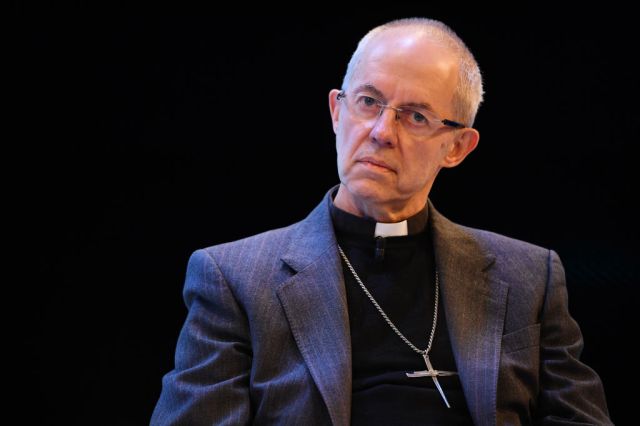

Farewell Justin Welby. (Credit: Leon Neal/Getty)

I love the Church of England. I love its liturgy, I love its glorious parish churches, I love its lack of ideological fervour, I love the gentle and inclusive way that it is porous to those outside of the Church, I love the inheritance of faith that it preserves. But things have not been well with the Church for quite some time, and the resignation of the Archbishop of Canterbury is a fork in the road. Either it grasps this opportunity for radical reform, or it will continue its slide — if not vertiginous collapse — into irrelevance.

The Church is in a desperate state. Covid was an absolute disaster. Being asked to close our churches — and to people in great need — sent a signal that we were not really there for our flocks in their hour of need. I was barred from entering my church to pray, but allowed in to check things for insurance purposes. So much for priorities. Understandably, people left in their droves. And many never came back. While the average weekly attendance in church rose by almost 5% in 2023 to 685,000, the third year of consecutive growth, we are still well below pre-Covid numbers. Might we recover? Perhaps. But it will be a struggle. Will the leadership heed my suggestions?

***

1. Burn down The Machine

Many of the clergy have burnt themselves out trying to arrest the death slide. In October, Dr Liz Graveling, senior researcher for clergy wellbeing at the Church of England, delivered a lecture to the Clergy Support Trust. The figures she outlined are staggering. More than one in five clergy is clinically depressed; one in three is mildly depressed. We are isolated, demoralised, knackered. We feel profoundly unattended to and are worried about our personal finances. As a vicar friend of mine commented with typical understatement: “It’s just not as much fun as it used to be.”

A big part of the reason for the demoralisation is the fact that, under Welby’s tenure, the Church has reinvented itself as a top-down bureaucracy. Evangelicals, like Welby, have always thought they know how to do evangelism best, because they have a number of large and numerically successful suburban churches. Welby took his big business experience, allied it to his very particular evangelical zeal, and set out to impose it on the rest of us. The churches that subscribed to the Welby formula got central funding, smaller and less evangelical ones didn’t. The problem is: what works in London suburbs doesn’t necessarily translate well to Little Snoring, or indeed inner city Leicester.

Whereas the Church was previously a model of subsidiarity — vicars were little Popes in our own parish, as detractors might say — we are now the little people fronting a burgeoning machine of impenetrable complexity. Work that was once done on the ground is now done in distant committees. Churches used to be like corner shops, all managed locally. We are now in danger of becoming a chain. It is called Vision and Strategy and comes with a whole new grammar of administrative Christianity we are now expected to know by heart.

So much of the local energy — and money — that was once spent on the ground is now taken up responding to the demands of the centre. This is what Welby and his followers call “the work”. And “protecting the work” was the reason for his initial refusal to resign. He knows the next Archbishop may well burn the whole thing down, as well she should.

2. The next Archbishop should be a woman.

Credit where it is due, Justin Welby introduced female bishops as soon as he could. He also nudged forward on gay relationships — telling The Rest is Politics podcast back in October (and I paraphrase) that his own line was now that gay sex within a faithful and committed relationship is not some great moral or spiritual crime, and that same-sex blessings should be permitted in church. But he failed to make any of this church policy. The next Archbishop needs to complete this, and make it clear that the Church does not think gay sex is sinful, indeed that it is every bit a gift from God as straight sex. Conservative evangelicals will leave the Church over this, and so be it. We cannot remain in a twilight zone between condemnation and affirmation: it drains too much energy. We have to decide.

But, arguably even more important, this should be carried out by a female Archbishop of Canterbury. Watching yet another pale, male and stale company man in a purple shirt go on Newsnight to intone the party line is more depressing than I can possibly imagine. These men, their life force drained by time spent in artificially lit offices going through the minutes of the last meeting, have been terrible at communicating the excitement and phenomenal good news of the Gospel. And over the past weeks, they have been excruciatingly inept at dealing with this existential crisis. Many of them will have to go. And we need someone who can relate and be relatable. And also, crucially, someone who is trusted to deal with the safeguarding crisis.

My pick would be Bishop Guli Francis-Dehqani, currently Bishop of Chelmsford. “I’m not so comfortable with the language of ‘Vision and Strategy’ being deployed in the church,” she confessed to a congregation at Great St Mary’s in Cambridge a few months ago. Too secular in its thinking, too obsessed with growth charts, as if the success of the Church were down to us and not down to God. And way too powerful. In exposing all this before, the Bishop had received what she described a “slap on the wrist from central church” — after which the congregation burst into laughter and applause.

More than this, though, Bishop Guli has a compelling story. Her maiden speech in the House of Lords was described by Patrick Kidd in Politics Home as “a powerful and very personal debut from Chelmsford that had several peers wiping away tears and saying it was the finest they had heard”. Iranian born, Bishop Guli comes from high end Anglican stock: her father was a Bishop of Jerusalem, her grandfather a bishop in Iran. The family was forced to leave Iran after the revolution, after which Bishop Guli’s 24-year-old brother was murdered by Iranian government agents. Someone with this kind of background is unlikely to engage in the kind of cheap moral posturing we see all too often in the Church.

And women, especially mothers, must be more trusted to deal with Safeguarding. In 2004, Francis-Dehqani stepped back from full time church ministry to look after her children. This is not what you do if you are an ambitious cleric on the make. But the deep church establishment really doesn’t want her because of her hostility to “the work”. And they will almost certainly try and block her appointment. Unfortunately for them, there is no one else of the right age on the Bishop’s bench with the gravitas and relatability to do the job.

3. No more swanning around the world

Bishops — and Archbishops in particular — are far too busy. They have an impossible job, with a fire hydrant of problems spraying across their desk. Their capacity to deal with issues is thwarted by their penchant for foreign travel. Only this year, the Archbishop made a 12-day tour to Guatemala and Central America. He had just returned from Zanzibar. Between September last year and May this year, he clocked up 48,000 air miles (while regularly preaching about climate change), including two trips to the Middle East, to New York, to Armenia, to Rome (twice). He has also been to the Congo, to Pakistan, to Gaza and the West Bank. Last week, when the crisis was swirling, he was supposed to have been in Tel Aviv with David Lammy. But the Archbishop does not work for the Foreign Office. He should prioritise the needs of the Church of England. The clue is in the name. Too busy being a global statesman, he had no time to follow up the letters he received from survivors of abuse. This is what brought him down.

Some will argue that the Archbishop is also the head of the Anglican Communion. This is true. Yet the Communion is a broken fellowship, with many thinking that the Church of England is already too liberal on matters of sex, while a third of the Communion don’t recognise his leadership. It is time, in short, for it to become a looser fellowship of Christians, each allowing the other a greater sense of — and I use the word again deliberately — subsidiarity. This was an idea actually invented by the Church, and one whose merits it has foolishly misplaced.

4. Shrink the Big Tent

Just as the theological diversity of the Anglican Communion cannot be held together by a strong centre (and so needs a weaker one), so too the Church of England has its own diversity problem. Traditionally, one of the best things about the Church of England has been its ability to include people from an astonishingly wide spectrum of theological opinion; from (to caricature just a little) deeply conservative evangelicals who take the Bible literally and warn darkly against sexual sin; to happy-clappy charismatics with their enthusiastic welcomes and unspeakable worship bands; to crypto-Catholics with their smoke and lace; to liberals who do social justice more than God. Broadly, we get along — though there are some exceptions. Liberals and conservative evangelicals really don’t get along, with the Church’s version of the culture wars still raging over sexual politics. This saps so much energy and turns the Church’s attention ever inward, which is a terrible look and contrary to the Gospel. While diversity is generally a good thing, this level of diversity is a problem. The next Archbishop must make it crystal clear that the Church of England welcomes gay people. And if you can’t cope with that, well there are other churches.

5. Lean into the weird

One of the most dispiriting things about the Welby era is the prominence it has given to church being normal, everyday, and relatable. Like a trendy schoolteacher desperate to be liked, the Church has been encouraged to think about its relevance — that achingly dull advice that has replaced the glorious other-worldly mysticism of saints and angels, Cranmer’s crystalline poetry, and Stanford in B flat, with crazy golf in the nave of cathedrals and overhead projectors. Jesus has been transformed from the Lord of Heaven and Earth, and the Judge of All, to my best mate, with all the gravitas of a crisps advert. Next year marks the 1,700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea, where Jesus was proclaimed by the Western Church as both fully human and fully divine. Christianity is by theological definition a tension between the immanent and the transcendent. In recent decades, the pendulum has swung too much in favour of the immanent — Jesus the social activist, Jesus the friendly listening ear, Jesus the comforting presence. We need to reclaim the difficult mysterious Jesus, the otherness of Jesus, the cosmic Jesus. Christianity needs to get just a little bit more weird and badass. More Caravaggio, less pastel. The Church exists to address the great mysteries of life — death, life, forgiveness, fear, passion, hope. Easy listening versions of these don’t make for a properly serious church.

***

I doubt the Church will consider doing any of this. During Welby’s tenure, the establishment has been captured by soft evangelicals, and the committee that decides the next Archbishop now has greater representation from the Anglican Communion. So Archbishop of Canterbury number 106 will be all too like his predecessor. Whatever the ructions of the Welby resignation, I fear the deck is already loaded in favour of a similar appointment: globalist and evangelical. The only way we will get the sort of person we need — and not another dreary “Vision and Strategy” company man — is for the revolution that unseated Welby to keep going. More resignations need to follow.

This, though, is simply my wish list. What I pray for. But it is not my prediction. That is best put by The Who: “New Boss. Same as the old Boss”.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe