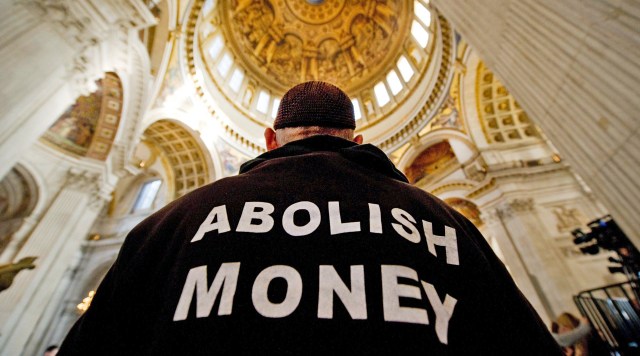

A protester stands beneath the dome inside St Paul’s Cathedral in London, on October 28, 2011. AFP PHOTO/LEON NEAL (Photo credit should read LEON NEAL/AFP via Getty Images)

A few days before Ori Brafman flew over to Virginia at the invitation of the US Army, he was sitting on a lawn in northern California, soaking up the vibe, wearing not much more than a fluffy pink fur throw. A vegan, and a peace studies major at that bastion of progressive values, Berkeley University, Brafman wondered what he would have in common with the man he was about to meet – a man who, a few years later, was to become the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under President Obama, and one of the central guiding figures of the war on terror, General Martin Dempsey. What on earth could the General want with someone like Brafman?

Back in 2006, Brafman had co-authored a popular book on organisational structures, The Starfish and the Spider, in which he compared the difference between biological organisms like the spider, which have a small head that controls its body, and the much stranger organisms, like the starfish, that don’t have a centralised structure but whose limbs can regenerate, even when severed from the main body. Chop off the spider’s head and the spider is dead. But the starfish doesn’t have a head and many of its functions have been decentralised, allowing it to keep going even when a major part of it has been cut off.

It turns out that the US Army was much taken with the spider and the starfish as metaphors for different organisational structures, mainly because of the trouble they were having with ISIS. The Army was a spider, with a strong command and control structure, while many terrorist organisations were radically decentralised, specifically designed to avoid infiltration or decapitation. And it worked – they were proving extremely difficult to destroy.

Writing a thesis at the US Military Academy at West Point a few years later, Major Luciano Picco explained why the US Army was having such trouble dealing with the starfish way of doing things.

“Due to a long history of success by embracing the hierarchical structure,” he wrote: “indications are that as a whole, the Army has a hard time conceptualising the decentralised ideas presented by Mission Command and inculcating those notions throughout the Army.”

But it wasn’t just the Army that was getting interested in Brafman’s ideas. Ten years ago this month the Occupy movement first arrived at Zuccotti Park in New York’s financial district, proclaiming the slogan “We are the 99%”.

But it wasn’t just the message that was radical, it was also the way they organised themselves — the fact that there didn’t seem to be anyone “in charge”. Despite the need of the media to isolate leaders around whom to tell the story of a movement, Occupy operated on starfish principles. It was held together not by some central leadership group, but by a shared sense of conviction. Policies would not be handed down from a central committee, but would emerge from assemblies of the faithful.

This was a real headache for those tasked with negotiating with the protesters. When I was involved with the dispute between Occupy and St Paul’s Cathedral, it was clear that the City of London authorities, the Police and the Cathedral couldn’t quite understand what they were up against.

Their instinct was to approach Occupy with the familiar request “take me to your leader” — after which they would negotiate with them and perhaps strike some sort of deal. But there wasn’t a leader, and because of this the authorities had little idea what to do. From the Occupy perspective this meant there was no one who could sell them out, no central figure(s) who could be discredited or strong-armed into compromise. The spider had no idea how to deal with the starfish.

The police eventually cleared the Occupy camp at St Paul’s in February 2012, evicting the protestors. But that was not the last that the police saw of these faces. Over the years, many of the same people who were there went on to help set up Extinction Rebellion and were also influential in other protest movements like Black Lives Matter.

The aims morphed and adapted, and new limbs to the protest movement were grown – ideas were “emergent”, to use the organisational jargon. You cannot evict an idea. And this model is not just a feature of the Left. The Tea Party movement was just as horizontally organised. After all, who was its leader? It’s hard to say. Does it even matter?

Unfortunately, the Church of England learned very little from its encounter with Occupy. Just this week it was unveiling a new plan for its future organisational structure, and it is a doubling down on the whole centralising tendency that has been going on for the last 30 or so years. Just as protest movements were out there “taking the knee”, Church leaders were poring over their spread-sheets and flow charts.

Organisationally, the Church of England is a mess of overlapping and competing powers — bishops, synods, councils, pension boards, parliament, parishes — which is a real irritation to the pathologically tidy-minded. Formed as a shotgun marriage between two very different, perhaps incommensurable, approaches to religious authority — the Catholic and the Protestant — it’s little wonder the Church of England is an organisational hotchpotch.

Calling for greater “clarity”, this new plan announces that there is a “considerable confusion… about decision-making authority, a lack of understanding about which decisions different bodies are empowered to make and how those decisions are reached.”

So this review proposes a new body to take over most of the central functions of the Church. And inevitably it has an organisational flow chart and an acronym CENS – the Church of England National Services. Now there’s a rallying point to stir the blood and drop the faithful to their knees in wonder!

It’s as if the Church has decided to invest in Blockbuster Videos just as everyone else is switching to Netflix. All over the world, decentralised systems are on the ascendency. The Taliban have seen off the US Army. Blockchain technology has allowed radically decentralised crypto currencies like Bitcoin to flourish. eBay may have a CEO, but its real power lies in the millions on mini-encounters between buyers and sellers.

As Brafman observes in a more recent book, The Chaos Imperative, it is often from the edge of human networks that the serendipitous encounters driving innovation and creativity take place. In Church terms, these edges are called parishes — often small, semi-independent pockets of half-organised goodness, spreading out into their communities rhizomatically.

On this traditional model, the bishop is not primarily a leader or a manager. He or she is concerned with the promulgation of doctrine, renewing the core message with inspiration, and the care of the clergy — a vicar to the vicars. These days, unfortunately, we have too often dulled their spirit by locking them in committees and chaining them to laptops to write bloodless reports. And the parishes are becoming sucked into this whole top-down managerialism led by bishops who go on leadership courses and do half-baked MBAs. God save us from people with MBAs.

What Brafman maintains is that the crucial thing keeping inherently messy organisations together is a belief in the cause. They don’t even need better management flow charts, they don’t need more command and control – often less of it – they need better preachers. And the Holy Spirit has no need of acronyms.

The Church is becoming more spider-like just as everyone else is learning the power of being more like a starfish.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe