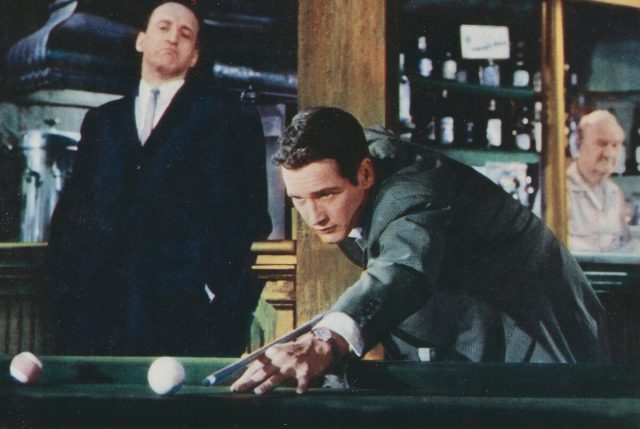

Eddie Felson, played by Paul Newman (Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

“When you hustle you keep score real simple. The end of the game you count up your money. That’s how you find out who’s best. That’s the only way.” The lines come from The Hustler (1961) starring Paul Newman, George C. Scott, Piper Laurie and Jackie Gleason. Forget about the divide between red and blue, liberal and conservative, MAGA and woke, Harris and Trump. America’s true division is between Eddie Felson (played by Paul Newman) and Bert Gordon (George C. Scott).

The movie was co-written and directed by Robert Rossen, who had been a member of the Communist Party until he broke with it in 1947. He was initially blacklisted, but then testified behind closed doors and named names. The Hustler was his first, and only, successful film after the blacklist and his testimony. It is a parable of the inextricable links between money, character, success, failure and love. American style.

“YOU OWE ME MONEY!” Bert the professional gambler, backed up by thugs, unforgettably erupts at Eddie, the pool-playing genius, at the end of the movie. Scott roars the last word out as if it were the eternal answer to an eternal question, the alpha and omega of creation itself. And that is what the movie is about: money as a finality. Not as in The Color of Money — the trite title of Martin Scorsese’s disappointing sequel. Rather, money as ontological essence; money as, to borrow Spinoza’s characterisation of it, “the abstract of everything”. Money as the consummate medium for the human desire to possess.

Eddie “Fast Eddie” Felson is a young, uncannily gifted pool player. But he’s also a pool hustler. He enriches himself by tricking other players into thinking he’s not that good. He gets them to place high bets in the expectation they will beat him, and then relieves them of their money once he’s taken them in.

Eddie, though, has his hamartia, his tragic flaw. He travels all the way from California to New York — from the kingdom of illusions to the city of grimy reality — accompanied by his shill, a middle-aged sad-sack named Charlie, to play Minnesota Fats, performed to perfection by Jackie Gleason. After playing the legendary Fats, considered the best pool player in the world, for hours in Ames, the pool room that is Fats’s domain, Eddie trounces him. He wins $10,000 — the equivalent of over $100,000 today. Charlie tells him it’s time to leave. Eddie refuses. “The pool game is over when Fats says it’s over,” Eddie snaps. Fats waits, uncertain whether the match will continue. Bert, clearly Fats’s backer and handler, has quietly seated himself in the pool room, in a chair slightly higher than the others. He says to Fats: “Stay with this kid, he’s a loser.”

Eddie doesn’t care about the money. In that sense, he is what an American is supposed to be, from the Western sheriff, to the outsider-hero private eye or cop, to Superman and Batman. He cares about being true to himself. So he looks at Bert with pain and surprise when Bert makes his comment. They continue to play and Fats ends up destroying him. Eddie is left with nothing. Wildly drunk at this point, he stumbles toward Fats with a few crumpled $100 bills and begs Fats to keep playing. Money is still the medium of his pride. Fats declines. Eddie falls to the ground, and the poolroom clears out. Bert departs, shaking his head.

Penniless, Eddie parts ways with Charlie and lives in a bus station for a while. There he meets, in the station cafeteria, Sarah (Piper Laurie), who is the movie’s moral centre. Lame, alcoholic, depressed, cultivated, sensitive, psychologically astute, Sarah lives in a small apartment alone with the elaborate lies she tells herself. She and Eddie begin a steamy affair. Sarah, who resists Eddie in various ways, falls in love with him, and Eddie, who flings himself at Sarah, clearly, if unconsciously, uses her for sex and solace until he can right himself.

The movie’s turning point occurs when Eddie, feeling restless and boxed-in with Sarah, quarrels with her and leaves. He follows his calling and goes out to hustle. But on this occasion, Eddie is antagonised by a young player who talks down to him. Eddie loses his temper. “I don’t rattle, kid. But just for that, I’m going to beat you flat.” Yet Eddie is rattled. His fragile pride is bruised. As a result, he reveals himself as a hustler too early. Just when he is about to collect his winnings, the young man’s friends force him into the bathroom and break his thumbs as punishment for his deception. Eddie drags himself back to Sarah’s, arriving on her doorstep broken and in tears.

A transformation occurs. Eddie and Sarah no longer simply eat, sleep and make love. Eddie begins to genuinely care for Sarah; Sarah drops her shield of sarcastic irony and ministers to Eddie’s inner and outer wounds. The length and fine control of human opposable thumbs are what distinguish us from any other primate. When Eddie has his thumbs broken, his pride is broken, and he is humbled in an elemental way.

For Rossen, the erstwhile communist, Eddie’s injuries make him not disabled, but profoundly human. He cannot grasp anything. This confers a deeper humanity on him in a grasping society. He becomes an ideal human type. For communists, and Christians, being broken is a permanent condition of being human. For liberals, too: the philosopher John Rawls’ famous and influential idea of the “veil of ignorance” imagines people having to choose what kind of society they would like to live in given the worst-case scenario of being a person at the very bottom — a broken person, that is to say. Most people would choose the fairest, most equal and most caring social structure.

If Rossen had indeed wanted to write a communist or, indeed, a Christian parable, he could have ended his movie right there. In a society whose cardinal acknowledgment is that everyone is broken — lame, or with shattered thumbs — everyone is protected from everyone else. Quod erat demonstrandum.

But that would be liturgy, not fiction. It would not be honest. Bert comes back into Eddie’s life and performs his own hustle. He offers to put up the money Eddie needs to make a comeback. Though in conventional Hollywood terms, Bert is a villain, it is hard to deny that he is on the side of the living. “So I got talent,” Eddie says to him at one point. “So what beat me?” Bert replies: “Character… Everybody’s got talent.” But what, the movie now asks, is the American definition of “character”?

In the event, Eddie takes up the challenge and agrees to let Bert put up the money for his long road back. Bert invites Eddie to the home of a rich Kentucky patrician to play pool during the Kentucky Derby. To Bert’s annoyance, Eddie brings Sarah.

From the beginning, Bert, the scourge of the broken, of “losers”, makes his contempt for Sarah clear. He thinks she is holding Eddie back. In fact, she is. After the patrician, Findley, beats Eddie — he plays billiards not pool, and Eddie needs time to adapt to the new game — Bert tells Eddie that it’s time to leave. In an echo of what happened at Ames, Eddie pleads with Bert to stake him more money, assuring him he knows he can beat Findley.

At that moment, Sarah enters Findley’s den and tells Eddie not to beg. She urges him to leave. “That man [Findley], this place, the people. They wear masks, Eddie. And underneath the masks they’re perverted, twisted, crippled… Don’t wear a mask, Eddie. You don’t have to.” Accepting society’s shallow conventions as the price of restoring his pride, Eddie tells her to “shut up”. He plays Findley and beats him, winning a small fortune. While he is walking back to the hotel, Bert, who has taken a taxi, allows himself to be seduced by Sarah, in part as a way of making a trophy of Eddie’s pride; he keenly envies Eddie. Revolted and shamed by her self-abasement, Sarah commits suicide in the bathroom. Arriving back at the hotel, Eddie discovers what happened and flies at Bert in a rage. The police officers at the scene pull him off.

An entire book could, and should, be written about how those Jewish screenwriters in Hollywood who had once been communists almost seamlessly assimilated communist values to Christian ones. Sarah delivers herself to Bert for the purpose of sacrificing herself, Christ-like, to the truth. Winners like Bert, she wants Eddie to know, are the true losers — but never mind that Bert survives, prevails and flourishes. Seeming losers, like Eddie are the true winners — but never mind it was Bert who taught Eddie how to stop losing. By means of her death, Sarah teaches Eddie a lesson beyond their social world. She teaches him to be a saint.

At the movie’s climax, Eddie returns to Ames and soundly beats Fats in the presence of Bert. It is the sweetest revenge for Eddie. Ever the unsentimental businessman, Bert offers to stake Eddie again, at a reduced rate. Eddie, saintlike, refuses. “Too high, Bert. Price is too high. Because if I take it, she never lived, she never died. And we both know that’s not true, Bert, don’t we, huh?” Bert reveals himself as the breaker of worlds, threatening that if Eddie does not give him his share of Eddie’s winnings: “You’re gonna get your thumbs broken. And your fingers. And if I want them to, your right arm in three or four places.”

Eddie still refuses. Bert relents and tells him that he’ll let him go unharmed. But, he warns, “Don’t ever walk into a big-time pool hall again.” Eddie is freed from hustling. He can now pursue his vocation simply for the joy of fulfilling his destiny in his work. Or as Marx put it, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

This, then, is the heart of the American dilemma. Does the true American character lie in not living like an American? In refusing to count up your money to see who’s best? Or does it lie in mastering the terms of American success? In sacrificing ethical freedom for practical liberty? Eddie might be free at the end, ethically speaking. But how does he, whose calling it is to play pool, and to hustle pool, now fulfil his destiny in his work? Now that he has thrown off his mask, how does he live in a world where wearing a mask is essential to survive? Has Sarah hustled Eddie?

As for Bert, he is still a king — the directions at the end of the script read: “Bert takes his seat again on his throne overlooking Ames, sipping his glass of milk [like the eternal American boy].” Yet he is, as Eddie has told him, “dead inside”. And Sarah was right when she told Eddie: “[Bert] hates you ‘cause of what you are. ‘Cause of what you have and he hasn’t.” Democratic envy — no individual my superior! — is sharper than a serpent’s tooth. As someone once said, you can build a throne with bayonets, but you cannot sit on it. Still, Bert is sitting on his throne.

Ethical freedom? Or practical liberty? Some will scoff and say such a dilemma is an effete fiction. Life simply isn’t so clear cut. But some might say that, as it becomes more extreme, not just in its politics, but in its everyday rhythms, American life is coming down to just that: Eddie or Bert. If everyone is indeed broken, does a politician, say, claim to be a champion of the broken ones, only to deceive them with an abstract morality? Or does a leader emerge who runs roughshod over the broken, preaching robust survival at all costs? Do you believe the otherworldly promises that the broken will prevail, or do you throw in your lot with the worldly ones, who break?

To put it another way: Who will emerge as America’s Hustler in November? The impossible saint? Or the intolerable sinner?

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe