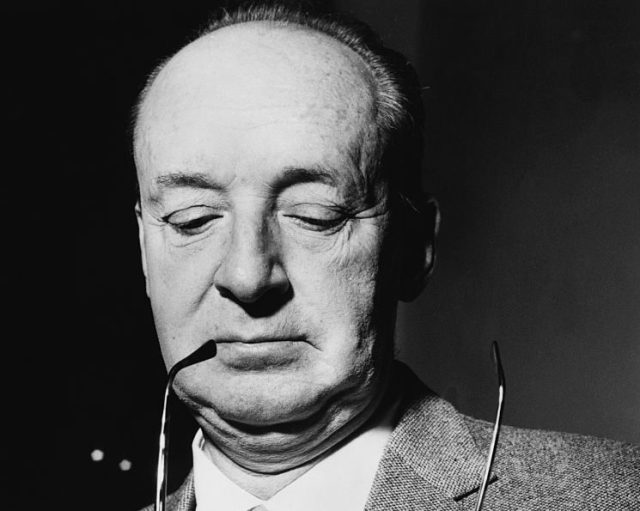

Nabokov in 1959. (Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

Pale Fire is one of the greatest books I’ve ever read. It is so great it is terrifying to write about. This is not something I would normally confess, but in this case it seems better to just come out and say it, lest the reader feel the awful stammering of suppressed terror quavering through my words without knowing what they are feeling. It is terrifying! But I want to do it anyway, because although mighty brains from all over the planet have weighed in on the subject with breath-taking and exhaustive scholarly ardour, I feel that something essential about the book remains not exactly unseen but distinctly understated.

Since its publication in 1962, people who admire Pale Fire — fawn upon it, adore it — like to speak of it as a feat of baroque intellectual magic, which it is. In her New Republic review, Mary McCarthy described it as “Faberge gem, a clockwork toy, a chess problem, an infernal machine, a trap to catch reviewers, a cat-and-mouse game, and do-it-yourself novel”, among other things. Brian Boyd, in his book Nabokov’s Pale Fire: The Magic of Artistic Discovery, writes densely and ecstatically about the novel as a near-endless array of ever-deepening “problems and possibilities”, an intellectual delight to explore; Ron Rosenbaum (in The Observer, circa 1999) declared the book “The Novel of the Century” based on the idea that it is a “theology of Shakespeare”, haunted by Shakespeare, housing Shakespeare, that it is, basically, a Shakespeare phantasmagoria. (Rosenbaum also acknowledges that the book is “an almost obscenely sensual pleasure”, but that is an aside.)

The book has also been criticised for this very virtuosity, even dismissed by those who interpret the book’s brilliance as cold, wilfully weird or even hostile towards the reader. These opposing critical opinions are sincerely echoed by readers of all kinds, sometimes simultaneously. A friend of mine described his amazed delight in the book as something he might feel “if a winged griffin had landed on [his] lawn”, awed, but not moved emotionally — and secretly suspecting that the author might consider him a sucker if he were moved. An academic acquaintance who generally loves Nabokov considers it his least wonderful book, flawed by excessive cleverness, compulsive literary cross-referencing and the homophobic portrayal of its ridiculous and bitchy queer narrator, Charles Kinbote.

It is true that Kinbote’s queerness is unflattering. (It is also not quite convincing; there is more narrative energy lavished on his dramatic woman-spurning than on his conquests of — or rejection by — men and boys.) Indeed, the generic condemnation “problematic” more than applies to the character Kinbote, a comically unpleasant personality who has been morally condemned or pitied by readers since his creation.

He appears on page one of the novel to explain that he is the editor of a poem titled Pale Fire, authored by his neighbour, friend and academic colleague, Professor John Shade, who has been recently murdered in error by an incompetent foreign agent dispatched to kill Kinbote. Kinbote, you see, is not your average college professor; that role is a disguise to hide his true identity as the fugitive King of Zembla, where he reigned as Charles the Beloved until an annoying crew of Soviet-style revolutionaries turned his beautiful world upside-down. Thus forced to take a drab teaching position at Wordsmith College in Wye, Appalachia, subletting the furnished home of a local judge (full of family pictures so distasteful to His Majesty that they are quickly consigned to the closet), Kinbote’s only consolation is his proximity to Shade who he truly admires — so much that he stalks Shade’s house to spy on him.

Whether or not Kinbote is completely crazy is a question throughout the book — indeed his very identity is a question. From my point of view, he is just somewhat crazy and a lot desperate and has certainly taken advantage of Shade’s distraught widow in order to seize control of the poem so that he may explain to the world that it really is or at least ought to have been about him and his camouflaged royalty. After his fevered introduction, written from a cheap and desolate mountain hideaway, he presents the poem, 36 pages of wry, elegiac perhaps rather staid beauty. This is followed by 228 pages of Kinbote’s wildly self-centred commentary — even the suicide of John Shade’s daughter, poor homely Hazel, with whom Kinbote feels more empathic identification than anyone else, is seen through the fanatically minute lens of His Majesty’s Zemblan concerns. And then there is the almost mystically Kinbotian index, in which detailed notes are supplied for characters barely mentioned and it is revealed that the Zemblan assassin’s name spelled backwards is the name of a “mirror-maker of genius”.

For all his fantastic humour, Kinbote seems the unintentional butt of his own jokes, the ultimate “unreliable narrator”, meant to be pitied or contrasted unfavourably with the imminently normal Shade. And yet… he reminds me of a line from Nabokov’s short story Spring In Fialta in which the narrator describes a circus poster “which depicted a red hussar and an orange tiger of sorts; curious — in his effort to make the beast as ferocious as possible, the artist had gone so far that he had come back from the other side, for the tiger’s face looked positively human”. If you replace the word “ferocious” with “grotesque” the tiger could be Kinbote.

Almost on introducing himself to us, at the beginning of his forward to Shade’s poem, Kinbote interrupts his faux scholarly description of the work with the non-sequitur, “There is a very loud amusement park right in front of my present lodgings”, before picking up right where he left off. It is one of a few small but telling oddities that made Brian Boyd, rhetorically remark: “What sort of person is this commentator?” I might answer, using a word that Nabokov would’ve hated and which I sort of hate too: a very relatable one. Someone who possesses a contemporary sensibility that feels free mixing a subjectively personal aside into what is supposed to be a scrupulous public presentation; someone who hates being pestered by loud noise when he is trying to think; someone so given to incongruous blurtings that he can be trusted to tell you the truth about himself even when he is lying.

It sounds complicated because it is. And I haven’t even mentioned the book’s most complicated aspect: the layers of patterns, linkages and intricate structure that give Pale Fire a kind of supernatural depth. The supernatural is literally a theme in the book, in the form of attempted communication between the living and the dead in weird partial words tapped out by a maybe spirit and flickering lights that show up in an Appalachian barn and are then incongruously refrained in the Zemblan tunnel King Charles traverses with one of his young loves. The colours red and green act in opposition/connection with characters and doors that link disparate times and places and the number eight; minor characters are doubled with Zemblan and Appalachian incarnations through similar names and attributes; the hiding place of the Crown Jewels is doubled as are the actual jewels; butterfly imagery links Hazel Shade, her mother Sybil and King Charles’s unwanted queen Disa — who is also linked with Hazel in a triple iteration of rejected girls.

Dates and letters also join the fun! Kinbote, John Shade and Shade’s killer all have the same birthday; Shade is killed on the day that Nabokov’s father was born and Nabokov’s father was killed by a gunman aiming to kill someone else. The family pictures that Kinbote furiously stuffs into the closet of his sublet home are all of girls named in alphabetical order — an order reversed in the names of King Charles’s possibly invented royal family. And throughout, poets and poetry star the skies of Zembla and Appalachia alike: direct and subtle references to Browning, Shakespeare, Eliot and Goethe shine piercingly or dimly in the most quotidian and/or dramatic scenes, sometimes ostentatiously quoted, sometimes so simply and quietly there that only a scholar would notice.

Only a scholar would notice most of these (and I haven’t even noted all of it), at least on the first reading; while I was aware of some of this layered patterning (the repetitive tropes of butterflies, dancing lights, opposing colours and rejected girls for example are hard to miss), I discovered most of what I’ve summarised above through critics, particularly Brian Boyd who’s book I love and recommend. Indeed the novel’s complexity has ironically unleashed armies of Kinbotes, devoting themselves to decades-long online arguments about whether or not the character John Shade invented Kinbote and faked his own death or if the reverse is true, that Kinbote actually invented Shade and wrote the poem attributed to him or — but wait! — that actually the deceased Hazel Shade spiritually transmitted the delusion of Zembla into Kinbote’s tortured mind so that he could tell her father about it and also to comfort Kinbote himself and further to create a more beautiful version of her own lonely life in his fantasy.

To refrain McCarthy: “a clockwork toy, a chess problem, an infernal machine, a trap to catch reviewers…” Except that in the context of this fantastic novel, the critic’s theories are not as crazy as they appear on paper. I don’t find McCarthy’s words entirely right; the book is more like its own living universe than anything mechanical, and in such a world (as in ours) many strange things can happen. It is designed yes, but not to trap. It matters because I think this chess game emphasis has contributed to the popular perception of the book as steroidally brainy but emotionally cold. Critics haven’t exactly ignored the book’s touching aspects: the death of Hazel Shade and her parent’s grief are given their due as is the theme of mortality and the moving beauty of the natural world. (Though I agree with Michael Wood, in his essay The Demons of Our Pity, that there is something oddly shallow about the emotion towards Hazel in Shade’s poem, not to mention an unpleasant fixation on her homeliness.) But those emotional elements tend to get lost in the critical excitement about traps and problems and creates the impression that in order to enjoy Pale Fire you need not merely an intelligent mind but a very particular type of intelligent mind, preferably one outfitted with a first-class education.

But. When I first read the book I was an ignorant 24-year-old with a barely adequate undergraduate education. Because I had not majored in English (I was concerned about what kind of job I might get after graduating and an English degree did not look promising), I had not taken many literature courses. I had read very little poetry and almost no Shakespeare. I recognised the names of the poets mentioned in Pale Fire but I could not possibly register the more subtle meanings evoked by the adjacent language because I didn’t know their work in any depth or really at all. That didn’t matter. I loved Pale Fire. I could feel its intellectual power in the intense perceptual contrasts of its characters, in the descriptions of faces and objects and, for example, the swift evocation of an alternate world in John Shade’s image of himself reflected in the window glass, “above the grass” with his furniture and an apple on a plate. I could feel it in the patterning I saw and sensed, viscerally, as if I was not only seeing a griffin landing before me but feeling the vibration of its wings come up through the ground into the soles of my feet.

But it wasn’t primarily the intellectual power that drew me in. I experienced Pale Fire far more emotionally than intellectually. I felt the emotion of longing saturating the story, the depth of Kinbote’s loneliness, the cruelty visited on Hazel and the bewilderment of her father at having lost her; I felt Kinbote’s anguish in his affected, light and giddy voice, and in the way those naturally polarised tones were electrically joined in the fast-moving comedy. (If you have read Lolita, it is a voice reminiscent of Humbert sans Dolores on a drunken drive with drunken Rita on the perpetual road to Grainball: the voice of someone broken and desperate yet mentally agile enough to bob and weave under a rain of blows, real and imagined; someone too broken and desperate to fully dissemble). The actual prose was, as Ron Rosenbaum noted, a great sensual pleasure. Then, about 200 pages in, the experience intensified when I came to this description of a secondary character, Queen Disa, the woman Kinbote/Charles indifferently marries because marry he must:

‘What had the sentiments he entertained in regard to Disa ever amounted to? Friendly indifference and bleak respect. Not even in the first bloom of their marriage had he felt any tenderness or any excitement. Of pity, of heartache, there could be no question. He was, had always been, casual and heartless. But the heart of his dreaming self, both before and after the rupture, made extraordinary amends.”

This is a narrative depth change, with no lightness or giddiness or humour. I sometimes read this section to students as an example of how a narrative can be indirectly and deeply illuminated through minor characters or descriptive asides, and no matter who they are, grad students or sophomores taking the class to fulfil a Lit major, I can feel their attention come into focus from the first two lines. Even with minimal information about who the speaker or the woman he is speaking of might be, almost any nominal adult, no matter how inexperienced, can recognise the emotional reality of those sentences that open the soliloquy.

“He dreamed of her more often, and with incomparably more poignancy, than his surface-life feelings for her warranted; these dreams occurred when he least thought of her, and worries in no way connected with her assumed her image in the subliminal world as a battle or a reform becomes a bird of wonder in a tale for children. These heart-rending dreams transformed the drab prose of his feelings for her into strong and strange poetry, subsiding undulations of which would flash and disturb him throughout the day, bringing back the pang and the richness — and then only the pang, and then only its glancing reflection — but not at all affecting his attitude towards the real Disa.”

Here, words create images to describe something that happens wordlessly, physically but subtly, in the inchoate realm of feeling. The words “subsiding undulations” which “flash” and then gradually fade (as a wave returns and fades) describe the movement of intimate emotion, the way people repeatedly draw near one another and then move away, sometimes simultaneously, in different aspects. The words also describe the bodily experience of strong feeling in a single person, rising up and then subsiding, either becoming greater or — as it is here — fading completely but for a troubling echo that lingers so faintly you can’t tell where it’s coming from. It is something almost impossible to talk about let alone write about but which almost everyone experiences. Using words to describe what is experienced wordlessly is art on a high level, at least as impressive and more affecting than even the most intricate structuring.

“Her image, as she entered and re-entered his sleep rising apprehensively from a distant sofa or going in search of the messenger who, they said, had just passed through the draperies, took into account changes of fashion; but the Disa wearing the dress he had seen on her the summer of the Glass Works explosion, or last Sunday, or in any other antechamber of time, forever remained exactly as she looked on the day he had first told her he did not love her. That happened during a hopeless trip to Italy, in a lakeside hotel garden — roses, black araucarias, rusty, greenish hydrangeas — one cloudless evening with the mountains of the far shore swimming in a sunset haze and the lake all peach syrup regularly rippled with pale blue, and the captions of a newspaper spread flat on the foul bottom near the stone bank perfectly readable through the shallow diaphanous filth, and because, upon hearing him out, she sank down on the lawn in an impossible posture, examining a grass culm and frowning, he had taken his words back at once; but the shock had fatally starred the mirror, and thenceforth in his dreams her image was infected with the memory of that confession as with some disease or the secret aftereffects of a surgical operation too intimate to be mentioned.”

The pain of unrequited love, both for the lover and the loved one who cannot return the feeling, is an obvious subject of the book as is the longing for an ideal which bleeds up through mundane reality, “the shallow diaphanous filth” vs. the fantastic colours, the dream which might be delusional or might actually be more real than acted-out life; the imagery is in effect a crumbling bridge between the two. It is in this passage that I see what I called the understated “essential something” about the book: how this elemental and raw experience is evoked as closely as possible to how it is felt, through the textures of the natural world that exist as the body exists, humbly and unknowably: plants, mountains, water, sky, light, the amazement of colours.

“The gist, rather than the actual plot of the dream, was a constant refutation of his not loving her. His dream-love for her exceeded in emotional tone, in spiritual passion and depth, anything he had experienced in his surface existence. This love was like an endless wringing of hands, like a blundering of the soul through an infinite maze of hopelessness and remorse. They were, in a sense, amorous dreams, for they were permeated with tenderness, with a longing to sink his head onto her lap and sob away the monstrous past. They brimmed with the awful awareness of her being so young and so helpless. They were purer than his life. What carnal aura there was in them came not from her but from those with whom he betrayed her… and even so the sexual scum remained somewhere far above the sunken treasure and was quite unimportant.”

A blundering of the soul through an infinite maze of hopelessness and remorse. This secondary character may be, as some critics say, a figment of Kinbote’s narcissistic imagination; she may be an alt-world creation of the deceased Hazel Shade. But whatever she is, the complex of emotions embodied in and provoked by her are real in any existing human world, as deep and for me more riveting than any problem posed anywhere else in the book. It is the mystery of human feeling/lack of feeling, the need for love and the fear of it, part of what Kinbote calls “the prison of personality” and it is not going to be solved. But here at least it is seen profoundly, with the compassionate wisdom that is the real “Crown Jewels” of Pale Fire, hidden in a description of an incidental relationship.

Of course, there are other jewels hidden elsewhere in the book, more than might be addressed within the scope of this essay. Brian Boyd quotes Nabokov remarking in relation to Pale Fire that: “You can get nearer and nearer, so to speak, to reality; but you can never get near enough because reality is an infinite succession of steps, levels of perception, false bottoms and hence unquenchable, unattainable.” The novel is a joyful and reverent mimic of such reality — and yet it invites readers and critics to come close, to find the unattainable, and so, with great gusto, they try. And I am glad that they do, even if it sometimes looks a bit like blundering through an infinite maze of some sort. I am especially glad for Brian Boyd and Michael Wood; over time, reading and learning from their intrepid analyses has deepened my understanding and respect for the book. But I still remember, as something rare and unrepeatable, the power of my first reading when I had so little knowledge and yet felt the brilliance and depth of Pale Fire almost as if through my skin. If reading this is your first experience of the book, that is what I hope for you: that you acquire a copy and see the griffin come in for a landing. If you worry that it is looking down on you, don’t. Because all you have to do is look up. Its heart is strange but it is huge; let yours beat in response.

***

Pale Fire, with an introduction by Mary Gaitskill, is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe