The Conservatives won the long war of the Seventies (Photo by Cynthia Johnson/Getty Images)

There’s a very good chance that you remember nothing at all of the Democratic 2020 primary cycle, maybe Bernie Sanders’ uncombable hair, maybe Elizabeth Warren mouthing some policy proposal that sounded smart even if no one understood it, maybe the odd moment when everybody abruptly dropped out of the race leaving Joe Biden as the winner. But if there is a moment that sticks, it would likely be when Kamala Harris took Biden to task for, of all the things in the world, busing.

“You worked with [segregationist Senators] to oppose busing,” Harris said in a 2019 debate. “And, you know, there was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day. And that little girl was me.”

It was an effective assault, abetted by the element of surprise. Above all because busing had disappeared from the national conversation 50 years ago. Biden, in the one off-the-record moment of his that makes me actually like him, turned to his debate neighbour Pete Buttigieg as soon as the cameras were off and said: “Well, that was some fucking bullshit.”

But Harris’ salvo was indicative of a general schism within the Democratic Party — and it’s telling that, according to a Politico article on the incident, she was willing to sacrifice a future career with a Biden administration in order to make this point. The Seventies revealed fundamentally different strains within the Democratic Party. The past half century may be thought of as a time loop of the Dems rehashing the same debates — not least because so many senior figures in the party were also around at that time. Perhaps Harris’ catastrophic loss in the 2024 election can be thought of as the end of that cycle.

In the Seventies, the Democrats protected a fraying vision of the Great Society. Courts appeared to cement liberal principles into law, but public confidence in what was essentially a social democratic state was dissipating. The Republicans, in their period of exile at the time, withdrew from that system altogether with the famous formulation “government is the problem”. But the Democrats found themselves pulled in different directions — and continue to be all these years later.

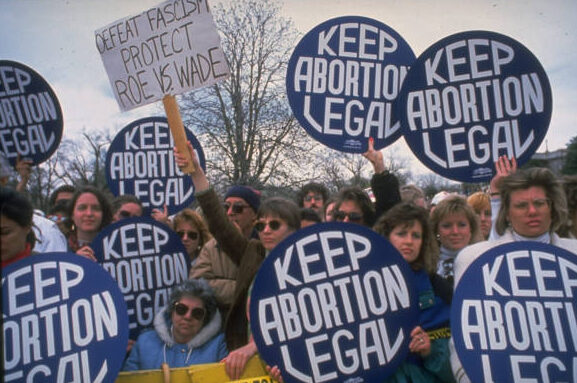

Back then, the progressive wing of the party felt that it was on the cusp of a kind of cultural Götterdämmerung — finally putting to bed the monsters of America’s past and ushering in a more socially equitable society. That narrow success was symbolised by the vanishingly slight margins of victory in Roe v. Wade (1973), which used a somewhat tangential legal argument to close off the abortion debate, and in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), in which affirmative action survived through the highly ambivalent opinion of a single Supreme Court justice. But the Reagan Revolution and the gradual Rightward turn of the courts meant that progressives have had to fight tooth-and-nail since then for the kinds of social gains that for a brief moment in the Seventies seemed like they might materialise through popular will. Those causes included the long battle for gay and lesbian rights, which finally culminated in the Supreme Court’s 2015 support of gay marriage; the battle against restrictions on pornography and sexual harassment; and the battle for the Equal Rights Amendment, which had at one time seemed a foregone conclusion and then was fought out in a guerrilla campaign before finally being abandoned sometime in the Eighties.

To the extent that the short-lived Kamala Harris movement had a coherent theme, it was about going back to this moment in time in the Seventies, when the momentum stalled for social progressivism, and trying to start the clock up again. It seemed providential that Harris ascended to the top of the party not long after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, and that she made abortion rights the sole substantive issue of her presidential campaign. But Harris’ attack on Biden in the 2019 debate is maybe even more revealing. Harris wasn’t actually advocating for busing — which had been deeply divisive among liberals and was essentially a dead letter after a 1974 Supreme Court decision — but she felt that it was crucial to carry the torch. She symbolised the lost progressive cause, which could finally move forward.

Elsewhere on the progressive wing of the party, the focus wasn’t so much on 1973 or 1974 but on 1980. Bernie Sanders ran his two races for the White House on a notion that the United States had made a catastrophically wrong turn with Reagan’s election. That turn pulled the plug on a social democratic system and ushered in an era of runaway capitalism and rampant inequality. Sanders, in various speeches and statements, has been completely explicit about his political chronometry. “Over the past 40 years there has been a massive transfer of wealth from the middle class and working families to the very wealthiest people in America,” he wrote in 2021. In 2014, in what would become his standard campaign pitch, Sanders said: “We have a lot to learn from Democratic socialist governments that have existed in countries like Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Norway.” The point is that the Scandinavian countries never went down the Reaganite/Thatcherite road.

It may seem surprising then that Joe Biden — the stick-in-the-mud villain of Kamala Harris’ framing — ended up, while in office, embracing a great deal of Sanders’ rhetoric and perspective. In announcing his 2021 Executive Order on Competition, Biden’s language was pure Sanders. “Forty years ago, we chose the wrong path in my view, following the misguided philosophy of people like Robert Bork, and pulled back on enforcing laws to promote competition,” Biden said from the White House. “We’re now 40 years into the experiment of letting giant corporations accumulate more and more power… I believe the experiment failed.”

Biden’s sudden adherence to a Sandersesque vision of government was comprehensible, according to the antitrust advocate Barry C. Lynn, in terms of generational memory. “I’ll admit, it’s a little funny to imagine Joe Biden as the striding guardian of liberty and light,” Lynn wrote in Harper’s. “But I’ve also long felt it somehow made sense. He is, after all, among the few politicians old enough to know where previous generations hid the key to building a fairer democracy and a better common future.”

And the centrist side of the Democratic Party, which houses Biden, has had its own fraught relations with the national dysfunction of the Seventies. Jimmy Carter, in his “Crisis of Confidence” speech of 1979, put into vivid terms the breakdown of the Great Society vision. “We’ve always believed in… progress. We’ve always had a faith that the days of our children would be better than our own,” Carter said. “Our people are losing that faith, not only in government itself but in the ability as citizens to serve as the ultimate rulers and shapers of our democracy.”

He knew that the problem was deeper than any individual issue. “The threat is nearly invisible in ordinary ways,” he said. “It is a crisis of confidence.” But, in terms of policy, what Carter actually did was to begin the dismantling of the Great Society and to pave the way for Reaganism. Historian Richard Aldous has argued that Carter can be considered “the first Reaganite”, introducing the deregulation, focus on supply-side economics, and broad tax cuts that would later be widely associated with Reagan. Carter’s mode of governance can be considered a sort of pastoral mourning for the Great Society as he was in the process of burying it. That approach didn’t work electorally, but it got a new look in the Nineties with Bill Clinton’s Third Way and his sub rosa embrace of Reaganism. The difference between Carter and Clinton was mostly tonal. Carter, for instance, committed adultery “in his heart” while Clinton did it in reality and promiscuously; Clinton buried the Great Society enthusiastically where Carter had done so mournfully.

The centrist side of the Democratic Party can be understood, then, as accepting the Reaganite turn but with a nod to what-might-have-been from a social standpoint. Hillary Clinton largely ran her race for the presidency on the notion of shattering the glass ceiling — a term that was introduced in a speech in 1978 — and that became a brutally vivid metaphor when she unwisely hosted her 2016 election night party under a glass ceiling at the Javits Center. It is a ceiling that has remained unshattered.

The Democrats aren’t the only ones who are caught in the squabbles of the Seventies. Senator Mitch McConnell — who has long been the dominant Republican figure on Capitol Hill — has dedicated his career to his “long game” of building a conservative Supreme Court. It’s a quest that has been widely interpreted as a reaction to his formative experiences with the liberal-leaning courts of the Seventies. With a conservative advantage in the Supreme Court, with Roe and Bakke overturned — and now with Donald Trump defeating Harris — the long war of the Seventies can finally be said to be brought to a close. The conservatives won, totally.

That’s a very bitter pill to swallow on the progressive side of the aisle, but in a way it may be a blessing in disguise. What it means is that the Left no longer has to dedicate itself to propping up a Great Society that has atrophied away; or to advancing progressive causes that, we now know, will never get past a conservative Supreme Court. The Left at least has the advantage of being jolted out of its time-warp and of looking at the political landscape with fresh eyes. However the Democratic Party reconstitutes itself — and it must reconstitute itself — it can do so with new faces and with ideas that speak to a very different era. The Seventies, at long last, are over.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe