Jacques Pavlovsky/Sygma/Getty Images

As well as the most persistent of revolutions, Syria’s was also the most total. Over a decade and more of struggle, the Syrian people ousted not just Bashar al-Assad, but also his army and security services, his prisons and surveillance system, his allied warlords and cynical foreign sponsors. The revolution’s victory saw the end of a dictatorship which had lasted 54 years — and the final death of Baathism, an ideology that ensnared millions of Arabs for almost a century.

Birthed in the heady aftermath of the Second World War, the Arab Socialist Baath Party went through three major stages, each closely related to the vexed political history of the region. The first stage was one of utopian dreams. The second involved military action, powergrabs and coups. The third, and worst, was of ideals betrayed, of personal dictatorships and brutal death squads. Yet, if Baathism has finally entered history, with the Syrian party officially dissolved in February, its story is far from over.

On the contrary, the lessons of Baathism must now urgently be absorbed by a new generation of Arab leaders. From the way it pitted the region’s Arab majority against minorities, and in how it took the ideology’s mythical sense of destiny and placed it into the hands of strongmen, there’s plenty for men like Ahmed al-Sharaa to think about, even if they emerge from very different ideological backgrounds — especially if they hope not to end their premierships either exiled or hanging from a noose.

Founded in Damascus in April 1947, Baathism was the most enthusiastic iteration of Arab nationalism. Whereas Gamal Abdel Nasser understood the Arab world in hard-nosed strategic terms, as a place to exert his own influence, the Baathists had an almost mystical sense of the Arabs as a nation transcending historical forces. As one of its founders put it, this was a people with a “natural right to live in a single state”.

Such high-minded ideas are unsurprising. After all, the ideology was founded by Syrians who had immersed themselves in European philosophy, from Marx to Nietzsche, while studying at the Sorbonne. Two of the three founders were members of minority communities, and it’s useful to think of Baathism as a way of constructing an alternative Arab identity to Islam. While Salah al-Din al-Bitar was a Sunni Muslim, Michel Aflaq was an Orthodox Christian. Zaki al-Arsuzi, for his part, was an Alawite who later embraced atheism.

What all three shared was an eagerness to blend Enlightenment modernism with Romantic nationalism. Arsuzi, for instance, believed Arabic, unlike other languages, to be “intuitive” and “natural”. Aflaq, for his part, turned the usual understanding of history on its head. He considered Islam to be a manifestation of “Arab genius” and deemed the ancient pre-Islamic civilisations of the Fertile Crescent to be Arab too. Never mind the fact that the Assyrians or the Phoenicians had never spoken Arabic.

Like other grand political narratives of the 20th Century, then, Baathism was an attempt to repurpose religious energies for secular ends. Even the word “Baath” means “resurrection”. Consider the party slogan, “umma arabiya wahida zat risala khalida” in Arabic. That means “one Arab nation bearing an eternal message” — which sounds strangely grandiose, even before you realise that “umma” is the word formerly used to describe the global Islamic community, and that “risala” is used for the divine message the Prophet Muhammad delivered to humanity.

If a secular form of messianic faith was one wing of Baathist ideology, you get a sense of the other from the party’s motto. Proclaiming “Unity, Freedom, Socialism”, it evoked a single, unified Arab state stretching from the Atlantic in the west to the Arabian Gulf in the east, and from Syria in the north to Sudan in the south. This Arab state, Baathists argued, must also be free of foreign control, and construct a socialist economic system. That makes sense: the region had long been exploited, both by the Ottomans and their European imperialist successors.

At first, Baathism was spread by rural doctors and itinerant intellectuals. In those early days, the leadership consisted disproportionately of schoolteachers, ruling over a membership of schoolboys. In 1953, however, the party merged with Akram Hawrani’s peasant-based Arab Socialist Party. This brought it a mass membership for the first time, and it came second in Syria’s 1954 election.

By then, though, democracy was becoming ever rarer. Since Colonel Husni al-Zaim’s March 1949 coup, the first in Syria and anywhere in the Arab world, politics was increasingly being determined by men in uniform. The most significant of these soldiers was Nasser, who seized power in Cairo in 1952, and promptly became a pan-Arab hero after successfully confronting Britain, France and Israel over the Suez Canal in 1956.

Nasser’s popularity fuelled an already raging popular desire to eliminate colonial borders and, at the behest of Baathist officers in Damascus, Syria and Egypt merged into the United Arab Republic (UAR) in 1958. Yet Nasser’s conception of unity, one which the Baathists would emulate, was totalitarian. There should be only one leader, one party, one truth. Following Nasser’s orders, the Syrian Baath dissolved itself. It would never be a grassroots movement again.

In the meantime, Syrian officers seconded to Cairo formed a secret Baathist military committee. This marked the start of the Baath’s next stage, with the party now belonging firmly to military elites. Following the collapse of the UAR, in 1962, Baathists tasted power for the first time, seizing control of both Iraq and Syria. The Iraqi Baath had a different sectarian make-up to the Syrian. Its membership was mainly Sunni Arab, which was a minority locally but the majority across the wider Arab world. Iraq’s Shia Muslims, therefore, associated Baathism with Sunni identity and were more likely to join the communists, then Iraq’s largest party. This meant that the Iraqi Baath appealed to some — and may well have been sponsored by the CIA — as an anti-communist force. Its March 1963 coup was accompanied by a massacre of Leftists. In November, however, it was ousted by another coup.

The Syrian Baath retained power from 1963 onwards, but was riven by conflict, culminating in 1966 in an internal coup by Salah Jadid. Arsuzi was brought back from obscurity to play the role of ideological figurehead of the Syrian wing, but most of the party’s original leadership, including Aflaq, fled abroad. Bitar was assassinated in Paris in 1980.

The Baathists turned on each other, its Syrian and Iraqi wings becoming irreconcilable enemies. In Syria, an endless series of purges further sectarianised an already sectarian army. Competent officers were replaced by loyalists, overwhelmingly from the same Alawite community as Jadid and his ally Hafez al-Assad. The consequent weakening of the army may explain the catastrophic loss of the Golan Heights in 1967, when Assad, then defence minister, gave the order to retreat long before Israeli troops actually arrived.

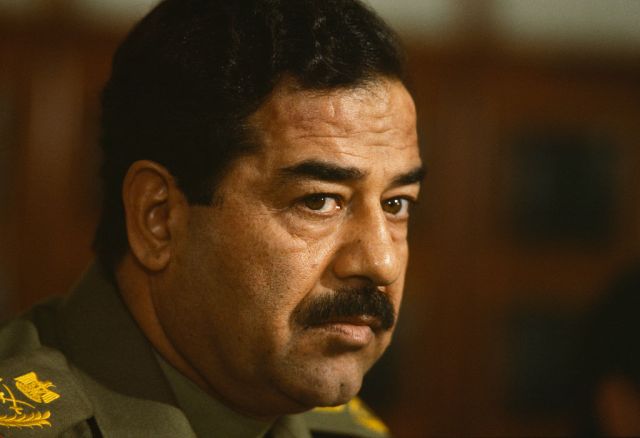

Under Jadid’s “Leninist” leadership, the Syrian Baath practiced a top-down Leftism aimed at eliminating the old bourgeoisie. In 1970, however, the “pragmatist” Assad launched a new internal coup. Jadid was sent to prison, where he languished until his death. Assad eased off the class warfare, concentrating instead on building his own power base. The Iraqi Baath, meanwhile, had returned to power in 1968, and Saddam Hussein ascended within it until he became absolute leader in 1979.

This marks the third stage of the Baath, in which the party became a vehicle for one-man dictatorships. Cults of personality exalted Assad and Hussein with mass rallies and titles like “first pharmacist” or “hero of war and peace”. They were lionised as “eternal leader” and “symbol of the Arab revolution” — as if the hitherto deified nation had been reduced to a single figure.

Some sections of society benefited, for a while at least, from this system. Members of hitherto marginalised rural communities, including religious minorities, entered the army and security services. Some of the urban working class benefited from jobs in the rapidly expanding state sector. In Iraq, enormous oil wealth allowed rapid development of civilian infrastructure. Yet terrifying political repression and massive corruption caused a brain drain, scaring off investment from both Damascus and Baghdad.

Then Hussein’s regime squandered Iraq’s wealth on wars of choice. Despite bloody stalemate against Iran, and embarrassing defeat in Kuwait, Hussein hailed his victories. In this, he borrowed from the Baathist playbook: Assad had done something similar in 1973, after losing to Israel in the Yom Kippur War. The gap between rhetoric and reality was vast and growing, perhaps inevitable given Baathism’s totalising aspirations.

All the while, both Assad and Hussein built fearsome security states. Far from uniting the people, repression in both countries soon took on ethnic and sectarian overtones. Hussein killed tens of thousands of Kurds — the 1988 chemical atrocity at Halabja was especially infamous — before exterminating Shia Muslims when they rose against him in 1991. Hafez al-Assad responded to the challenge of the Muslim Brotherhood by killing up to 40,000 people in Hama in 1982. Then Assad’s son Bashar, who inherited the presidency in 2000, outdid his father, responding to the 2011 revolution by killing hundreds of thousands.

Hussein was deposed by the Anglo-American invasion of Iraq in 2003, and soon met his end at the gallows. Many of his security officers later joined ISIS which — despite its religious rhetoric — is actually the Baath’s closest successor: both revel in mass surveillance, detention and torture.

So what became of “Unity, Freedom, Socialism”? Instead of unity, the Baath brought divide and rule, splintering society by ethnicity, sect, class and region. Instead of freedom from foreign powers, Iraq and Syria ended up occupied. In both countries, socialism ended in sanctions, neoliberalism and graft.

In Greek drama, the tragic hero is brought down by a fatal flaw in their character. The Baath party’s flaw was its identification of the Arabs with state power, and then the reduction of the state to one-man rule. An Arab nation can be said to exist, and sometimes it even transcends state borders. The Arab Spring proved this, when Arabs from Tunis to Sana’a, influencing each other, all revolted simultaneously. But the Arab countries include non-Arab peoples, and the Arabs themselves are plural and diverse, far greater and more creative than a single man or a single mystic ideology could ever be.

That still leaves one more question: what lessons should present and future leaders learn from the failure of Baathism? First, that strong men are brittle and easily broken, whatever their ideology. Second, that the highly centralised, hyper-authoritarian states built by such men end in military defeat and economic collapse. These dictatorships weaken and impoverish society, and provide security to no one, not even to the strong men in the end.

There’s a foreign policy dimension here too. The Arabs have long been assaulted by a string of foreign states: Israel, the US, Russia and Iran. The need to win freedom from the nation’s enemies — or at least to deter their aggression — is more crucial than ever. But seizing control of the state by military force is not sufficient to shift the balance. There are no shortcuts. Lasting power can only be built by liberating the people rather than smothering them: and that means human and civil rights are essential tools in constructing national power. Once the peoples of the Arab and Muslim region are able to express themselves freely and determine their affairs democratically, then their various polities will be ready to coordinate their energies. And that, more than Baathism ever did, will truly change the world.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe