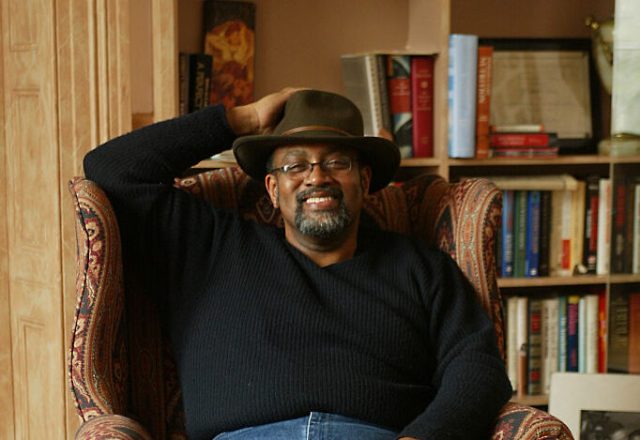

‘A bad motherfucker.’ Rick Friedman/Corbis/Getty Images

Glenn Loury, the distinguished economist and social critic, is a bad motherfucker: the bane of guilty white liberals and black race hustlers, eviscerating both with analytical precision and rhetorical prowess. He is also, it transpires from reading his memoir Late Admissions: Confessions of a Black Conservative, bad in the more straightforwardly Caucasian sense of that word.

“There’s two Tony Soprano’s,” Tony Soprano tells his therapist, Dr Melfi, in a last-ditch attempt to woo her. “You’ve never seen the other one. That’s the one that I want to show to you.” Loury similarly raises the spectre of two conflicting selves, but unlike Soprano who wants Melfi to see his good self while minimising his bad one, Loury wants to immerse the reader in the ways of Bad Glenn. Indeed, this is a deliberate strategy on his part, designed to foster the impression that he’s a reliable narrator. “The more self-discrediting information I deploy, the more credible I will become,” he surmises, echoing George Orwell’s dictum that an “autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful”. “No sane person would invent the discrediting things I’m going to tell you about myself”, Loury writes, reasoning that having shown readers his worst they will be more inclined to believe the passages that “cast me in a more conventionally positive light”.

As an academic, economist and commentator, Loury has had a long and remarkably successful career, holding positions at elite American universities, including Brown, MIT and Harvard, joining the latter as a tenured full professor at the young age of 33. As a father, husband and friend, he has been decidedly less triumphant, and much of Late Admissions is devoted to documenting the myriad lies and betrayals he inflicted on those closest to him. Indeed, Late Admissions is so remorselessly frank and meticulous in tallying up Loury’s dreadful behaviour that the reader is apt to feel like a voyeur, engrossed and grossed out in equal measure.

Over the course of several hundred pages, we learn that Loury is an absent father to his first two children; that he abandons another child that results from an affair and refuses to pay child support to the mother of that child; that he commits further multiple acts of infidelity during his second marriage; that he becomes a crack addict; that he cruises for hookers; that he has flings with his students; that he carries on with the wife of a best friend he knew since childhood; that he continues to cheat on his second wife throughout her struggle with cancer; and that he writes a mean obituary of a conservative friend (James Q. Wilson) because he thought it would make him popular among liberals. Confessions of An Enormous Douchebag would have been a more apt subtitle for Loury’s memoir.

Anyone who is prudish or puritanical should not read Late Admissions, for it is saturated in illicit sex. Loury recalls that his uncle Adlert had told him that the overriding goal in life, that what really mattered, was “to get as much pussy as you can”. Loury was in his teens when his uncle relayed this to him and it seems like he took it to heart. He has certainly had a lot of pussy, as Adlert would put it, and in recounting his many sexual conquests and romantic entanglements, he displays an almost adolescent pride, bordering on boastfulness. One of the funnier anecdotes he relates is how, when at a conference in Israel, he slopes off to an empty stretch of beach with his mistress, where after several minutes of “going at it” they draw the attention of two IDF soldiers. “A beautiful woman, an exotic beach on the other side of a great ocean, and me, the transcontinental jet-setter who made it all happen,” he writes. “To such lengths was I willing to go to in order to get what I wanted, and I wouldn’t be denied anything.”

Nor does or did Loury seem to have any misgivings about paying for sex, remembering “a wild few hours together” with two prostitutes in a hotel while away on business. “After they leave,” he writes, “I smile and think that I cannot wait to tell Adlert about this one.”

To say that Loury’s private dealings stood in tension with his public pronouncements and personae is rather an understatement. As he rapidly rose to prominence in his academic career, he styled himself as a black conservative intellectual who argued that racial inequality in America persisted not because of white racism (the “enemy without”), but rather because of pathologies within the black community itself (the “enemy within”). He was also a vocal critic of affirmative action, insisting that the problems of the black ghetto could be better managed through entrepreneurism rather than government handouts. The values he most admired were exemplified in the figure of his father, whom he revered and who’s approval he always sought: namely, “rigorous austerity and personal responsibility”. “If black people want to thrive,” he believed, “we can only depend on ourselves to make that happen.” Yet in his private life, Loury was the very personification of the pathologies he railed against publicly.

In other words, Loury was living a lie, all the while publicly donning what the sociologist Laud Humphreys called “the breastplate of righteousness” to conceal and compensate for his disreputable self. And yet he couldn’t renounce the lure of the double life, until it came crashing down when his 23-year-old side-woman accused him of assault (the charges were eventually dropped) and when he got busted for drugs possession not long after. This spelled the beginning of the end of his time at Harvard, which he traded for Boston University. It wasn’t that his colleagues there didn’t support him, quite the contrary. But he felt that they pitied him and his sense of pride couldn’t tolerate this.

Around this time, Loury sought solace and redemption in religion and began attending an African Methodist Episcopal church with his wife Linda. Although this filled a spiritual void, it wasn’t a lasting conversion. He also started to shapeshift into a man of the Left, recanting many of his earlier positions. This was quite a turnaround. Loury had been never less than trenchant in his belief that violent crime was a far more urgent problem for black people than police brutality, but now he backtracked, focusing his attention instead on the racialised evils of mass incarceration. While he once delighted in scandalising what he scathingly called the “Negro Cognoscenti” — middle-class posers who faked authentic blackness, unlike working-class Loury who grew up on the South Side of Chicago — he now went all in on courting them and professing his fidelity to the cause.

But just as things had soured with his conservative bedfellows, they too began to sour with his fellow progressives. While he enjoyed the adulation that came with righteous causes, he felt that it was a pose. “I was a conservative,” he writes, “and in truth I suspected that’s what I always had been.”

More recently, particularly on his weekly podcast, The Glenn Show, Loury has carved out a niche as a fierce and compelling critic of America’s “racial reckoning”, sternly rebuking the excesses of BLM and the sanctification of George Floyd and other victims of police shootings “as though they were civil rights heroes”. “It seemed to me,” he writes, “that the activists concerned with preserving black life and well-being ought to worry about what was going on within black communities at least as much as they worried about the cops.”

It isn’t clear why or how Loury went from being a conservative to a Leftist and then back again, and Late Admissions is not particularly incisive at explaining it. But it offers some interesting pointers. The one enduring continuity in Loury’s life seems to be his desire for contention. It’s as if he needed to unmake friends or manufacture grievances because whenever he achieved anything of worth or settled anywhere he would become interminably bored. He needed contention because of the excitement and sense of purpose it afforded him. “The real story,” he confides, “is that I revelled in playing the bad boy, in drawing the ire of those for whom I had contempt. I loved the fight.”

At the same time, Loury craves the warmth of comradeship and community, because without that where is the audience for your genius and where is the love? But he also finds community and its “we” talk and its ethical obligations a suffocating imposition on his freedom to live on his own terms. This is one of the tragedies of his life and explains much of the turbulence that defines it.

Loury’s political positioning seems more dictated by his personal needs than by strictly intellectual considerations. While his current thinking is shaped by a thread of common sense and pragmatism that has been latent in Loury from the beginning, it lacks a footing in a wider perspective about how the world is and where it’s headed.

Late Admissions is less successful at capturing the weight of Loury’s intellectual achievements, especially those that relate to economic theory. That isn’t where the energy is and Loury knows this. “I’ve always cared how it went with women and that’s taken up much of my free time,” the late Martin Amis once said in an interview, elaborating: “Even powerful figures start to dismiss what they’ve done in the public sphere. It’s the personal stuff at the very end that’s important and it gives them agony and regret and remorse. It’s a man thing.” I think Loury would more or less assent to this and much of the substance of Late Admissions bears this out.

Loury’s is now 75 and nearing the end of his life. As a young man he’d always wanted to become, in his words, a “Player of his own making”, and he has achieved that and much more. He has also played and wounded a lot of people. But at no point does he excuse or minimise this, much less try to therapise it. In the closing pages of the book, Loury acknowledges that he is a fallen man and that he has an internal enemy and that it is an indelible part of him. This is to his immense credit. Like Philip Roth, Loury suggests that we can never hope to erase the “human stain” that afflicts all of humankind. The great achievement of Late Admissions is that it confronts this head on and in a startlingly honest way.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe