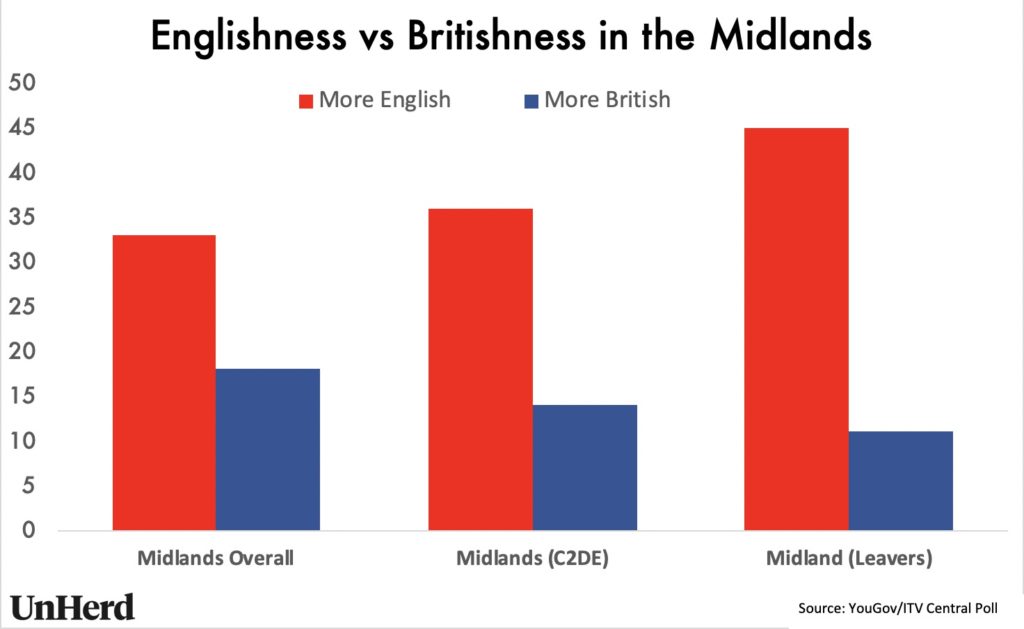

A YouGov poll for ITV Central has found that people across the Midlands are more likely to identify as English than as British.

In the poll, which covered the East Midlands and West Midlands regions, 33% considered themselves more English than British, and only 18% the opposite.

The sense of Englishness was heightened among those who voted for Brexit (45% more English versus 11% more British) and within the C2DE (mainly working-class) social group (36% versus 14%).

Liberal commentators would have us believe that this swelling perception of English identity is a threat, causing some to prophesy a return to the 1930s if it isn’t checked. But, as with other of the nationalist movements that have emerged in Europe over recent years (and, in truth, the rising sense of Englishness can hardly be described as a movement), it has nothing in common with the virulent, aggressive, expansive nationalism we saw back then, and has its roots instead in a feeling of alienation and neglect, a desire among a buffeted and disorientated populace to protect what they have (or once had). To misidentify it in this way will only serve to strengthen it.

It’s about representation. The disaffected English look towards the other nations of the UK and see that voters in these places have major political parties and democratic institutions willing to speak for and represent them exclusively, whereas those who wield the greatest influence over the political and cultural life of their own country — primarily liberal graduates — positively eschew any notions of English patriotism or Englishness. So, unsurprisingly, the working-class English in the provinces react.

The more removed from the political and cultural establishment the English feel, the more determinedly English they become. Politicians across the piece, so far as they have taken any interest in it at all, have not understood this phenomenon. That’s because increasingly few of them have any true understanding of the lives of those who are its main drivers.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe