time, a particularly epic troll:

The author captures a flavour of the ferocious interplay between the manufacture of public image via official portraiture and poetry, and its hostile subversion via ‘lampoons’ and critical verse, often scabrous and cruel on a level that would startle even those inured to social media pile-ons:

A political environment divided between expensive official image manufacture and vicious, often anonymous critical point and counterpoint by drawing on a store of cultural memes to spin the discourse. It sounds familiar. It is tempting to wonder whether, far from representing a high point of cultural progress from which we have now declined, the era of supposedly objective and rational political discourse was in fact more of a flash in the pan.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe