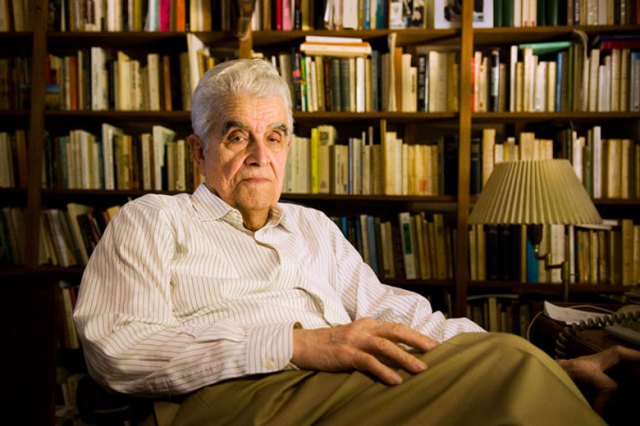

We’re all doomed. Credit: Stanford University.

“The apocalypse,” declared René Girard, “has already begun.” The most influential philosopher in the world today was on a messianic mission before his death seven years ago.

Since then, his work has found acclaim far beyond the academy: business gurus, political pundits and Twitter personalities invoke his social theory — and particularly his account of the ‘mimetic’ origins of desire — to explain an ever-widening array of phenomena. But if his ideas are increasingly popular, their roots are usually ignored.

Girard meant his ideas to serve a religious purpose. He claimed in one of his final books, published in English as Battling to the End (2010), that his work had “been written from a Christian perspective”, and specifically a Catholic one. He was not, however, a cultural conservative trying to offer a defence of traditional Christian morality. While his theory of desire is inseparable from his belief in Christianity as the true faith, it is also tied to a radical perspective: one in which the end times foretold in the New Testament are upon us.

Girard’s theory of desire, separated from its Christian context and purposes, is appealingly counter-intuitive and expansive. It offers the intellectual pleasure of over-turning (perhaps a bit too readily) what is said to be conventional wisdom, and of reducing apparently distinct processes to a single causal mechanism.

According to Girard, we commonly misunderstand individuals as pursuing pre-determined aims common to all human beings — like sex or status. These desires, we assume, are satisfied by what we manage to attain. In fact, Girard argues, our desires arise not so much from such natural drives as from a universal tendency to envy and emulate other people, which orients us to seek out whatever our rivals (that is, everyone else) are seeking. We want what we want because other people want it.

Girard saw imitation not only as a fundamental social process, but also as a source of violence that, if unchecked, might unravel society. This is, in some ways, an ancient insight. The poet Hesiod, at the dawn of Greek literature, observed that strife can lead us to imitate and surpass the achievements of our neighbours in socially beneficial cycles of competition — or it can lead to envious rage and violence. In the eighteenth century, the founders of laissez-faire economic thought argued that what they called “emulation”, copying our rivals’ behaviour with the aim of outdoing their success, was the basis of economic growth, but also a source of conflict among individuals and nations.

The originality of Girard’s thinking lies in his argument that societies manage the ambivalence of imitation — its capacity to promote social cohesion or to degenerate into spirals of competitive violence — through “scapegoating”, or the exclusion of some agent identified with imitation’s negative aspects. In his account, scapegoating is a function of religion, and takes the form of sacrifice, the physical destruction of some victim who was understood as responsible for, or in their innocence expiating the sin of, dangerous imitation. The violence of sacrifice precludes the violence of mimetic desire.

Girard has found posthumous popularity in Silicon Valley circles — most prominently with Peter Thiel. The historian and philosopher Justin E.H. Smith has written a particularly sharp critique of the way would-be finance and technology gurus use Girard to give a veneer of sophistication to otherwise trivial observations about trends. But Girard intended his theory not to provide bite-sized insights for the business world, but to serve a specific, religious purpose as a justification for Christianity.

According to Girard, the death and resurrection of Christ had freed humanity from the cycle of potentially destructive imitation that scapegoating had been intended to contain. The message of the Gospel was that a perfect man, without any violence in him, had offered himself as the final sacrifice — and as a model for all future imitation. In his death, Christ abolished the need for further scapegoats. In his life, he provided an example for followers — an example that, unlike all previous objects of imitation, could produce no envy or aggression but only love and peace.

For Girard, Christianity is the end of “religion”. In the traditional sense, “religion” had always meant a system of rules and procedures for containing the violence of mimetic competition and maintaining social order through rituals of sacrifice. Only Christ, Girard argues, offers an escape from these systems.

Unfortunately, for most of the history of Christianity, the radical message of the Gospel was suppressed by the Church. Ever since the late Roman Empire, ecclesiastical leaders worked with politicians to prop up social hierarchies and justify inequality. Christianity was presented as another version of ancient religions, in which priests accepted payment from congregations in return for rituals of blessing and sacrifice. The Church fulfilled the role of what Girard, drawing on an obscure term from the theology of eschatology, calls the katechon, a force that holds back the return of Christ and the destruction of our world.

This is a Protestant vision of religious history. It views the Catholic Church and its compromises — first with the Roman Empire, then with all subsequent political authorities — as an occlusion of the true message of Christianity. But for Girard, a Catholic, this was not a betrayal, but rather a necessary stage in a historical process that is finally coming to an end.

In Girard’s vision of history, the secularisation of the West — the decline of the political role of religion, and of religious belief — means, in an apparent paradox, that the Gospel can, for the first time, “become clear”. For centuries, our societies had existed on the basis of a usually unspoken, and philosophically incoherent, compromise between pre-Christian values (of preserving society through rituals of sacrifice) and the message of Christ, who showed that sacrifice is now unnecessary and that the end of the world is at hand.

Secularisation dissolves this compromise. It hastens the apocalypse, and thus the second coming of Christ, by ending the social rituals that had constrained the violence of competition: “all that remains is mimetic rivalry, and it escalates to extremes.” A society without religion, ritual, constraint, or limit, in which atomised individuals compete with each other in steadily worsening spirals of envy and hostility, is the clearing in which Christ will reappear.

Pundits discussing the mimetic aspects of media trends or the role of “scapegoating” in cancel culture use Girard’s concepts to explain a world that he insisted is on the verge of perishing. Those who critique Girard’s ideas make a similar mistake to those who wish to take them up for political purposes. Justin E.H. Smith, for example, condemns “the Girardian version of Catholicism as a clerical institution ideally suited to the newly emerging techno-feudalist order” promoted by Thiel. But Girard argued that the role of the Church as a “clerical institution” is coming to an end, as its long compromise with politics ceases — and that this is both a terrifying and joyous event.

His apocalypticism may be disturbing, or indeed mad, but it is not compatible with conservatism — or even with politics as such. Girard is not merely a source of stimulating or useful ideas for Silicon Valley. He is a messianic man of faith, for whom the decline of religion, and of the West, makes straight the way of the Lord.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe