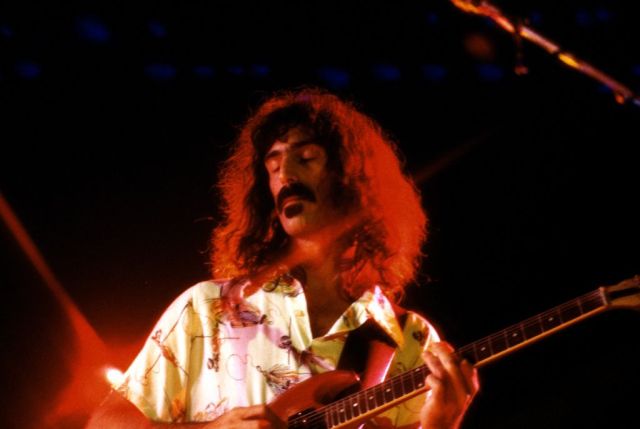

A countercultural icon. Gai Terrell/Redferns

Doubtless the fake nonconformist is an American type that goes back centuries, but we surely reached an apex of fraudulence in the early 2020s. How passionately the rioters of Antifa demanded the same things as Fortune 500 CEOs, how righteously millionaire celebrity “activists” raged for the machine. And there was something mournful too, about Bruce Springsteen and Barack Obama’s coffee table book Renegades, heavy as a tombstone marking the spot where Rock n’ Roll was finally laid to rest. The counterculture had gone full Weekend at Bernie’s.

Of course, it had been green around the gills for a long time. Confronted with the hyper-commercialisation of radicalism in the early Nineties, the political historian Thomas Frank doubted that even its Golden Age amounted to much: “The Sixties was the age of postmodern fantasy and retailers’ dream, for each identity, each new phase of rebellion, necessitated a comprehensive shopping expedition.” The rejection of tradition, Frank argued, was simply the outcome of a desire to be free to flit between images: “They would be rebels, poets, perky-girls, English, hippies, and playboys in quick succession.”

But while there is much truth to Frank’s critique, the counterculture was not entirely bogus. Some hippies really did turn on, tune in and drop out. Hunter S. Thompson may have ended his days writing for Esquire, but all those drugs and guns weren’t going to pay for themselves. The cartoonist Robert Crumb really was a weirdo. And then there was Frank Zappa, guitarist, satirist, avant-garde composer, and writer of “Why Does It Hurt When I Pee?”

It’s difficult, now, to appreciate how famous Zappa was during his lifetime. Yet between the release of his debut LP Freak Out! in 1966 and his death in 1993 at the age of 52, his was a name you knew even if you had never heard his music — and you probably hadn’t, because it was never played on the radio. The one Zappa factoid everybody knew was that his children had strange names, Moon Unit and Dweezil being the strangest. These are tame by the standards of Musk’s X Æ A-Xii, but in 1969 the nurses were so scandalised by “Dweezil” (Zappa’s term for one of his wife’s “funny looking” toes) that they refused to put it on his birth certificate, and he was legally “Ian” until the age of five, when it was changed for good.

I first heard Zappa’s music after taping his concert film Does Humor Belong in Music? which was broadcast deep in the night when I was 16. I was amused by the dirty jokes, but it was also obvious that Zappa’s band had incredible chops. The small Scottish town where I lived turned out to be an outpost of Zappa fandom, and it was easy to get tapes and records. But you never knew what you were getting: Apostrophe was great and Hot Rats was sublime but The Man from Utopia was total crap and Jazz from Hell was unlistenable. Zappa always made sure there was something to annoy or offend everyone.

There was little in Zappa’s small-town Catholic boyhood to suggest he would one day become a counterculture icon. The catalyst for this grandson of Sicilian immigrants was his discovery of “Ionisation”, a dissonant, percussion-heavy piece by the avant-garde composer Edgard Varèse, which Zappa learned about when a hi-fi magazine described it as “the worst music in the world”. Intrigued, Zappa tracked down an LP and was astonished by what he heard. Teenage Zappa corresponded with Varèse and taught himself to compose with books borrowed from the library. He began writing his own orchestral music, funding his passion by drawing greetings cards, scoring films and running a recording studio. After a stint in jail for creating a tape of pornographic sound effects, he realised that if he wanted to hear the music he was composing, he would need a band to play it. He joined an R&B group called The Soul Giants and quickly transformed it into a vehicle for his own ideas, The Mothers of Invention.

The songs that Zappa wrote for The Mothers featured satirical lyrics that were right on the nose and complex music that could switch suddenly from polyrhythms and atonality to doo-wop parody. His timing was perfect: records like Freak Out!, Absolutely Free, and Weasels Ripped My Flesh fit right in with the mid-Sixties “freak scene”. But Zappa took his sound considerably further out than even his most psychedelic peers. In 1969 he released Uncle Meat, a bizarre collage of avant-garde instrumentals, tape manipulation, polyrhythms and spoken word excerpts, and also produced Captain Beefheart’s uncategorisable Trout Mask Replica. Even at their most experimental, The Beatles always made sure that their songs contained plenty of pleasing hooks and melodies, with the result that an ostensibly radical album like Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band still sold by the bucketload; Uncle Meat, not so much.

Zappa held court in his cabin in Laurel Canyon, welcoming the likes of Mick Jagger, David Crosby, Robert Plant, Joni Mitchell, Jimi Hendrix and Grace Slick. Yet he remained an outsider. He didn’t drink or take drugs, and was contemptuous of hippy ideals. He did embrace the sexual revolution insofar as he liked to get laid a lot, both on the road and at home, where he would bring back groupies regardless of the fact that his wife Gail was in the house. However, this was no ideological commitment to “free love”, as Zappa expected Gail to remain faithful. Indeed, the picture that emerges from his daughter Moon Unit’s recent memoir Earth to Moon is of a Sicilian patriarch who worked constantly, saw his children sparingly, and left every aspect of managing the household to his wife, who he also expected to chauffeur him around (Zappa never learned how to drive).

The Eighties were a very different era, of course. By then, almost all the icons of the counterculture had agreed to play by the rules. They were entering their forties, they had homes and cars and wives and ex-wives and children and they knew they had to please the label bosses if they wanted to maintain their lifestyles. Even the notoriously oppositional Lou Reed advertised scooters and dabbled in rapping. Zappa, having gone completely independent in 1979, made no such compromises. He released a triple LP box set called Thing-Fish, featuring songs from an unproduced musical about AIDs and eugenics. He went to Congress to testify against censorship in music (his only allies were Dee Snider of Twisted Sister and John Denver). When he accidentally had a hit with “Valley Girl” (featuring vocals from Moon Unit), he used the windfall to pay the London Symphony Orchestra to perform his uneasy-on-the-ear orchestral music. Unsatisfied with the results, he began writing and performing his compositions on a digital synthesiser called the “Synclavier”, creating bizarre music that was impossible to play with human hands.

Although Zappa affected indifference to how his work was received, Moon Unit recalls that he would “always” complain about “people not taking him seriously, respecting him, playing his music on the radio, or paying him enough money”. He was amazed, then, when he arrived in Czechoslovakia for his first tour in 1990 and was met at Prague airport by a crowd of 2,500 people. For two decades, Zappa was not only given a hero’s welcome but appointed “Special Ambassador to the West on Trade, Culture and Tourism” by Václav Havel (a role that came to an abrupt end when the Secretary of State objected). Zappa started to imagine a different career; he talked about running for president, though not as a Republican nor a Democrat. In his autobiography he described himself as a “practical conservative”, in favour of low taxes and small government. The cancer put paid to that. In his final years he focused on his most complex music, living long enough to see a collection of orchestral pieces performed in Germany, while his dystopian Civilization Phaze III was released posthumously.

Since Zappa’s death three decades ago, many of his peers have also taken the great leap into eternity, while those that remain are preparing to follow. Confronted with death, the old gods of the counterculture from Bob Dylan to Pink Floyd are cashing out, selling off their catalogues to the likes of Sony or UMG or Blackstone. To the naive this may look like a betrayal of principles, but in a world where the top pop star is a middling talent feted by teenage girls, sixty-something male rock music critics and wildly despised political leaders, it’s probably a good idea to get out while the going is good. Besides, “the classics” are what people want: today old songs represent almost 75% of streaming. And none of those cultural revolutionaries ever objected to getting rich, anyway.

As for Zappa, an unequal division of the estate by his widow following her death in 2015 led to lawsuits and public feuding between the siblings, so it was perhaps a relief when the catalogue was finally sold off to UMG for an estimated $25-30 million in 2022. Dozens of albums have been released since his death, while Dweezil regularly tours, faithfully performing his father’s music, although the last time I saw him play I was one of the youngest people in the audience (and I was 45 at the time).

Sometimes I wonder if Zappa might one day be rediscovered as a serious composer if his Rock music were to be forgotten. Now that I know the works of Varèse, Stravinsky, Messiaen, Alban Berg, and Conlon Nancarrow myself I can see what he was getting at with all the difficult stuff I didn’t like as a teenager. But as much as the world would not be losing one of its artistic treasures if a song like “Broken Hearts Are for Assholes” were to vanish from memory, it would make Zappa a less interesting figure. He was what his peers only pretended to be; a true nonconformist, who pursued the path of most resistance not because he wanted to, but because he had to.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe