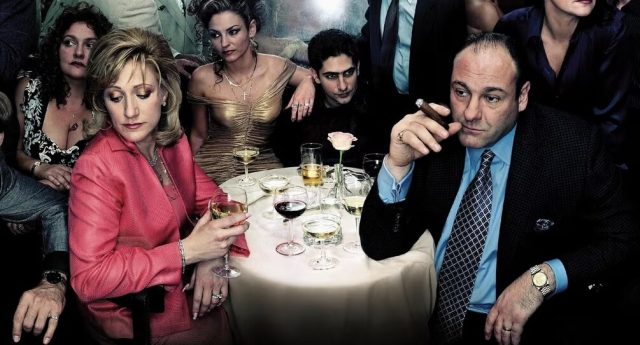

‘Tony and Carmela are trying to do something impossible, to raise a bourgeois family and inhabit their respectable McMansion just as their non-criminal neighbours do these things.’ (Credit: Allstar/HBO/Sportsphoto Ltd)

Thinking back on The Sopranos over the years, I’ve granted a sort of holy status to the scene in “Second Opinion” (Season 3, Episode 7) where Carmela is bluntly lectured by an elderly psychiatrist. She’s expecting some gentle double-talk from kindly Dr Krakower, the soft encounter with tough reality a therapist is supposed to stage for the vulnerable patient. But Krakower merely, plainly, confronts Carmela with the undeniable evil to which she’s contributing as Tony’s wife. That scene always functioned as a touchstone for me, especially the deathless moment when Carmela is force-fed this cold lesson: “One thing you can never say, that you haven’t been told.”

I’ve loved that line since I first heard it on […checks Wikipedia…] April 8, 2001. I remember it as a catharsis, the one time in the whole series when the show’s moral standpoint was clearly stated. Finally, thanks to Dr Krakower, Carmela was getting the cold reality treatment. More importantly, we in the audience were getting the cold reality treatment too, and we relished it. That line is quoted all over the internet as a — if not the — defining moment of the whole series. Carmela needed to be told it so that she might finally leave her parasite, monster, murderer husband. We needed to be told so that we might keep a clean conscience as we watched this charismatic guy do his evil thing. Being told that simple message was like an art novice finding an accurate nose in an abstract painting — a reassurance, a hint of ordered sense amid the chaos.

Except we didn’t really need to be told. We only needed to be told we were being told, because a sturdy, steady moralism informs every major element of the show. But it does so casually, organically, by letting the moral content of everyday life have its say.

Tony and Carmela Soprano know what it means to be a good person because they have models and examples all around them. They know it from impulses within themselves and from individual people in their lives and from the roles they each play as parent and spouse and friend. They want to be such people, and this wanting drives the entire show, but — and this is the simple moral lesson of The Sopranos — they don’t want it badly enough.

As we pass the 25th anniversary of the show’s revolutionary appearance in our culture, it’s smart not to get too clever about what it says. The show’s deftness in delivering its moral lessons, in other words, is of a piece with the simplicity and familiarity of their content.

It feels strange for me to praise David Chase for his light touch. I’ve always thought The Sopranos a great, great show, but when debates have come up about the Greatest Show of All Time, I’ve generally been a Deadwood guy, with The Sopranos in a close second place. I love how Deadwood takes, and makes good on, the insane gamble of reaching for beauty itself. It could have been an embarrassment, but the earnest poetry of David Milch’s dialogue is consistently perfect — psychologically revealing and politically subtle and just delightful on the ear. Fairly quickly it stops seeming a weird indulgence and becomes part of the natural fabric of the show’s reality. And Milch is the more open-hearted auteur. The horror and sadness come to us raw in Deadwood. What happens in The Sopranos, by contrast, reaches us through a conspicuous lens of Freudian irony. Deadwood is often funny, but it is a drama, historical and, despite the poetic dialogue, realistic. The Sopranos is often dark and deeply tragic, but it is — in essence — a comedy.

By this I mean that a core feature of the show is that its main characters often don’t know why they’re doing what they’re doing, and they don’t know they don’t know, while David Chase knows, and we in the audience know, and this discrepancy is a consistent comic presence. In Deadwood, Milch’s voice is audible in the decoration and elaborate grammar of the speech. In The Sopranos, Chase’s comic touch is felt, more totally and fundamentally, in what we see — Tony’s pinched face shot in grotesque closeup, Carmela’s stony profile conveying fake dignity, Silvio’s ridiculous mug surrealised in fisheye framing. Somewhat arbitrarily, I’ve held this issue of genre just slightly against The Sopranos when doing those rankings in my head. My standard seems to be that Milch is expressing an organic sensibility while Chase is deploying something that — when I look back on the series as a whole — seems a little like a gimmick.

Of course I didn’t watch The Sopranos as a whole, from a backward distance of years. I watched it an episode at a time, right when the episodes came out. In researching this article, using the arduous method of re-watching episode after brilliant episode, I was able to reacquaint myself with my original perspective on the show. From this viewpoint, what later came to seem like a Freudian (or Lynchian) gimmick looks instead like what merely happens when you mix a lucrative business of criminal violence with the strictures and ambitions of regular middle-class life. You layer family emotion and bourgeois propriety over underworld murder and vice and things will get pretty Freudian on their own, pretty fast. And these conflicts are comically and dramatically fruitful not in spite of Chase’s moralism but because of it. That is, the show is funny and filled with tension because Tony and Carmela are trying to do something impossible: to raise a bourgeois family and inhabit their respectable McMansion more or less as their non-criminal neighbours do these things. They are haunted and judged by the very life they’re trying to live. It’s no wonder their psyches wear neurotic wounds like an old ship wears barnacles, abundantly and just below the surface.

And, our reverence for old Dr Krakower notwithstanding, this conflict is not just apparent but explicit from the beginning. In the first episode and throughout the first season, organised religion and Freudian psychoanalysis and conventional middle-class morality team up to make the same point from different directions, repeatedly. Tony confesses his yearning for innocence by fetishising a family of ducks — the first of several instances where he displaces unhelpful human emotions onto animals. Carmela and her weird priest friend stage a searing living-room confession in which she scourges herself for “allowing what I know is evil in my house, allowing my children… oh my God my sweet children… to be a part of it”. All this as Tony, during a college visit with his daughter Meadow, hunts down a mob snitch, a man with his own sweet young daughter living a peaceful life in verdant Maine, and murders him with his bare hands.

But Catholic Carmela is also a modern woman. She believes in the modern church of psychotherapy. In the pilot episode, when Tony confesses he’s seeing a therapist, Carmela beams with relief and gratitude. Even as she demurs that “psychology doesn’t address the soul”, she’s clearly granting this clinical endeavour a spiritual meaning beyond its Prozac remedy for his grumpy mood. Giddily she says: “This is a start.” What’s it a start to? Well, it’s a start to something that can’t really proceed, something that can’t even get started. It’s a start to honesty and transparency, a life in which what happens on the inside roughly matches what appears on the outside.

Still, Carmela’s reaction to Tony’s news is genuine and infectious. It’s perhaps the deepest moment of marital concord in the whole series, and, as such, it provides the measure of all of Carmela’s future disappointments. Somewhat cruelly, Tony’s therapy news carries the hope that her marriage can be like the other marriages in her subdivision. But Tony is not improved by therapy, brought into contact with a better version of himself over time, where, as both wife and psychoanalyst hope, his advancing self-awareness is finally incompatible with infidelity and killing. Instead, the pressures of therapeutic discussion make him more resourceful in his evasions, adding layers to his self-deception.

It’s tempting to read this depth of badness in Tony’s character and declare him a sociopath. Even within the show, Dr Kupferberg, psychoanalyst of Tony’s psychoanalyst Dr Melfi, warns her that she’s dealing with a sociopath. Sure, Tony checks several boxes for Anti-Social Personality Disorder, but much of what we see on the show contradicts the idea that he’s deeply, truly sociopathic. Were Tony a true sociopath, someone not just violent and manipulative but lacking empathy and remorse, then much of what he does would either make no sense or simply not happen. His comic displacements regarding animals, his guilty dreaming and brooding about killing Big Pussy, his sensitivity to his wife’s criticisms, his need to defend himself against them and his raging response when she hits a nerve, his consuming need to be loved by his disapproving shrink, his desire for her to know the other, better “Tony” that isn’t part of his bloody business life — all these betoken ample stores of moral yearning and intuition hiding inside Tony’s oversized person. Were he a true sociopath, he wouldn’t need to spend so much emotional energy trying to make sense of his life as a lying, violent thug of the bourgeoisie. To a true sociopath, it would already make sense.

And if Tony were a true sociopath, his relations with his children would be very different. The show actually gives us a parent whose ways resemble those of a sociopath, his mother, and as a parent he is nothing like her. She was systematically cruel, distant, manipulative and neglectful toward her children, while Tony delights in his children, whose love for him is unguarded by any wariness about a sociopathic father’s underhanded cruelty. He’s pretty lazy as a dad, but he’s eager to satisfy the emotional claims his kids make on him. And, were he a true sociopath, he would likely resent and undermine Meadow’s achievements in school, so far beyond his own, but he happily funds and facilitates them.

The dissonance between the easy affection with which he raises his kids and the thuggery of how he makes his money is key to the show’s pathos. His relationship with his kids has much lower stakes as a clashing of archetypes if he’s already poisoned it with sociopathic abuse. Their moral vulnerability, their dwindling store of innocence in that McMansion, is much less forceful as a moral counterpoint if they’re already victims of pathological parenting. And when, as young adults, they do finally and fully ally themselves with his enterprise, when their filial love no longer functions as counterpoint and just flows into the swill of his corruption, that is a grim declaration itself, a dark change in the show’s moral atmosphere. But this story arc never happens if Tony’s fathering is sociopathic. Tony’s sisters fled their savage mother. Tony’s kids stick around.

A similar weakness dogs the claim that The Sopranos is a conventional satire of marriage and family and suburban life. If The Sopranos is a satire, then the energy behind its defining dramas is unaccountable. The psychic pressure behind its Freudian comedy disappears. The show makes no emotional sense. Alas, for many people, this interpretation is irresistible. It’s a pleasing revival of one of the dull clichés that populate the minds of Western critics and intellectuals, among whom it’s been fashionable to mock the middle classes for as long as there’s been middle classes. An article in British GQ, for example, claims that the show’s portrait of Tony and Carmela is a satire of marriage as such, and that this satire is all the more potent for how reductive it is. “As we watch… Carmela… turn blind eye after blind eye – each further betrayal from Tony papered over by another piece of expensive jewellery — we understand each flame-out is only partly about emotion and more about racketeering.” Carmela is not just salved by the gifts. She stages her tantrums to get them. She’s not sad and angry. She’s negotiating. The piece goes on: “It’s a bleak worldview from Chase, but one he sticks to: we’re all just out for what we can get, any emotion to be traded on, any betrayal a tactical advantage.”

On the one hand, the “we’re all” phrasing here is unusually crude, and as part of a claim about how actual people really are, it is straightforwardly bizarre. But, on the other, it’s usefully clear in laying out the basic structure of the satire interpretation. The notional distance between Tony and Carmela’s corrupted marriage and us is merely that: notional. In reality, “we’re all” supposedly on the make. But the gaps of perception and self-understanding that Chase so richly exploits do not exist if the background archetype, the suburban family, is also an object of satire or mockery. It’s only gripping and funny, sad and appalling, because we know what they’re trying to be — and because, like them, deep down, we know they must fail in this effort. If Tony and Carmela could reassure themselves “we’re all” the same, there would be no psychic conflicts for them to manage, no basis for the show’s surreal framing. The Sopranos would not be a Freudian comedy. And I’m sorry, but The Sopranos is a Freudian comedy.

In all this, I’m arguing against no less an authority than David Chase, sort of. In a 2021 article in The New York Times Magazine, he’s quoted as ratifying the view that the show is a parable of American decline, of which Carmela and Tony’s suburban home and subdivision are symptoms. But almost all of the larger America portrayed in The Sopranos is on screen because Tony’s crew and other Mafiosi have set themselves on some part of it, as parasites. The America we see in The Sopranos we largely see through the eyes of mobsters. Is Paulie Walnuts really a reliable diagnostician of our civic health? And much of what the article tries to portray as decline is merely evidence of change. The scene in which Paulie tries and fails to extort a Starbucks-like coffee franchise for protection money is extremely funny, and it certainly sketches a novel challenge for Mafia methods, but what this says about American decline is pretty ambiguous. This understanding of the Sopranos as a parable of decline is intellectually appealing in its pessimism, but in its details it can’t decide if the decline it’s talking about is an American thing, or just a mob thing.

David Chase may have dreamed up The Sopranos in nostalgic irritation about how much suburban New Jersey had changed since he was a kid, but in constructing it as an extended work of television art, and in giving that work a rich and complex inner life that made intimate sense to his audience, he drew on a very different set of dramatic resources. He counterposed the violence and elaborate scheming in one family with the absence of these things in the families they lived among. And he set that contrast to work. And it did work, as no other television show has worked, in no small part because it was based on differences between kinds of people that really exist.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe