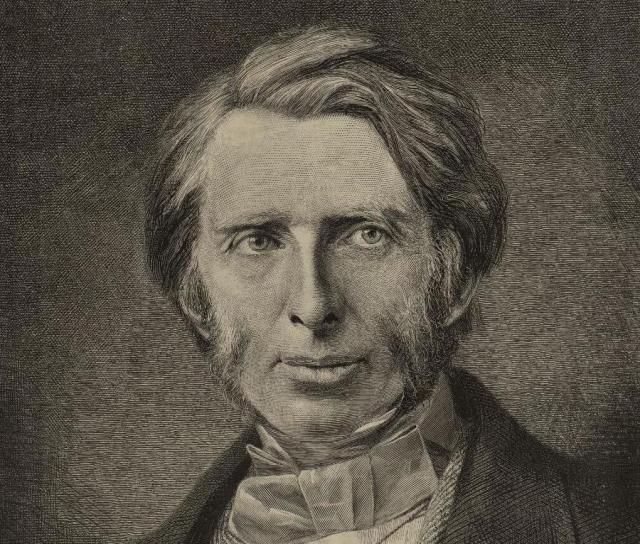

For decades, the fame of John Ruskin, eminent Victorian, was discernible mostly in the inordinate number of his works in second hand bookshops. He never quite fell into obscurity though: there is an art college he established in Oxford, another for working men; a museum in Sheffield for metal workers, maintained by the Guild of St George for the education of workers.

Indirectly his influence survives in the National Trust whose founders were profoundly influenced by him. And in the lingering aesthetics of the Arts and Crafts movement. He was an important influence on Gandhi.

But now, with the bicentenary of his birth, there’s increased interest in his ideas – a sense that Ruskin’s time has returned. There’s an exhibition from his Sheffield museum at 2 Temple Place in London, The Art of Seeing, to be followed by a series of others over the year. One of the most interesting will be in York, about his influence on modern ecology. Ruskin was one of the first to observe the effects of industrial pollution on clouds. If he were around now, he’d be a David Attenborough figure: campaigner, castigator and national treasure.

So who was Ruskin? He was an art critic, the champion of the Pre Raphaelites, the defender of Turner, the great advocate of the Gothic style of architecture. But he was way more than that: he was a moral art critic, which is to say he thought of art as being expressive of the moral character of a nation rather than anything merely ornamental (though he set great store by ornament).

He was a social reformer, who believed passionately in the dignity of good work and the importance of beauty in the life of all classes. He was a conservationist (though he could rarely see a medieval manuscript without wanting to dismember it to show off the pictures) and was one of the first to identify clumsy restoration – in Venice – as a danger. One of the amusing bits of the London exhibition is a display entitled 15 Things Heartily Loathed by John Ruskin – he was a very good hater – and they ranged from A Railway Station to Palladio (the great classical architect) to Making Money.

His influence was colossal, much of it disseminated by himself in lectures given to working men’s societies from Tunbridge Wells to Sunderland; printed, they got everywhere, but they still have the flavour of the lecture room, as when he thanks his audience for turning out on a rainy night. “There is”, he felt, “only one cure for public distress, and that is public education, directed to make men thoughtful, merciful and just.” But his lectures were as likely to be about Titian or Turner as about the use of ironwork or reading, or the importance of sculpture in architecture.

In many ways, his time has come: his holistic view of art and architecture, as being expressive of a good society – the Gothic style, he felt, was great not just because it was based on nature but because it was the work of “thoughtful and happy men” – has an awful lot to say to our own day.

Recently, the think tank Policy Exchange launched a Building More, Building Beautiful campaign to make public architecture more beautiful and more acceptable to the public. That was a very Ruskinesque endeavour. At the very beginning of The Seven Lamps of Architecture, he declares that “Architecture is the art which so disposes and adorns the edifices raised by man for whatsoever uses, that the sight of them contributes to his mental health, power and pleasure”.

He emphasised in his lectures to architects that people cannot help but look at their buildings so they must be made as well as possible. That link between good public buildings, public space and mental health is very much of our time; in fact, it’s prophetic. And the moral responsibility that architects have in creating or destroying the beauty of the built environment, which others have no choice but to look at and live with, was never more strongly put than by Ruskin.

His critique of society is also relevant. Take the concept of fast fashion: inexpensive clothes that date within months or weeks and are replaced in short order by new clothes that are equally cheap, in a never-ending round of consumption. What thoughtful millennials are questioning is how those clothes are produced: for instance, when it transpired that the Comic Relief Spice Girls T-shirts were produced by workers paid 35p an hour there was outrage; well, that is exactly what would have riled Ruskin. Or take the H&M blouse I wore to the launch of his exhibition: a leaf design by William Morris made with synthetic fabric in China.

It was cheap, presumably to keep ahead of the retailer’s competitors and will, in the case of most wearers, be thrown away within the year. Ruskin was a close associate of Morris, who created the design, but he would have taken instant exception to the way that a natural design was printed on an unnatural fabric by workers whose conditions were almost certainly less attractive than those of workers here, let alone the ideal of manufacturing conditions he described in his late work on social reform, Unto This Last:

“Supposing the master of a manufactory saw it right, or were by any chance obliged, to place his own son in the position of an ordinary workman; as he would then treat his son, he is bound always to treat every one of his men…”

In other words, the design would have been diminished for him by the mode of production and by the throwaway clothes culture it’s part of.

Ruskin was born into an evangelical Protestant family – his mother made him learn the Bible by heart – and he had, in many ways, the aspect of an Old Testament prophet; he used the prophets to castigate those he thought were living lives of thoughtless vanity at the expense of the poor.

Even after he discarded his evangelical beliefs (though he would return to broad Christianity), he would invoke Isaiah and the gospels to challenge his audience. In his lectures on domestic architecture, he recommended that houses should be built with porches with little benches inside: cheerfully admitting that homeless people might take shelter in them, quoting Isaiah about giving aid to the poor “in thy house”.

In one passionate passage in Sesame and Lilies in which he quoted an inquest into the death of a boot repair man who died of hunger and cold while trying to earn a living, he printed the account in red, saying: “be sure the facts themselves are written in that colour, in a book which we shall all of us…have to read our page of, some day.”

He would lecture on the inequality and rampant poverty so common to the industrial capitalist age in which he lived, and which resonates so strongly today. He castigated the exploitation of the poor; he suggested reform.

Despite such strong political views, it was as an art and architecture critic that he was best known, and there is no one now whose views on these subjects represent so coherent a worldview: if he loved Turner, he detested Constable; if he passionately recommended the Gothic, he passionately denigrated the classical as unnatural and inhuman. Cardinal Newman was one who thought this too sweeping: what he mused, was actually wrong about domes? But Ruskin’s philosophy was all of a piece: he felt that architecture based on nature is fundamentally sound, that art and architecture should be premised on honest and good workmanship, that we are all better for beauty in our environment: natural and built.

And he was as zealous for the natural environment as for the built; contact with the natural world was essential not just for art but for human flourishing. In his day it was industrialisation that despoiled the environment as well as thoughtless development. That gave his one and only fairy story, The King of the Golden River, the character of a fable. In it two bad brothers, Hans and Schwartz are brutal to people and animals and nature; their good, downtrodden brother, Gluck, is kindly to other creatures and people and respectful of nature. They get their just deserts.

That aspect of the tale has been captured in a new edition of the story by Quentin Blake who provides new colour illustrations. In the preface he says, “I soon became aware of two remarkable things about Ruskin’s story. One is that, in writing this children’s story, he had also written an eloquent parable of his own view of nature; or, as we might say, the environment. Second, that despite Ruskin’s efforts, the fable is even more relevant today…There are plenty of Hanses and Shwartzes [the baddies] operating globally; pray heaven that any contemporary Gluck may have the good fortune of his young predecessor.”

Ruskin not only anticipated most of our contemporary social and environmental concerns; he expressed them far more eloquently than we do. He was a prophet, not just in the sense of foretelling doom but in drawing attention to our moral failings. As he said in Unto This Last: “That country is the richest which nourishes the greatest number of noble and happy human beings; that man is richest who, having perfected the functions of his own life to the utmost, has also the widest helpful influence, both personal, and by means of his possessions, over the lives of others.” He was of his time and ahead of it. Those books of his which were for decades so little read, it’s time to read them again

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe