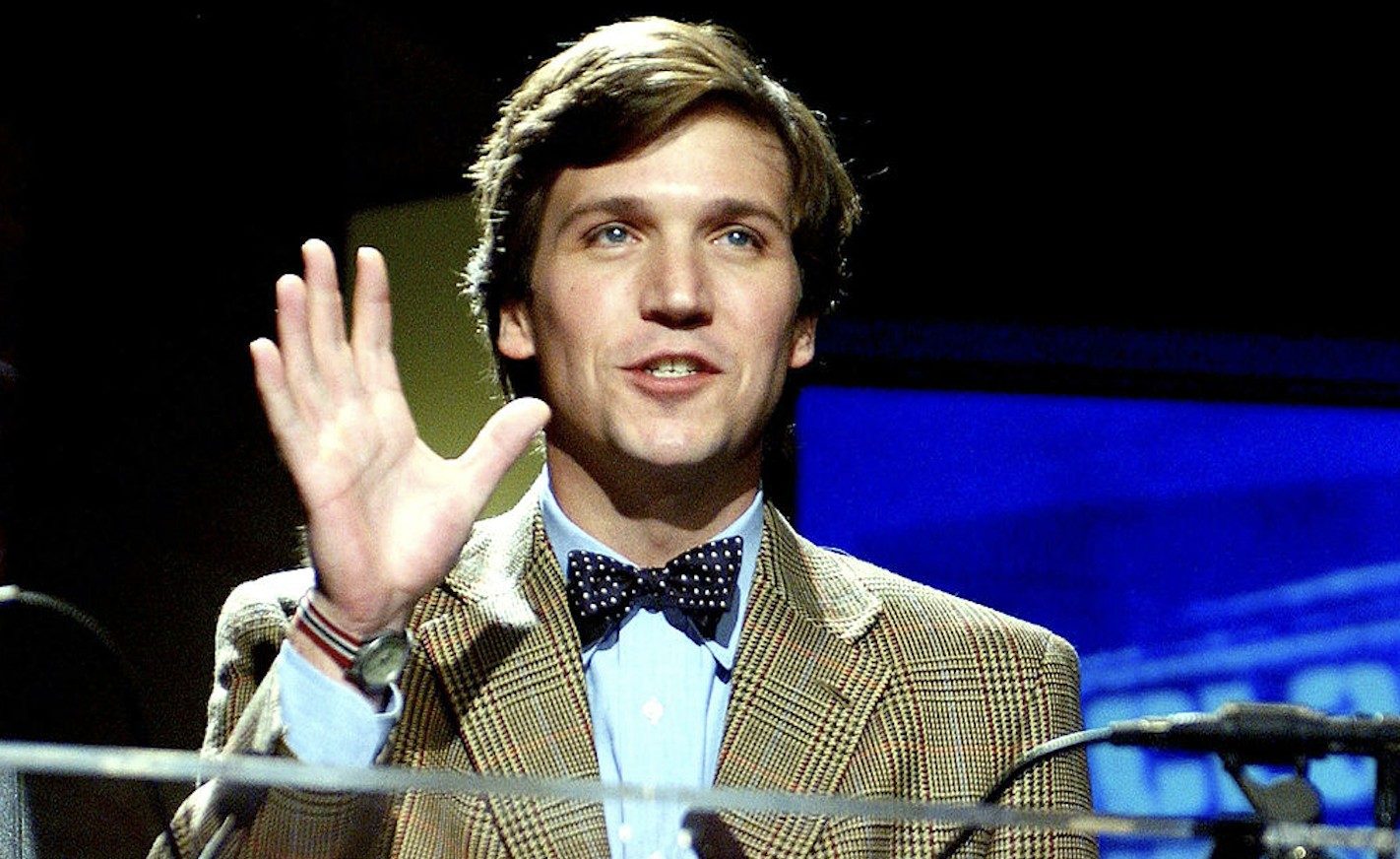

What happened to Tucker? (Chip Somodevilla/Getty)

The word “actual” entered the English language in the early 14th century before the suffix “-ly” was added a hundred or so years later. Back then, “actually” meant “real and existing” as opposed to “in possibility”. But recently it has taken on a second meaning: to highlight unexpectedness or to contrast with expectation.

There is no greater purveyor of “actually” and its new meaning than Tucker Carlson. Tune into any one of his podcasts, interviews or speeches and the adverb’s all-encompassing power is on full display. “Damn you, actually”; “He is evil, actually”; “Who is actually for open borders?”; “If there’s one lesson in American politics, it’s that people in charge lie, actually, they do!”

People in charge do lie, actually. And for many years, Carlson made a career of holding these people to account. His incisive psycho-portrait of George W. Bush as a cavalier, even callous, governor raised early alarm bells about his presidency. His puckish profile of James Carville exposed the lavish lifestyle of a man who claimed to speak for America’s downtrodden. And even in his Fox News days, his grilling of Senator Lindsey Graham over US bomb strikes in Syria gave voice to Republicans and Democrats who were sceptical about further military intervention in the Middle East.

But since leaving Fox in 2023 and starting one of the world’s most popular podcasts, such interviews have grown few and far between. In their place has emerged a far more questionable roster of guests: from Vladimir Putin to a Nazi-curious Groyper, to a former crack addict claiming to have slept with Barack Obama. To Carlson’s supporters, these guests merely signal a willingness to go where others will not. For others, including his former friends and colleagues, it prompts a basic question: what the hell happened to Tucker?

A new book by New Yorker writer Jason Zengerle attempts to answer this question. The aptly named Hated by all the Right People is neither a hit piece nor a hagiography; it is a chronology of Carlson’s ascent and descent, drawing on interviews with those who knew or worked with him. It traces the transformation of a talented young writer into what Zengerle describes as a “noxious talking head”.

Once a fledgling journalist at The Weekly Standard, Carlson soon became CNN’s youngest-ever anchor, later hosting shows at MSNBC, co-founding the Right-leaning news site Daily Caller and rising to become the most-watched host in Fox News history. He has lived many lives and yet in each one, traces of the new Tucker can be found in the old: ideological flexibility, a penchant for provocative ideas, and, above all, a desire to entertain.

As a young writer, Carlson’s stories were eclectic: a weekend with spud gun aficionados, reflections on British colonial architecture, and a trip to war-ravaged Liberia with Cornel West and Al Sharpton. They were nearly all humorous and perceptive, so much so that even Christopher Hitchens was a fan. But compared with today’s darker, more conspiratorial output, they seem almost unrecognisable. In the past month, his podcast has published episodes such as “the demonic rituals to replicate God”, “Diddy, demons and the antichrist”, and “Why are you gay?” (also featuring demons).

How can we make sense of the spud-to-demon pivot? As the book intimates, part of the answer lies in Carlson’s transition from print journalism to broadcast in the early 2000s. In print, ambiguity was an asset: euphemism, colour, and nuance were the alchemy of magazine writing. Broadcast punditry rewarded the opposite. “One benefit of hosting a talk show is that it forces you to take a position on virtually everything that happens in the news,” Carlson once said. “That’s also the downside… From ‘complicated’, it’s a short trip to ‘nuanced’. Nuance, needless to say, is the enemy of clear debate.”

He discovered this truth the hard way. Installed as the conservative foil on CNN’s political debate programme Crossfire, he was paired with a liberal cohost, the two trading rehearsed blows on the controversies of the day. Then Jon Stewart came. Appearing as a guest in 2004, the Daily Show host humiliated Carlson and his cohost, claiming they were “hurting America”. Turning directly to Carlson, Stewart mocked his bow tie, called him a “dick”, and dismissed the show as performance politics masquerading as journalism. The encounter quickly went viral (by 2004 standards) and Crossfire was cancelled soon after.

Although Carlson went on to host another show, this time at MSNBC, the Crossfire episode left its mark. The bow tie (eventually) disappeared and so did his television career, at least for a few years. What stung most, though, was not Stewart’s mockery, but the realisation that he was right: Crossfire was combative by design, and it forced Carlson to defend conservative positions he didn’t necessarily agree with.

As Zengerle writes, Carlson’s conservative politics were a direct reaction to the “weird, wild, and woolly hyperliberalism of 1970s California” that he grew up in. But his conservatism was more instinctive than ideological or academic (he flunked most of his classes anyway). There were no Buckley-esque disquisitions on the collectivist nature of higher education or Charlie Kirk-style debating tours. Instead, he preferred to play the troll: when liberal students at Trinity College protested a CIA recruiting event, Carlson scrawled “WELCOME CIA” onto a bedsheet and hung it from his dorm-room window. When he was invited by the protesters to make the case for the CIA, he took to the stage and said: “I think you’re all a bunch of greasy chicken fuckers,” before walking off.

As Carlson confessed in 2011, he was never particularly ideological: “my politics are so complicated I don’t even understand my own politics a lot of the time” — a disposition that helps to explain why he ricocheted across nearly every corner of conservative thought over the past 25 years. When he joined the Weekly Standard in the late Nineties, he was a self-described “Episcopalian neocon”. Then, after the 2001 Iraq invasion, which Carlson initially supported, he moved in a libertarian direction (ably supplementing his income as a fellow at the Cato Institute). Now, he is the country’s foremost national-populist, criticising America’s cultural decay, forever wars, and mass migration on his podcast.

In some ways, his evolution on these issues reflects the Right’s own realignment from Bush-era conservatism to Trumpian populism. In the early 2000s, the bow-tied Carlson was a cipher for the median Republican voter: an Iraq war-supporting WASP who largely believed in free trade, tax cuts and deregulation. But as the Right moved in a more populist direction under Trump, so did Carlson. In the online parlance, he became “red-pilled”. “He is now like a mini version of Steve Bannon,” a longtime acquaintance of Carlson’s told me. “He’s an ultra non-interventionist. He doesn’t want us involved in any foreign wars, including Venezuela and Greenland.”

According to Ross Douthat, Carlson developed a “deep distrust of all institutions” that was “a transformation of mentality as much as substance” — like many on the Right. Events such as Russiagate, Covid, and the border crisis cultivated a feeling in Carlson that the ruling class was not merely negligent or incompetent, but actively “evil”. This explains why, in a recent episode of his podcast with Matt Gaetz, he asserted with absolute conviction that soldiers were being deployed to the Middle East only to die for the US government and provoke a war on its behalf.

While Douthat’s theory of Carlson’s ideological evolution may be true, it overlooks baser considerations. Following the Crossfire humiliation, Carlson took a simpler lesson from his clash with Stewart: arguments matter less than popularity. In Carlson’s mind, Stewart only “won” their debate because he was more popular. “I didn’t lose that debate,” he later said. “I thought his argument was stupid, but the more popular guy wins… He won because he’s more popular than I am.”

But for Tucker to win, he had to be popular first. After a failed stint on Dancing with the Stars in 2006 (he was knocked out in the first round) and the founding of the Daily Caller, Carlson joined Fox News in 2009. Beginning as a substitute host for Bret Baier and Sean Hannity, he ended the 2010s as the network’s most popular news host in cable TV history. “Tucker covered some really weird shit at Fox,” one former colleague told me. “But his audience loved it, which meant Fox loved it.”

This “weird shit” included a documentary on testicle-tanning, a segment on the sex life of pandas, and a special on cattle mutilations. It also featured attacks on his own party alongside praise for liberals such as Democrat Senator Elizabeth Warren. “Tucker was his own island at Fox,” a former Fox employee told me. “He had his own team and they were very tight-lipped about what they were going to talk about on the show,” she said. “No one else at Fox would have any idea.” That culture of secrecy extended to fellow Fox hosts too, which occasionally resulted in clashes on air. When Carlson criticised then-Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos for adding $13 billion to his fortune during Covid, Sean Hannity responded: “People can make money. They provide goods and services people want, need and desire. That’s America.”

These attacks helped to crystallise Carlson’s new persona: the preppy populist in a gingham shirt and repp tie, happily scolding elites on both sides of the aisle. But beneath the political posturing, he knew that his primary role was to entertain. Whether ululating in a high-pitched voice or staring at guests with bovine incomprehension, Carlson perfected what Charles Pierce called authentic artificiality, crafting a sarcastic, excitable persona.

Behind the easygoing façade, however, Carlson was monomaniacally focused on ratings. Unlike other cable news networks, Fox tracked viewership minute by minute, allowing hosts to see precisely how each guest or segment performed — a system he monitored closely. If a segment performed poorly or a guest overstayed their welcome, he would bristle with anger. In 2017, after learning that a guest had run long, Carlson screamed “Fuck!” in front of a visiting New Yorker writer. “Ratings at Fox are everything,” said the insider. “He would have felt that.”

That obsession didn’t end when he left Fox. If anything, it has grown stronger. Running his own podcast, unconstrained by network guardrails, and knowing what feeds the beast, Carlson burrows ever deeper into rabbit holes about who did 9/11, whether Brigitte Macron is a man, and the rise of globalist death cults — all the while raking in millions of views and lucrative sponsorships, from MyPillow to telemedicine services for pets. At the same time, he became a staunch critic of Israel (and a big fan of Qatar), flitting between legitimate criticisms of the Jewish state to more unsettling rhetoric. As well as welcoming a Holocaust denier on the show, Carlson references men “eating hummus”, Putin “kicking money changers out of the temple”, and professes a greater hatred for Christian Zionists than Nazis and jihadists.

None of these remarks individually meet the threshold of antisemitism, but each one nudges closer to the precipice. Just this week, for example, Carlson claimed that there has never been a real antisemitic movement in America — a plainly ahistorical statement that ignores events like Charlottesville in 2017, when demonstrators chanted “Jews will not replace us!” as well as the existence of groups like the National Alliance, Aryan Nations, and the KKK in the 20th century.

To his fans, Carlson is “just asking questions”, but this framing masks the cumulative effect of his commentary. By repeatedly raising topics related to Israel and, by extension, the Jews, his questions take on a rhetorical weight that goes beyond curiosity. Indeed, this was precisely what he criticised Pat Buchanan, the paleoconservative founder of the American Conservative magazine, for. “It’s this kind of relentless bringing up of topics related to Judaism,” Carlson noted in 1999: “I do believe that there is a pattern with Pat Buchanan of needling the Jews. Is that antisemitic? Yeah!”

Unlike Buchanan, Carlson has — at least publicly — not expressed an interest in running for office. If he did, there is every chance that he would perform well. All the raw materials are there: high name recognition, a huge platform, and a keen understanding of how Washington works. “If he wanted to, Tucker could easily scoop the GOP nomination in ’28,” said one acquaintance. “The base loves him.” What kind of candidate might emerge then? A MAGA-style isolationist or something new? For the first time in his life, he would be responsible for answering the very questions he has spent his career asking. That might be the most dangerous proposition yet, actually.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe