In March 1968, American forces entered the Vietnamese village of My Lai. One of the soldiers who was there that day initially misinterpreted his orders. He’d been left in charge of a group of women and children and told, “You know what to do.” He thought he was being asked to keep an eye on them. A few minutes later, his lieutenant came back and asked why the villagers were still alive.

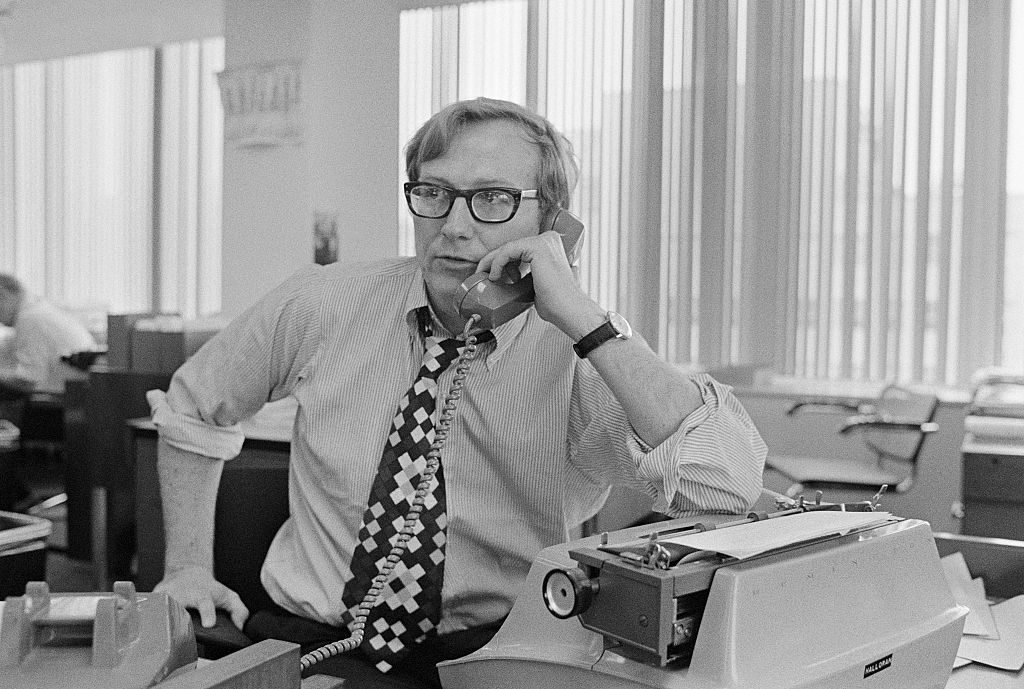

Months later, whispers of the massacre reached a freelance reporter named Seymour Hersh, who’d previously covered the Pentagon for the Associated Press. He went back to his old stomping grounds, and an aide to US Army Chief of Staff William Westmoreland let something slip. In an attempt to blow Hersh off, the aide said, “this guy Calley” can “go to hell”. Now Hersh had a name.

This is a key moment in the new Netflix documentary Cover-Up, directed by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus. Cover-Up chronicles Hersh’s long and strange journalistic career, which includes not just breaking the story of the My Lai massacre but reporting the torture of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib in 2004, and competing with Woodward and Bernstein to uncover new aspects of the Watergate scandal in 1973.

It’s not hagiography. The documentary shows us Hersh’s flaws, and his tangible discomfort with introspection about those flaws. In recent years, he has at times published dubious stories on his Substack without subjecting them to the level of source verification that editors at institutions such as the AP, The New Yorker, or The New York Times would have required when he worked there earlier in his career. It also lingers on what Hersh himself would now acknowledge as the worst moral and journalistic failing of that career, when he let himself be taken in by dictator Bashar al-Assad’s denial of the regime’s atrocities during the Syrian Civil War.

Whatever one makes of the balance sheet of Hersh’s career, though, the bigger question is why new Seymour Hershes seem to be in such short supply. It’s impossible to watch Cover-Up without a visceral sense of why we so badly need investigative journalists with his combination of tenacity and moral fire to expose official wrongdoing.

The incentives working against media institutions cultivating new Hershes are considerable. To begin with, when publications run the kind of stories Hersh has spent his life bringing to light, they risk legal liability or ruining relationships with quotable officials. The public may have a right to know what governments do in the dark, but some portion of the public is always going to be angry about being told. When Lt. Calley was finally put on trial and convicted, a novelty song called “The Battle Hymn of Lt. Calley” exploded in popularity. Set to the tune of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”, the lyrics portrayed him as a heroic soldier who was stabbed in the back. The song made no mention of the rapes at My Lai, the women Calley and his comrades killed for refusing to remove their clothes, or the babies he shot at point-blank range.

All of these disincentives for investigative journalism were in place in the Seventies. Indeed, Hersh left the Times in 1979, after years of frustration with the Paper of Record’s squeamishness about breaking the kind of stories he wanted to report. In 2025, there are new obstacles stemming from the economic decline of mass media. There are far fewer stable full-time journalism jobs of any kind to go around, and magazines and newspapers are less likely to be able to offer a substantial budget to support investigative reporting. It all adds up to a recipe for more stenographers and fewer investigators. And the army of influencers who pride themselves on their “independence” are very much part of the problem. They can form their own opinions but they entirely rely on information reported by others.

Meanwhile, any new Hershes who are incubating right now are all too likely to end up joining him on Substack. Few will have the financial resources to crisscross the country or the world following leads, and many may fall into some of the same mistakes as late-career Hersh.

This is grim news for American democracy. No matter how much freedom ordinary citizens have, they won’t be able to decide whether they approve of their government’s actions or whether they want a change if they never find out what the Army or the CIA are up to in the first place. Some, of course, will be angry about finding out. But that doesn’t make telling them any less vital.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe