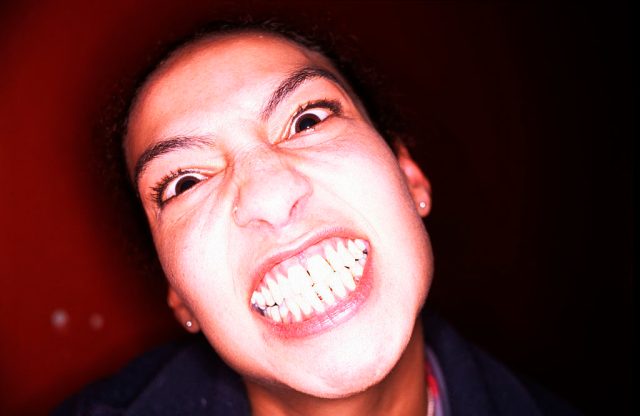

This is not a generation at ease with itself. Photo by PYMCA/Avalon/Getty Images.

Here and there you can still see evidence of the collective madness of the Covid era. Some “social distancing” markers still linger on pavements or shop floors. Occasionally I find a face mask in a coat or handbag I haven’t used for a while. There was a feeble official “day of reflection” recently. But for at least some of us, life is sort of back to the way it was: four in ten workplaces are back in the office full-time, dog walkers are no longer hunted by drones, and the shops and churches are open. We mostly don’t talk about the Scotch egg thing, or being forced to say goodbye to dying loved ones by videolink.

But the kids are not alright. Back in 2020, we had no idea what the impact of lockdown would be on those young people whose normal development was so casually interrupted. And while every parent has a lockdown horror story, it was the most vulnerable children who were worst afflicted. Lockdown widened the school attainment gap, delayed children’s development, and plunged a generation of tweens and teens into psychiatric turmoil. But it didn’t just harm children; it also formed them. Especially for those who came of age concurrently with lockdown, the sheer strangeness of that period was itself a worldview-shaping experience — in ways we’ve scarcely begun to grasp.

Some of this was an effect of lockdowns forcing ordinary life online. This sense of reality coming unstuck preceded Covid, but was sharply intensified by it. I recall being taken aback when, toward the end of the Covid era, I had a conversation with a woman in her early twenties who cheerfully argued that not only is the earth flat, but also birds aren’t real. She might have been joking; but it felt like she wasn’t. Then again, if you’d just spent two formative years with nothing to do but scroll, you might be forgiven for concluding that there’s no meaningful difference between reality and internet memes. After all, in that situation most of your reality is internet memes.

This sense of generalized unreality seems to have become, especially for the young, a permanent fixture. Just recently, Channel 4 warned that Gen Z has lost trust in authoritative sources of information, preferring online sources of information, gathered in a “magpie” fashion and validated by peers. This echoes a broader trend noted last month by liberal commentator Anne Applebaum, who deplored the rise, across the globe, of a politics fusing New Age beliefs with anti-democratic practices. In this worldview, she laments, “superstition defeats reason and logic, transparency vanishes, and the nefarious actions of political leaders are obscured behind a cloud of nonsense and distraction”. She contrasts this critically with her own worldview, in which — she says — “logic and reason lead to good government”, and “the political order inheres in rules and laws and processes”.

But from the perspective of the “Birds Aren’t Real” cohort, we might ask: where was Applebaum’s logic and reason, during the multi-year collective freakout in which buying a Scotch egg prevented Covid infection, and children cut mouth holes in N95 masks to play the flute? For the unreality wasn’t just online; it was everywhere, often accompanied by vigorous social shaming and coercive state power. Asking zoomers of my acquaintance for their memories of Covid, the most common theme was the absurdist tyranny of Covid rules — and then how politically formative it was to defy them. One young friend describes seeing a group of “Covid marshals” exit the van in which they’d traveled together unmasked — and then, after climbing out, donning masks and fanning out through London streets to enforce mask-wearing and social distancing among pedestrians. Another remembers quietly abandoning mask mandates, and realizing that doing so had no effect.

I don’t want to get bogged down in who went crazier. My point is simple: a whole microgeneration experienced, on the cusp of adulthood, a collective and officially enforced reality in which every rule suddenly turned nonsensical and authoritarian, at their expense and in the name of a threat that didn’t really affect them. How do you respond to an experience of this kind? At the extremes, the answer seems to divide between those who concluded that when the world is so arbitrary, there’s no point trying to do anything; and, conversely, those who concluded from this there are no limits at all on what could be done.

At one end of the spectrum, Gen Z has checked out. The youth mental health crisis preceded Covid, but lockdown escalated it. In its wake, disability claims have risen most sharply among teenagers and young people. Among claimants under 25, 70% were for mental or behavioral conditions, accounting for more than half of the rise. Labour’s Wes Streeting recently asserted that such conditions are “overdiagnosed”, and this may be the case. But it may also be the case both that the distress is real, and also that these young adults are just doing what they were conditioned to do. Given that they spent two years forcibly shut in with only the internet for company, while the government paid for everything, it would not be surprising if some of those young people might be a bit screwed up. Nor would it be surprising if many of them simply view this situation as normal, and expect it to continue.

Some of those young adults are now spiraling in psychological distress, and perhaps also learned helplessness. Lest anyone mistake me, I absolutely don’t want to shame those people. The shame should be on everyone who assented to policies that deprived a generation of normal coming-of-age experiences, in the name of a virus that posed little risk to them. What we owe to these now perhaps deeply damaged young men and women is not disability benefits, but contrition, reparations, and a way out of the hole we shoved them in.

But at the other end of the spectrum are those young people who drew the opposite conclusion, and are as a result exiting the political mainstream altogether. Again, small wonder: their entry into adulthood was equal parts internet unreality, nonsense rules, and finding that the only way to get laid was by flouting the mandates. Scale that up to a whole microgeneration, and the likelihood is that they’re not going to spend their adult lives coloring inside the political lines. For example, we should perhaps not be surprised that Channel 4’s study finds 52% of 13-27-year-olds would welcome “a strongman leader unbound by elections or Parliament”. Like the mental health crisis, the slide toward authoritarian views is a macrotrend that predates Covid; but there’s no question that Covid represented, for many, a definitive rupture. This is, after all, a generation that experienced two years of arbitrary, capricious, and profoundly post-liberal state power. Yes, lockdowns were a form of collectivist authoritarianism; even so, is it really so strange that some would afterwards gaze approvingly at the strongman variety? As one anonymous young commentator put it in 2023, it was “all wisdom of the wise was broken, torn up and transgressed purely to advance the interests of old people”. As a result, the author suggests, those who were young during Covid have concluded that “there is no limit to what politics can achieve”.

Across many European nations including France, Germany, and Spain, the sharpest rise in so-called “far-Right” parties is consistently among the young — and, especially, young men. Just recently The Atlantic described the same phenomenon in the United States, linking it explicitly to Covid. In the UK, when we compare the 2019 and 2024 general election breakdowns, it’s clear that while the Right-wing youth vote hasn’t grown significantly in absolute terms, those young people that do vote Right opted in increased numbers for the party to the Right of the Tories: Reform.

But it’s not just a Rightward tilt; it’s an anti-mainstream one. The same vote breakdown shows the percentage of 18-24-year-olds who opted for the two mainstream parties fell by a quarter, from 77% to 50% of young voters. Along with Reform, the biggest winner among the youngest voters was “Other”.

Coming of age under lockdown, then, seems to have effected a generational exit both from any sense of shared reality, and, by extension, from political normativity. Will this right itself over time? Maybe. But looking around modern Britain, I see few obvious reasons why a twentysomething would feel motivated to salvage a political order that mortgaged future tax revenues to fund years of furlough and misspent PPE procurement, to no measurable benefit over countries that didn’t lock down and to the considerable economic detriment of the young. It is a political order that’s depressing white-collar wages through AI, and blue-collar ones through mass immigration; that’s squeezing young professionals and letting house prices soar, but safeguarding the triple lock.

In his push to get Gen Z to forsake PIP and re-engage, Wes Streeting should perhaps be careful what he wishes for. As this generation reaches political maturity, we should expect British politics to get angrier, more radical, more plural and fractious — and, perhaps, considerably less democratic.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe