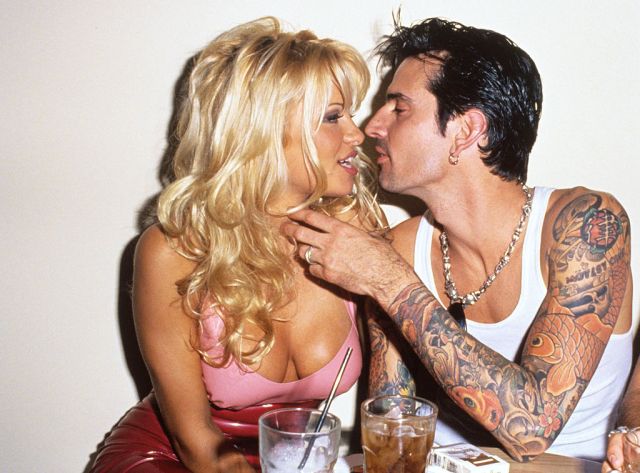

Pamela Anderson, her worst screen couple, and Tommy Lee (Photo by S. Granitz/WireImage)

Pamela Anderson doesn’t live in the same world as you. In your world, the name “Pamela Anderson” (or just “Pamela”, or even “Pammy”) probably brings to mind Playboy, Baywatch, obvious breast implants, bad husbands, sex tape. Bland, brash, commercialised American sex is what Anderson has stood for since the late Eighties. She’s as obviously desirable as a big car or a cold beer. A basic pleasure model.

But Anderson’s personal world is neither crass nor obvious. It’s a hazy, fairytale place, where a small-town Canadian girl could be discovered on the big screen at a ballgame and launched instantly into fame and fortune, despite never having thought of herself as a beauty. The genre of her inner life is romance. “I think of my life not in years, but by who I was in love with at that time,” she writes in her 2023 autobiography (called, romantically, Love, Pamela).

“I call it ‘soft vision’ like how I look to the camera — looking ‘through’ it — even past it — never a direct stare to the lens but a softened focus.” Not base, but beautiful. Pure. Hopeful, even if that hope is more a function of will than a rational response to experience. Her interests are decidedly wholesome: animal rights, veganism (she published a vegan cookbook in 2024). The Anderson we think we know, and the Anderson she knows herself to be, are very different people.

There’s a version of that mismatch in her acting career. Or “acting”, if you want to be unkind, and a lot of people have been. No one took her seriously, apart from herself. In her first film, 1993’s Snapdragon, she plays “a concubine who happens to have a secret twin”. She prepared by studying the Stanislavski Method.

She was nominated for three Golden Raspberries for her starring role in 1996 comic book adaptation Barb Wire: she won “worst newcomer”, but probably more humiliating was being shortlisted for “worst screen couple”, the couple in question being her “impressive enhancements”. It was the Nineties, so nobody thought to call this “body shaming” and in 1999, she had the implants removed.

Now, though, Anderson has finally made a film that people agree is good. More than that, they agree that she is good in it. The Last Showgirl is directed by Gia Coppola, granddaughter of Francis Ford and niece of Sophia. It’s the story of Shelly, the “last showgirl” of the title, played by Anderson: a 57-year-old veteran performer in a glitzy Las Vegas revue called Le Razzle Dazzle, who is forced to confront her own ageing and vulnerability when the show closes down.

Shelly believes that Le Razzle Dazzle belongs to the historic tradition of the chorus line. The world sees it very differently: to Shelly’s adult, estranged daughter, it’s just an embarrassing nudie performance. And when Le Razzle Dazzle closes to be replaced with a “sex circus” (because the world sees Shelly’s show, not as art, but as a dated bit of titillation), and Shelly is forced to audition for other revues, she has to hear what people really think of her.

A dispassionate but not exactly cruel director, played by Jason Schwartzman (another Coppola), lays it out for her: she’s not a good dancer, and even if she ever could have been, it’s too late for her now to acquire the technical skills. She was elevated because she was young and beautiful, and now she isn’t either anymore. In another film, this could be the moment that our heroine turns out an incredible routine and triumphs over ageist, sexist expectations. But The Last Showgirl isn’t that kind of film, and Shelly leaves the stage, defiant but nonetheless rejected.

It’s a sad, brutal scene, made sadder and more brutal by the obvious parallels with Anderson herself — parallels that the actress deliberately draws out. She changed Shelly’s age in the script to match her own, so when she shouts “I’m 57 and I’m still beautiful!” at the Schwartzman character, the words belong equally to the faded showgirl and to the former pinup playing her. And like sweet, dreamy, flawed Shelly, Anderson belongs to a sexual culture that is essentially a relic.

The Playboy centrefolds that made Anderson famous are as much museum pieces now as Shelly’s bejewelled and feathered headpieces — pushed out by the “sex circus” of online pornography and OnlyFans. As for Baywatch, who needs to watch beautiful women running around in red swimming costumes pretending to be lifeguards when you can watch women in nothing at all having unspeakable things done to them on demand?

Like Shelly, Anderson sees the institutions of sexual entertainment that made her as essentially benign: she remembers life at the PlayBoy Mansion as “a beautiful and sensual chaos”, Hugh Hefner himself as “the epitome of chivalry, a true gentleman — elegant, passionate, so charming, and yet with that little-boy giggle”. Recollections vary on this point: Crystal Hefner, a Noughties playmate and Hefner’s third and final wife, remembered the Mansion as leaking and riddled with black mould, Hefner himself as controlling and squalid in her own tell-all book, Only Say Good Things.

This rose-tinted view is not because Anderson has had a fundamentally benign life: she was sexually abused by a female babysitter as a child, and her own father was violent and bullying, once drowning a litter of kittens to punish young Pamela for disobedience. Even gentlemanly Hef ripped her off: Playboy made millions from re-exploiting her image via calendars and videos, none of which was ever shared with her.

And, of course, there was the vast public humiliation of the sex tape, made privately with her then-husband Tommy Lee Jones, stolen from her home and released without her consent. Lawyers acting for the company that commercially released the tape argued that Anderson had forfeited her right to privacy because she’d voluntarily appeared naked in Playboy; Anderson neither sought nor received any money for it.

With all this backstory, a more ruthless Anderson could have easily have reinvented herself with a survivor narrative to suit post-MeToo tastes, much as Crystal Hefner did. (Which is not to say that Crystal Hefner is untrustworthy per se, only that she made her rebrand with cutthroat timing.) But ruthlessness is not an Anderson trait, and many of the decisions she’s made as an adult fit her poorly for the role of victim.

Take the sex tape. As a victim of revenge porn, Anderson is obviously sympathetic — and yet her own romantic choices don’t suggest much solidarity with other women who have suffered like her. Her third husband (and in fact fourth, because she married him twice) was Rick Salomon, the professional poker player and semi-professional sleazeball who distributed a tape of himself having sex with Paris Hilton, against Hilton’s own wishes.

Then there’s the matter of sexual assault. Again, Anderson could leverage compassion here, and deservingly so. But when Julian Assange of Wikileaks was holed up in the Ecuadorian Embassy to avoid allegations of rape in Sweden — allegations described as “credible and reliable” by the Swedish prosecutor — it was to Assange, and not his purported victim, that Anderson gave her support. She became a regular visitor to the embassy; she calls their friendship “invigorating, sexy, and funny”. Assange maintains his innocence and the investigation was dropped in 2019.

Anderson is a “bad victim”, if a victim is supposed to be ideologically coherent and pure. But the truth is that I like her more for these choices, however inexplicable I find them; maybe I like her more because I find them inexplicable. They seem, if nothing else, heartfelt. Still, the same question hangs over Anderson just as it does over Shelly in The Last Showgirl: just how naive is it possible to be?

Like the character she plays, Anderson has thrown herself relentlessly at situations that, in many ways, repeat the exploitation and injury she has already suffered. The audition scene is exquisitely painful because, although the narrative requires us to root for Shelly, the director is unavoidably correct. Shelly’s artistry is, at best, limited. Her sex appeal was her asset, and now that’s almost spent. And all this is true of Anderson too, which spikes the sadness even higher.

What makes Shelly a great role for Anderson is that, finally, this is a part that captures the impossible tension between how the world sees her and how she sees the world. When a romantic character is plunged into a pornographic medium, the result of that mismatch is tragedy, and both Shelly and Anderson have a tinge of tragedy to them. They are women who have been used and discarded, but who still insist heroically on the beauty of things.

Except, for Anderson, there is a second act. She is not pensionless and penniless like Shelly. She can be reborn as an actress who plays a woman a bit like herself. She can even afford to turn her back on some of the labour of femininity that was her profession: in the past few years, Anderson has given up wearing makeup and having tweakments, even for red carpet appearances. The effect is surprisingly powerful, both for revealing the artificiality of regular beauty, and (this part is something of a flex) for revealing how pretty she is unadorned.

At 57, Anderson can receive the respect she was denied when she was young, gorgeous and despised. The real Shellys — the working class of the adult entertainment industry — are more disposable, and their futures more bleak. Maybe there’s something to be said for holding onto a faith in glamour despite all that.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe