The Age of Disruptors. Image: JG Fox, Getty

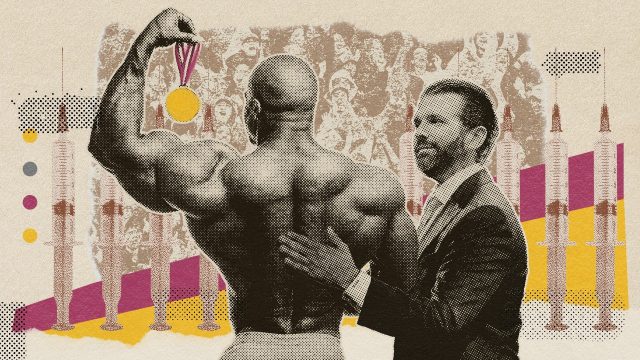

In 100 days, a man will be making the final preparations for his attempt to run faster than any human being in history. Fred Kerley, the 2022 world 100-metre champion, has publicly set a target of 9.42 seconds — a time that would obliterate Usain Bolt’s world record of 9.58 by nearly two-tenths of a second. He will do it while openly using performance-enhancing drugs. His backers include Peter Thiel, the Winklevoss twins, and Donald Trump Jr, who all believe this race could help destroy the Olympic Movement and revolutionise healthcare, all while making them billions of dollars.

When the Enhanced Games were first announced in 2023, the reaction was derision. Travis Tygart, CEO of the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) called them a “dangerous clown show that puts profit over principle”. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) condemned the concept as “dangerous and irresponsible”. Lord Sebastian Coe, head of World Athletics, offered the bluntest verdict: “Well, it’s bollocks, isn’t it?”

The early coverage reinforced the freak-show narrative. Australian swimmer James Magnussen, the 2011 and 2013 100-metre freestyle world champion, promised to “juice to the gills” and break the 50-metre freestyle world record. He gained 50 pounds of muscle and became so large that it took four people 30 minutes to squeeze him into his racing suit.

Two years later, it doesn’t look like bollocks. Athletes are signing contracts and cashing cheques — the most money many have ever earned, given the modest pay available to amateur competitors.

At an Enhanced Games-sponsored event in February 2025, Magnussen lost a $1 million prize to a leaner Greek swimmer, Kristian Gkolomeev, who had been on performance-enhancing drugs for only eight weeks and swam 20.89 seconds: 0.02 seconds faster than the existing world record. Gkolomeev’s wife had written that he earned “as little as $5,000 a year” as one of the world’s top swimmers competing by the rules. In those 20.89 seconds, Gkolomeev changed his life.

The Enhanced Games debut on 24 May 2026. What began as a laughing stock is becoming something harder to dismiss. The organisation now has around 50 to 60 athletes on its payroll across swimming, track and field, and weightlifting — including Hafþór Björnsson, the Icelandic strongman who played The Mountain in Game of Thrones, who will attempt to exceed his own 510kg deadlift record while competing against longtime rival Mitchell Hooper — with 40 participating in supervised clinical trials. Athletes who choose to enhance will travel to the UAE for four months of supervised training starting in late January, with protocols managed by a global clinical trials organisation for health, safety, and performance reasons. The permitted substances include testosterone replacement therapy, approved steroids, oestrogen, peptides, and sleep aids. Cocaine and heroin remain prohibited.

It helps that there’s serious money behind the venture. Don Jr announced his backing in February 2025, declaring that the Enhanced Games represent “the future — real competition, real freedom, and real records being smashed”. He linked the venture explicitly to the administration’s broader agenda: “This is about excellence, innovation and American dominance on the world stage — something the MAGA movement is all about.”

The Trump family’s involvement raises uncomfortable questions. Michael Duff, a labour law professor at Saint Louis University and former trial attorney with the National Labor Relations Board, told me the arrangement “meshes all-too-well with transhumanism, which is what these games seem to represent”. He drew a comparison to other instances of presidential relatives shrewdly monetising proximity to power: “To me there is not a whit of difference between the Hunter-Joe Biden and the two-Donalds pairings. It is a form of dynastic aristocracy that goes back a long, long way.”

The timing is notable. The US government has been withholding $3.6 million from WADA over a Chinese doping scandal involving dozens of swimmers. Enhanced Games founder Aron D’Souza has publicly welcomed what he calls an “age of disruptors” in the White House, and has framed the event as a populist challenge to corrupt international bureaucracies. “The IOC president flies around the world in a private jet. He lives in a palace,” D’Souza has said. “The IOC system is designed to benefit bureaucrats, not the athletes.” WADA’s Witold Bańka has called on American authorities to prevent the event from happening. The Trump administration — sceptical of international bodies and with the President’s son heavily involved financially — almost certainly will not comply. A Truth Social post from the President endorsing the Enhanced Games would be worth more than any advertising budget.

There is an irony here: even as Trump celebrates the United States hosting the 2026 World Cup and the 2028 Olympics and the 2034 Winter Olympics, his son is investing in a venture that seeks to undermine conventional sport’s entire legitimacy.

The organisers have studied another recent transformation of vice into mainstream entertainment. Christopher Jones, the Enhanced Games’ Chief Communications Officer, previously worked at FanDuel, the sports betting platform now valued at approximately $31 billion. Some of the same people who helped legitimise one previously stigmatised industry are now trying to create another. “Look at the investors involved,” Jones told me. “They do not get involved with losers.”

And those investors want to make money. Jones described the Games as “the kickoff to a consumer products division”. The organisation is already selling testosterone therapies, peptides, and enhancement protocols on its website, using social media clips and athlete testimonials as proof points. Clinical data generated by athletes could support an FDA approval process for additional performance and recovery products aimed at the general public. The billionaire businessman Mark Cuban once funded his own study into the effect of human growth hormone on injured athletes, telling me there was simply no other way to gather such data legally. The Enhanced Games hope to generate far more.

The organisation has announced plans to go public in 2026 at an enterprise value of $1.2 billion — a valuation tied up primarily in their pharmaceutical business. To understand what’s at stake, consider the comparison: the global market for GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy is currently worth around $70 billion and is projected to exceed $200 billion by 2033. The Enhanced Games are betting that testosterone, peptides, and performance-enhancement protocols could capture a meaningful slice of that demand — pharmaceutical self-improvement marketed with the same slick simplicity as a Hims & Hers subscription.

Shane Ryan, a 31-year-old, three-time Irish Olympian and world medallist in swimming, described the arrangement as something closer to a tech startup than a sporting body. “It’s a business,” he said. “Once you learn how much money is actually invested in it, you realise it’s not going to go away.”

Ryan joined the Enhanced Games after retiring from traditional competition. “I made like $20,000 or €18,000 a year,” he said of his time competing for Ireland. “You can’t live on that.” The Enhanced Games offered him a salary, comprehensive recovery support, and the chance to see how far his body could go.

Whether any of this truly succeeds may depend on Kerley’s race.

Given that the 100-metre record is the one thing even the most casual of fans will understand, the Games will remain a curiosity until enhanced athletes run faster than clean ones. A USADA official who spoke on condition of anonymity put it plainly: “If somebody breaks that record, everything changes.”

The official identified a specific scenario the organisation might be hoping for: a white sprinter breaking the record in a discipline dominated by athletes of West African descent since Jim Hines first broke 10 seconds in 1968. “If the first iconic Enhanced sprint record comes from a white guy, the marketing machine goes into overdrive,” he said. Only two white athletes have ever run under 10 seconds — France’s Christophe Lemaitre (9.92 in 2011) and Virginia Tech’s Cole Beck (a wind-aided 9.87 in 2023) — and neither is currently signed with the Enhanced Games. But the USADA official argued the commercial potential would be, in Trump’s colourful turn of phrase, “yuge”.

Anthony Roberts, author of Anabolic Steroids: Ultimate Research Guide and a fitness journalist who has broken major steroid stories for The New York Times, offered a realistic view. “The Enhanced Games stick around as long as rich people fund it,” he told me — and in my conversations with the Enhanced Games team, it is clear they have a great deal of financial runway, carrying them through multiple iterations of the signature event. “Because it has mostly attracted retired athletes off the podium, I can’t see it becoming popular at the mainstream level. The top sprinter in the Enhanced Games isn’t currently faster than the top sprinter at the Olympics.”

The USADA official was similarly doubtful about the Games supplanting traditional competition. “The Olympics are baked into national identity, government funding pipelines, and a century of habit,” he said. But he acknowledged the organisers had put serious money in. His primary concern was the message the event sends to young athletes, most of whom are already experiencing money pressures in their chosen sports. “We already fight a constant battle to keep kids from thinking they need drugs to chase a scholarship or a pro contract.”

The organisers are not, as they explain it, trying to destroy the Olympics. They are trying to piggyback off conventional sport’s legitimacy while building a pharmaceutical empire on the side. Even so, the Games arrive at a time when moralistic conventions are under threat. Sports betting, once viewed as dangerous and confined to the shadows, is now embedded in all major broadcasts. GLP-1 drugs have made pharmaceutical weight loss mainstream, rapidly supplanting the more respectable custom of dieting. The Enhanced Games are betting that performance enhancement will follow the same trajectory, going from taboo to tolerated to normal: a future in which ordinary consumers pay for testosterone, peptides, and recovery protocols to get stronger, leaner, and younger-feeling. The long-term health consequences of mass-market hormone use remain largely unstudied, but the Enhanced Games are wagering that demand will outrun caution — as it did with sports betting, and as it is doing with GLP-1s.

Importantly, they are also a post-national venture in a time of declining trust in and identification with nation-states. Athletes will not represent their countries; there will be no anthems, no medal counts by nation. Whether audiences will care as much about competitors without flags remains an open question, but the organisers are wagering that records and spectacle will prove sufficient.

For athletes like Shania Collins, a 29-year-old retired American sprinter and former US Indoor Champion, the appeal is transparency. She competed for six years as a professional, earning what she described as the bare minimum. “I had confidential sources and I’ve seen things that led me to believe that [competitors] were taking performance-enhancing drugs,” she said. “It always felt like an unfair playing field.” Her mother has taken to calling it “the honest games”.

Come May, amid the manufactured glitz and 24/7 gambling of Las Vegas, enhanced athletes will get to chase — and possibly exceed — times that clean competitors have never approached. If Fred Kerley breaks Bolt’s record on a global broadcast, investors such as Don Jr will have seen an early return and the Enhanced Games will have proved their thesis: that the appetite for superhuman performance outweighs any squeamishness about how it was achieved.

If no one does, they will at least temporarily remain what their critics have called them — a well-funded sideshow still awaiting its big moment.

Either way, the answer will come down to a fraction of a second.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe