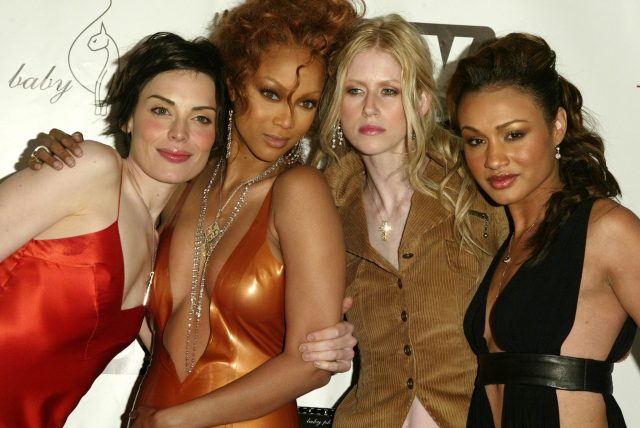

The cruelty of ANTM was always the point. (Credit: Christopher Polk / Getty Images)

My first job in journalism was at a knitting magazine. That meant I was involved in planning photoshoots, and planning photoshoots meant discussing the models. Trust me when I say there are no good memories attached to those conversations. Huddled with my colleagues, we would flick through a human catalogue of portfolios and scrutinise each woman’s shape and face in terms that, even then, I’d have been ashamed for the subjects to overhear.

I didn’t feel particularly bad, though, because I didn’t respect models. How was being pretty and standing still a real job? This was 2008. The supermodel era, with all its absurdity and magnificence, was over. Big-haired glamazons had been replaced by malnourished, wall-eyed teenagers. And in terms of news (and industry) value, models had been deposed by reality stars and other tabloid darlings. High fashion still needed the catwalk, but for the mass market, fortuitous placement in a paparazzi shot was worth more than anything.

There was one woman who caught this vibe shift. In the 2000s and the 2010s, she would be synonymous with the concept of modelling — in fact, she was probably the most famous model in the world in that era. The last supermodel standing. But by then, she was retired from the fashion industry, and though the public still identified her with her past career, she was in a new business now: the reality TV one. She was Tyra Banks, and the show she produced and fronted was America’s Next Top Model (ANTM), which ran from 2003 to 2018.

The format seems obvious now, because it established the template for so much reality TV to follow. The first “cycle” followed 10 young women who aspired to become, per the title, America’s next top model. Week by week, they received coaching from industry experts and were put through challenges that, supposedly, prepared them for the travails of the fashion industry. At the end of each episode, a panel of four judges would assess the contestants’ performance: whoever was considered the weakest would be dispatched from the competition.

The girls lived together in an apartment, with cameras on them at all times. This was a high price to pay for admission, but then the prize seemed worth it. The winner would walk away with a modelling agency contract, a magazine shoot and a deal to represent a cosmetics brand — and though the agency, the magazine and the brand would all change over the course of the show’s existence, this remained broadly the same for the entire run. This was, in theory, a golden ticket.

Importantly, it was a golden ticket that was within reach even if you didn’t match the conventional image of a model. In her early career — long before she reached the heady heights of being the first black woman on the cover of Sports Illustrated’s prestigious annual “swimsuit edition” — Banks had been forced to beat the streets from audition to audition in order to secure bookings, and often faced rejection because she was black. Part of the pitch for ANTM was that it would diversify the narrow aesthetics of fashion.

Now, because this is the cycle of content for anything that was popular in the Noughties, ANTM has received the “reckoning” treatment, in the form of a three-part Netflix documentary called Reality Check: Inside America’s Next Top Model. In it, we learn that the girls who competed were viciously body-shamed; one clip shows “runway coach” J. Alexander conducting a weigh-in of contestants while wearing a shirt printed with the slogan “don’t feed the models”. The models suffered dangerous, painful and absurd conditions in the challenges (one contestant was hospitalised with hypothermia after a shoot in a pool). The show blacked up contestants for ethnicity-swap challenges — not just once, but repeatedly.

Keenyah Hill, who competed in cycle four (2005), recounts how she was sexually harassed on-set by a male model during a photo shoot. But the most devastating story belongs to Shandi Sullivan of cycle two (2004). On a trip to Milan, she was paired with a male moped driver for a day of castings. At the end of the day, the producers invited the drivers to drink with the contestants. Sullivan, who hadn’t eaten all day, blacked out; when she came to, her driver was having sex with her. It sounds, and looks like an assault, but it was broadcast in an episode called “The Girl Who Cheated”.

All this is horrifying, but none of it is new: every one of ANTM’s missteps was filmed, edited and put on air. The framing of the Netflix documentary is that, during lockdown, a whole new, and younger, audience discovered the show. The backlash came fast: Banks was accused of normalising blackface, enforcing racist tropes and emotional torture. It’s also true that many past contestants have now gone on the record to talk about their experiences on the sharp end of reality: obviously, it is significant for Sullivan to tell her story in the documentary.

The phrase “in plain sight” comes up a lot in reckonings with the sins of Noughties media. In Channel 4’s 2023 Dispatches on Russell Brand, much was made of the way his sexually explicit comic persona mirrored the allegations of sexual assault against him. (Brand is currently awaiting trial on multiple charges including rape, which he denies.) In 2021, when Britney Spears’s conservatorship hearings revealed the level of control she was placed under by her father, much commentary pointed out that her public behaviour had always been at odds with the narrative of her as a happy performer who had recovered in the care of her family.

Nonetheless, both those cases — and others like them — relied on information that had never previously been available to the public. In the case of ANTM, almost everything that people are appalled by was right there on the screen all along. The show did not conceal its cruelty. The incident in which two contestants were forced to go through extensive cosmetic dentistry or be thrown out of the contest was a narrative arc, not a shameful secret. The bloody extractions and drilling, the painful application of veneers, happened on-screen.

The cruelty of ANTM was always the point. The show’s most iconic moments were all, ultimately, ones of humiliation and bullying. The scene in which Banks screams “we were rooting for you, we were all rooting for you” at a contestant who she deems to have “given up”, while the contestant mutely receives the barrage, has become a meme. In the documentary, Banks concedes that she may have gone too far in that moment; but as an entertainment industry professional, she surely knows that she went exactly far enough for her audience.

There’s a maddening refusal to take responsibility from the show’s creative team, who all claim to have no control over the show they were making. With impressive chutzpah, Banks says in the documentary that she was not involved in the construction of Sullivan’s “cheating” narrative, even though a clip from ANTM shows Banks baiting a tearful Sullivan into a conversation about infidelity after the incident. But there’s also undeniable truth when Banks points out that the deranged challenges came about because “you guys” (meaning the audience) “were demanding this”.

ANTM was an instrument for humiliation as entertainment, and the only people who appear to have believed ANTM was about launching modelling careers seem to be the girls who competed in it. They were duped. Perhaps you could argue, as some of the show’s former creatives do in Reality Check, that the brutal conditions, the relentless objectification and even the the sexual harassment were fair preparation for industry as it then was, but very few contestants went on to have modelling careers, never mind to be “top models”.

Those who did pursue fashion careers say the show was more of a hindrance than a help, and several changed their names to shake the association. (Winnie Harlow, perhaps the biggest star to come out of the series, competed under her birth name, Chantelle Young). Reality stars were perceived as tacky and shabby when the show first came out: Kim Kardashian is a couture muse these days, but it took until 2014 for her to be deemed worthy of a Vogue cover. By then, ANTM had lurched even further into the gimmicky and extreme.

Banks was successful as a model, but she was a genius at reality TV. “I do feel like I can feel and taste what people want to see,” she tells her interviewer in the documentary, and — however monstrous she appears at junctures — she is correct. Her participation in Reality Check suggests that, right now, she can feel and taste that people want to see contrition. In recent years, revisiting the iniquities of reality TV past has become a genre in its own right, with documentaries dedicated to trans bait-and-switch dating show There’s Something About Miriam, weight loss contest The Biggest Loser and the treatment of Big Brother’s Jade Goody, among many others.

But the big lie of the “reckoning” industrial complex is that audiences have moved beyond the manipulation and cruelty that marked the media of the Noughties. When I finished watching Reality Check, the Netflix algorithm auto-recommended that I start Love is Blind. In 2024, Love is Blind was the subject of a New Yorker report by Emily Nussbaum that asked: “Is Love is Blind a Toxic Workplace?” Participants alleged that they had been emotionally exploited, exposed to dangerous situations and unfairly edited (changes the production team denied). Maybe, two decades from now, Love is Blind will get its own appalled documentary, and the makers will repackage themselves as contrite victims of a distant era’s morals.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe