Deborah Cohen & Margaret McCartney

12 Oct 2023 - 15 mins

Professor Tim Spector was one of the “winners” of the Covid era: his ZOE symptom tracker app accrued millions of users during the pandemic.

Now he has pivoted back to his true passion, gut health, and taken many of his followers with him. Endorsed by celebrities such as Davina McCall and Carrie Johnson, the new version of the ZOE app promises a personalised nutrition plan and comes with a glucose blood monitor usually used by diabetics. It is proving hugely popular, with over 100,000 subscribers paying up to £600 in their first year — and a further 300,000 on the waiting list.

It boasts all the hallmarks of a scientific endeavour, with endorsements by world-leading experts and numerous studies. But how convincing are its claims?

Deborah Cohen, a medically qualified TV, print and radio reporter, and Margaret McCartney, a GP, undertook a forensic investigation for UnHerd and found that ZOE’s scientific foundations aren’t as strong as its creators would have you think…

Read on to learn about:

- ZOE and the influencers

- Why Tim Spector created ZOE

- Does ZOE think you are healthy?

- Why ZOE wants your data

- What does your gut tell ZOE?

- How scientific is ZOE?

***

1. ZOE and the influencers

“I gave up after a month.” Gail, 49, is talking about her experience of using the ZOE app — the heavily promoted personalised nutrition plan that, we’re told, will help us understand our bodies and make us more healthy. “It certainly didn’t change my food compulsion — if anything, it made me feel worse.”

Take a look at ZOE’s lavish series of adverts, or the rapturous response to the app on social media, and you would be forgiven for thinking that Gail is an anomaly. TikTok, Facebook and Instagram are filled with celebrities, ZOE “members” and influencers sharing their positive experiences and inviting you to join the club.

One is Carrie Johnson, who recently shared her welcome email on Instagram, another is Davina McCall, one of the faces of ZOE’s marketing campaign. She claims she is now “living her best life”, telling prospective consumers (and her 1.7 million Instagram followers) that the knowledge provided by the technology is the “greatest gift ever”. A vocal menopause-awareness campaigner, McCall claims the gut microbiome is “completely different” in pre- and post-menopausal women.

Professor Tim Spector was one of the “winners” of the Covid era: his ZOE symptom tracker app accrued millions of users during the pandemic.

Now he has pivoted back to his true passion, gut health, and taken many of his followers with him. Endorsed by celebrities such as Davina McCall and Carrie Johnson, the new version of the ZOE app promises a personalised nutrition plan and comes with a glucose blood monitor usually used by diabetics. It is proving hugely popular, with over 100,000 subscribers paying up to £600 in their first year — and a further 300,000 on the waiting list.

It boasts all the hallmarks of a scientific endeavour, with endorsements by world-leading experts and numerous studies. But how convincing are its claims?

Deborah Cohen, a medically qualified TV, print and radio reporter, and Margaret McCartney, a GP, undertook a forensic investigation for UnHerd and found that ZOE’s scientific foundations aren’t as strong as they would have you think…

Read on to learn about:

1. ZOE and the influencers

2. Why Tim Spector created ZOE

3. Does ZOE think you are healthy?

4. Why ZOE wants your data

5. What does your gut tell ZOE?

6. How scientific is ZOE?

***

“I gave up after a month.” Gail, 49, is talking about her experience of using the ZOE app — the heavily promoted personalised nutrition plan that, we’re told, will help us understand our bodies and make us more healthy. “It certainly didn’t change my food compulsion — if anything, it made me feel worse.”

Take a look at ZOE’s lavish series of adverts, or the rapturous response to the app on social media, and you would be forgiven for thinking that Gail is an anomaly. TikTok, Facebook and Instagram are filled with celebrities, ZOE “members” and influencers sharing their positive experiences and inviting you to join the club.

One is Carrie Johnson, who recently shared her welcome email on Instagram, another is Davina McCall, one of the faces of ZOE’s marketing campaign. She claims she is now “living her best life”, telling prospective consumers (and her 1.7 million Instagram followers) that the knowledge provided by the technology is the “greatest gift ever”. A vocal menopause-awareness campaigner, McCall claims the gut microbiome is “completely different” in pre- and post-menopausal women.

But women only make up part of the market. Steven Bartlett, of Diary of a CEO podcast, is also an ambassador: “There’s an incredible correlation between what I’ve eaten, my blood glucose levels, and how I’m feeling,” he claims.

These three are among the 117,000 people who ZOE claims are now “members”. Another 300,000 are on the waiting list. This, despite the fact that ZOE isn’t cheap: it costs £24.99 per month (roughly £300 per year) and £299.99 for the intro kit which includes the instantly recognisable bright yellow blood glucose monitor that users display proudly.

These monitors are all part of a “personalised nutrition” plan that also measures your gut “microbiome”: the collection of “good” and potentially “bad” microorganisms in your intestines. This is assessed via stool samples which you collect in a “hammock” over the loo bowl and then post to the “lab” for testing.

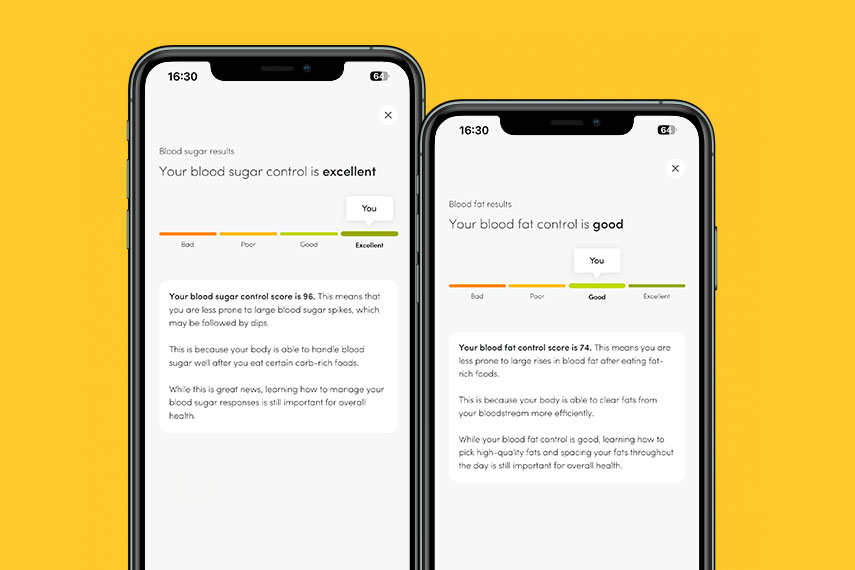

After a fortnight of continuous blood sugar monitoring, combined with your gut bug measurement, you are provided with a nutritional programme — basically foods you should eat and those you should avoid. ZOE suggests that this sort of personalised approach can help with energy levels, reduce hunger, help you reach a healthy weight, feel less bloated, sleep better, and avoid chronic health issues.

But is ZOE the solution? Certainly, its stratospheric rise is a marketing triumph. But beneath the sheen of its glossy adverts and its wealth of medical testimonies, ZOE’s scientific foundations seem far from healthy…

2. Why Tim Spector created ZOE

From its inception in 2018, ZOE has relied heavily on the profile and academic credentials of co-founder Tim Spector, professor of genetic epidemiology at King’s College London. Already a familiar name in nutrition circles, he rose to prominence during the pandemic with his ZOE Covid symptom tracker app, described by The Financial Times as “arguably the world’s largest ever citizen science experiment”. With millions logging on to share their test results and symptoms, Spector’s app, boosted by £5 million of government funding, was credited with first highlighting that loss of taste and smell accompany Covid infection.

A self-described “measured risk-taker”, Spector told The FT that he moves from subject to subject “if I’m not very interested in the next step or the next stage any more”. He started out as a rheumatologist, treating joint and muscle disorders, before turning to epigenetics, the study of how behaviours and environment can affect the way your genes work. Then, he set up the UK Twins Registry, one of the richest collections of data about identical and non-identical twins in the world.

It was this work, in particular, that led to his current interest: the interplay between diet and gut health. When he was studying the genetics of obesity in twins, he noticed that their weight sometimes greatly varied — which he attributed to the fact that their gut microbes were different.

After this Eureka moment, he decided to focus his efforts on nutrition, writing several books, the most recent being Food for Life: The New Science of Eating Well (2022). And he takes his own advice seriously — eating plenty of “fermented food” such as kombucha, kefir and kimchi to help his microbiome. He also microdoses on a diabetes drug which, he claims, could have anti-ageing benefits.

According to Spector’s website, it was during one of his presentations on his microbiome research that he met his ZOE co-founders, the now-CEO Jonathan Wolf and president George Hadjigeorgiou, both of whom have backgrounds in machine learning and business. They “shared his vision of helping individuals understand their unique biology to improve their own wellbeing in an accessible way”.

After opening offices in Boston and London, they rapidly attracted $27 million in initial funding to commercialise Spector’s work. (He remains a part-time ZOE employee and company shareholder.) And in 2019, they paid for a study that seemed to confirm the key concept for ZOE’s entry point into a crowded consumer market of products that offer advice on the healthiest foods to eat.

The PREDICT1 study suggested individuals’ metabolic responses to the same foods vary remarkably, with genes only playing a small part. (More on what you can infer from it later.) At a conference in the US, Spector revealed that they had found “really surprising” variation between certain biomarker responses — including some of those used by ZOE — to standardised meals.

It was what other investors needed to hear. The combination of a personalised nutrition app coupled with machine-learning and big data proved to be alluring buzzwords for the wellness-obsessed digital world. Steven Bartlett invested more than £2 million earlier this year. ZOE, he says, is a company that represents “the future”. It is “health science, driven by big data” that doesn’t just extend “our lifespan, but more importantly our health span”. Venture capitalists and those involved in a crowdfunding exercise thought similarly. Last year, one of the CEOs valued the company at over £209 million.

Yet some are sceptical. They suggest this is just the latest iteration of Big Diet — or Big Nutrition. “This is a classic playbook. X doesn’t work; the experts are wrong; read my book and find out the truth. Then buy my product which FINALLY fixes everything,” says one critic, who did not want to be named. Interestingly, Spector himself used to be of these sceptical voices, writing cautiously in The British Medical Journal in 2018 that observational studies — such as those since published by ZOE — are limited by the inability to measure causal relations between microbes and health traits. They can only show associations.

“The strongest level of evidence is obtained from interventional clinical studies — in particular, randomised controlled trials,” he wrote. (ZOE is yet to publish controlled trial data.) In 2019, he again suggested evidence was limited. In the same year he promoted ZOE study findings at that US nutrition conference, Spector wrote in a medical journal, that “there is a lack of long term human studies, or indeed follow-ups of short-term dietary interventions” to understand whether “diet-induced modulation of the gut microbiota endures”. Could this barrier be overcome?

3. Does Zoe think you are healthy?

On social media, it doesn’t take long to find people posting about the thrill of receiving their ZOE test results. As one user, Joel, 28, said to us: “It gives you another thing to share on Facebook or Twitter.” But how much can we actually infer about what’s going on inside our bodies?

There has long been a temptation in medical circles to assume that the more biological parameters we measure, the better. The truth, however, is that not all test results are useful. Just because something is measurable in your body, doesn’t necessarily mean that the result will yield useful information.

Dr Guess claims the app might be doing little more than recommending more fruit and veg to everyone. “They have no published data showing all this info results in personalised dietary advice,” she says. “They need to show that the dietary recommendations made by their algorithm can be replicated by other scientists. In other words, does the test give the same dietary recommendations on Wednesday as it did on Monday? This is one of the hallmarks of good science. Even more important, they need to show what they’re doing actually improves a user’s short and long-term health.”

This isn’t to say that continuous glucose monitoring isn’t useful. It is offered in the NHS, but for specific reasons — for people with diabetes. Readings can help to adjust insulin doses and improve control of potentially harmful spikes and troughs. Many people say that it has revolutionised their care. In people without diabetes, however, blood glucose is under continuous physiological control — with the pancreas regulating the release and storage of sugar in the body to keep it within normal parameters. This is the market ZOE is aiming for.

They’re not the only company making continuous glucose monitors aimed at people without diabetes. Even those in the clinical medicine arena are pivoting into this space. Indeed, The Global Wellness Institute estimates the global market segment for “healthy eating, nutrition and weight loss” is worth $946 billion a year.

The only problem is we don’t really have any evidence that these monitors do keep non-diabetic people healthy.

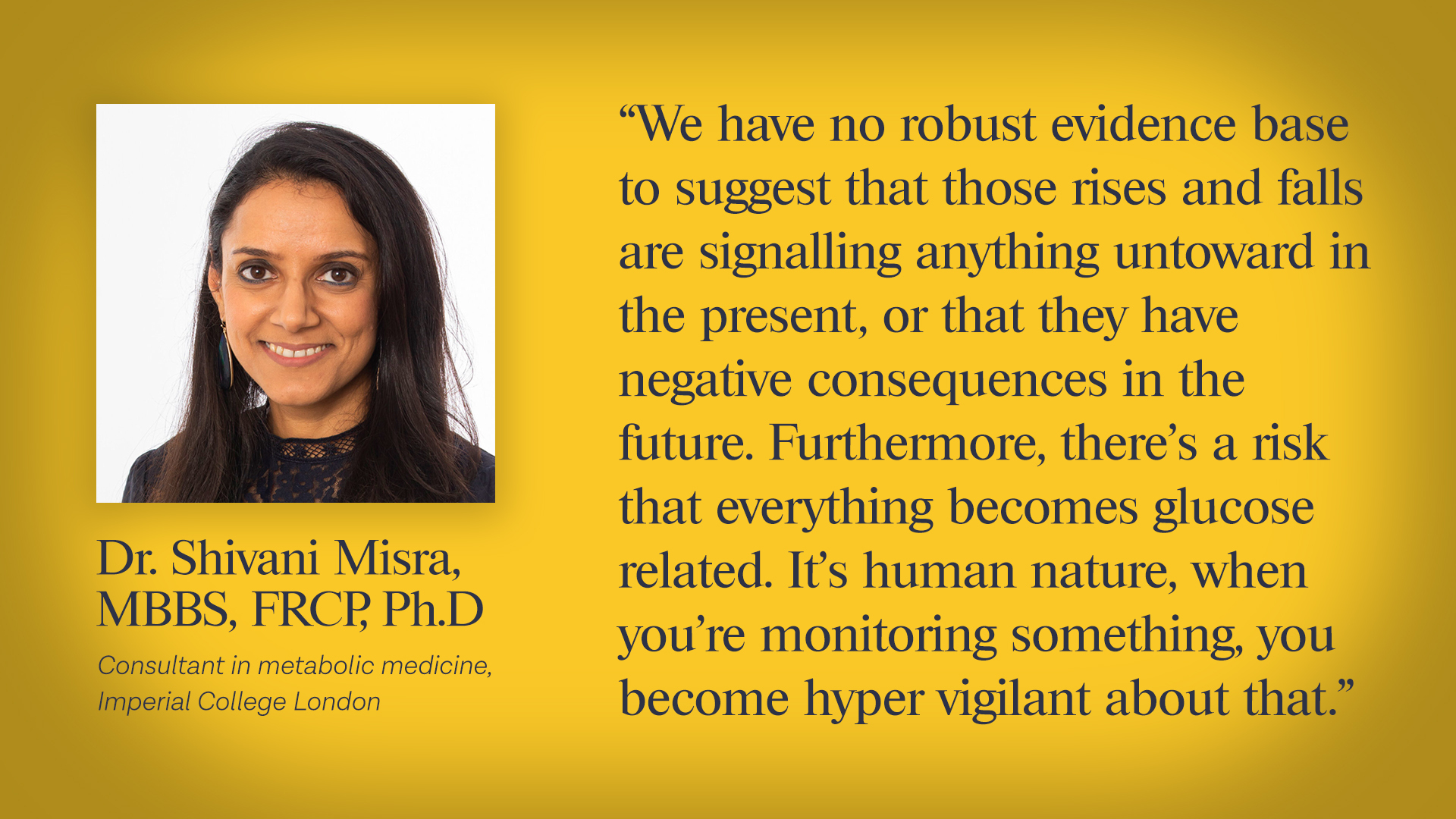

Dr Shivani Misra, a consultant in metabolic medicine at Imperial College London who researches continuous glucose monitoring, cautions that we don’t totally understand how to interpret measurements in healthy people. “We have no robust evidence base to suggest that those rises and falls are signalling anything untoward in the present or that they have negative consequences in the future,” she says. In fact, different devices might have different readings in response to eating the same meal.

Dr Kevin Hall investigates the regulation of body weight and metabolism for the publicly funded US National Institutes of Health, which has a programme in precision nutrition. His team has studied the use of continuous glucose monitoring in highly controlled environments — when people actually live at the lab for a month and undergo very specific diets and exercise regimens. They measured the glucose levels of one person wearing two devices. They found that sometimes one of the devices would give a very high glucose reading after a meal, and the other would give a low reading. They also analysed readings on the same device. They changed the regimens week to week — and concluded that the response to the same meal might vary as much as it did to eating a different meal in different weeks.

“Even in these very highly regimented kinds of controlled feeding studies, they don’t give rise to reproducible measures,” Dr Hall says. “It’s very likely that if that person ate a banana the next week, even if they had exactly the same previous food and did the same exercise that day, they might get a very different response.”

Unsurprisingly, the results are causing confusion. For instance, Gail says her glucose levels went up when she was exercising and her friend, who has diabetes and is used to monitoring their glucose, looked at her graph and thought it looked high. “I felt I didn’t get enough explanation about what this means or what might happen to my glucose,” Gail says. On TikTok, users also warn against the unwanted “spike”, saying they need to get a flatter line and describing their worries about their glucose dipping at night.

But this is not necessarily something to worry about: glucose going up and down is a normal bodily response. “Any time they see a slight rise or spike, people panic and it’s creating unnecessary anxiety,” Dr Misra says. “Then they think it’s wrong to eat carbohydrates — which release glucose into the blood — and there is no evidence that this is necessary or beneficial. Some tell me it’s taken over their life.”

But what about those who do feel their energy levels drop and notice a lethargic “crash”? Joel, for example, frequently wakes up at 3am to find his glucose dipping. He was even told he was waking up because of this dip. But he’s not entirely sure what to do about it.

This isn’t entirely surprising. While symptoms and how we feel are real, it can be hard to attribute cause and effect. In her clinic, Dr Misra sees people with and without diabetes who tell her they’re getting symptoms of low blood sugar, but when they’ve actually measured it, it’s within normal range. “There’s a risk everything becomes glucose-related,” Dr Misra says. “It’s human nature when you’re monitoring something you become hypervigilant about that.” This is something Dr Hall and his team also found in their studies. “I think the fascinating thing is that when people are provided with more and more information, they tend to make these correlations,” he says.

The risk is that we are creating problems for people rather than solving them, and turning healthy people into patients.

Ironically, perhaps mitigating this is the relationship between social class and health: in other words, the people most likely to be able to afford ZOE may be among the least likely to benefit from it. Because of this, Amitava Banerjee, professor of clinical data science at University College London and consultant cardiologist, says that ZOE plays into what is called the “digital divide”.

“Even when digital interventions are useful, the people who need them least are usually accessing them most, especially given the cost,” he says. “Those who are at the highest risk of health problems are often in more deprived and ethnically diverse areas, with neither the money nor the resources to use ZOE.” And even though it’s been largely tested on young healthy people of European ancestry — as the ZOE team has written in medical journals — the marketing goes beyond this cohort of people. “The results they get from studies might not be applicable to people outside that group,” Professor Bannerjee cautions.

Elsewhere, some doctors have turned to social media to complain about the increased workload the app is creating for them among a cohort known as the “worried well”. GPs have described to us how they’ve been contacted by patients concerned they have diabetes, as they think that is what their continuous glucose monitors are showing. While ZOE is just one of dozens of private companies and influencers who generate blood results capable of causing alarm and sending patients to NHS GPs, they all add pressure on appointments — especially if people didn’t get good enough information about what the test results actually mean.

5. What does your gut tell ZOE?

Blood sugar is only a part of what ZOE tests. Other indicators as to the function of our metabolism and how we respond to food is determined by our gut microbiome. Zoe wants to harness the “potential power” of this to affect your long-term health and certain symptoms, and so takes a reading on how good your “gut bugs” are with the help of your stool sample. A diet plan to improve that is then constructed.

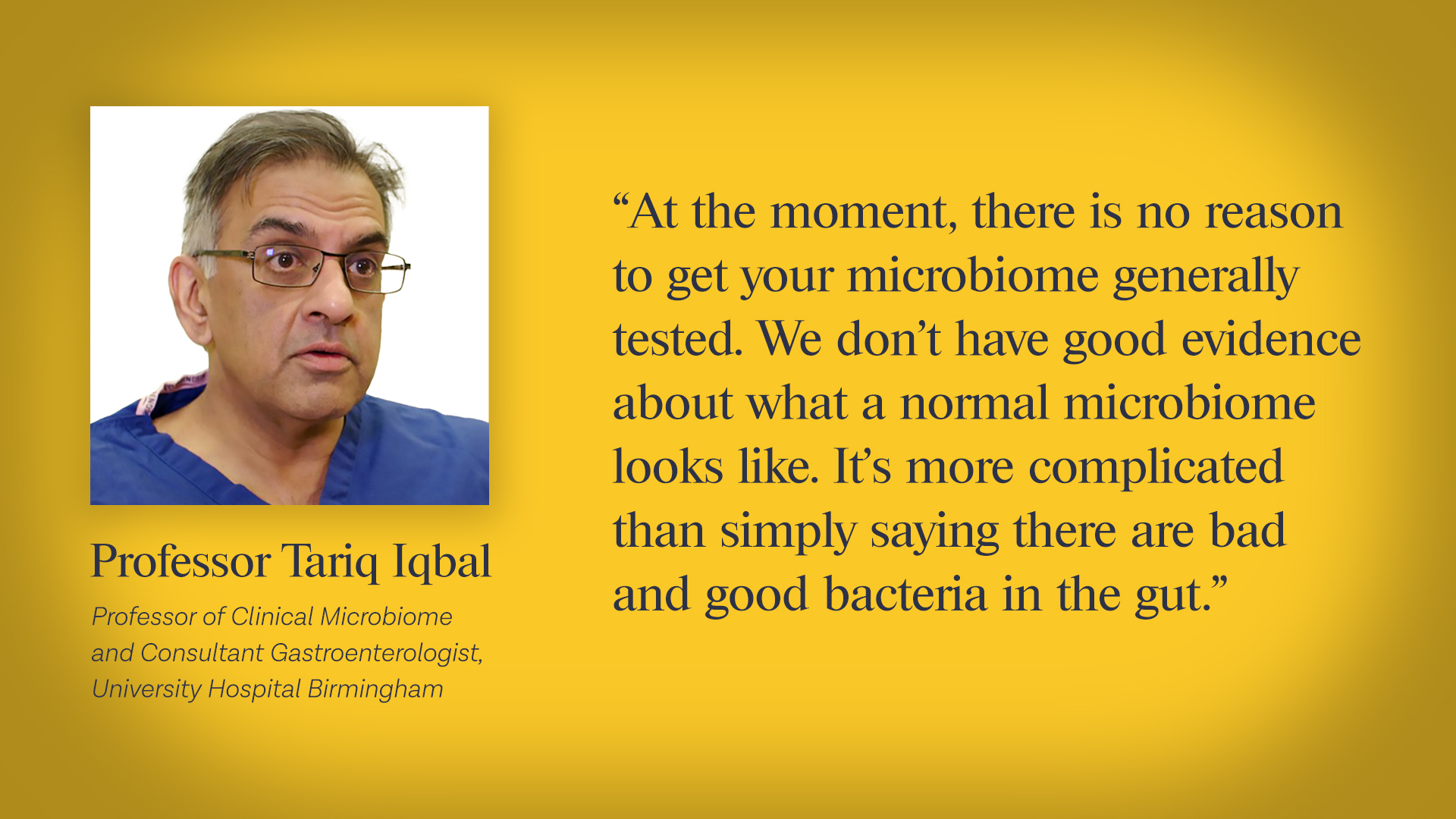

But not everyone is convinced there is sufficient scientific evidence to justify this approach. Dr Hall says research suggests you can change the microbiome in pretty consistent ways across individuals by changing their diet. “The complexity of the microbiome kind of belies a single readout of good versus bad. How you even come up with a single good, bad kind of criteria is mystifying to me,” he says.

Professor Tariq Iqbal, a gastroenterology consultant who runs trials into faecal microbiota transplantation in people who have bowel disorders, says that we’re only just beginning to understand to what degree levels of microbes naturally fluctuate in the gut in a healthy person over time. “At the moment, there is no reason to get your microbiome generally tested,” he says. “We don’t have good evidence about what a “normal” microbiome looks like. It’s more complicated than simply saying there are ‘bad’ and ‘good’ bacteria in the gut.”

Current research suggests that there is no “standard” microbiome composition that can be used as a baseline for health. There may also be problems with reading too much from a single sample. According to Guts UK, a digestive disease charity that works closely with the Gut Microbiome for Health Group of the British Society of Gastroenterology, the bacteria found in your stool does not necessarily tell you what microbes are in your gut. Meanwhile, the British Dietetic Association warns: “Commercial gut microbiota testing and lifestyle change programmes based on the test results cannot be advised currently as the science is not at a stage that can support testing and treatments programmes.”

Nor, Dr Guess adds, is there any robust evidence to support the claim that personalising a diet based on the gut microbiome is more effective than generic healthy eating advice for any of the claims being made. In fact, Professor Iqbal says that patients might be unnecessarily worried by what microbiome testing shows. “At the moment, we just do not have enough knowledge to safely and accurately recommend any specific interventions (such as particular changes in diet, and/or particular probiotics) to cause beneficial long-term changes to the composition of the bacteria in the gut,” Guts UK said.

ZOE, however, told us that their data showed members “who follow ZOE advice, including gut booster foods, see an improvement in their gut microbiome score” — the mix of “good” and “bad” microbes. This conclusion is drawn from a ZOE internal survey of 450 members who followed their advice for more than 12 weeks, which also showed 70% have more energy, 85% improved their gut health and others saw improvements in their menopause symptoms. This is all heavily promoted across their website.

These results haven’t been published and they declined to share it with us when we asked, so we are unable to assess what was asked or how the sample was selected. Moreover, as Dr Guess points out, “the data has not been validated or peer-reviewed”. Neither was there a control group, which would be needed to know whether it was ZOEs’ specific advice, or simply better healthy eating, that was making a difference. When we relayed this to ZOE, they agreed this meant that we could not be sure these were “clinically meaningful results” and told us they were going to be publishing a randomised controlled trial in the future.

It is hard not to be blown away by the dizzying array of high-profile journals that feature on ZOE’s website: Nature Medicine, The BMJ, The Lancet, among others. It links to abstracts of papers published in peer-reviewed journals, which on the surface seem to provide proof of the science. At a closer look, however, not all is as it seems.

ZOE places the weight of their programmes’ claims on three main studies with the acronym PREDICT (Personalised Responses to Dietary Composition Trial). They were carried out with scientists from prestigious universities, including Stanford, Harvard and Kings’ College, London. They have not yet all been published.

The studies analyse the results of people making multiple readings about their body and food intake. This has produced a huge dataset: more than 4 million glucose readings so far, for example. These findings are then used to develop models to predict the impact of particular foods on our bodies — all valid areas of study. The researchers have searched for associations between different measurements, such as hunger and types of food eaten.

All of which sounds impressive. Until you realise that these were observational studies, which can only show associations between various data collected, and not causations, as Tim Spector himself has previously noted. For while measuring lots of variables to find patterns can be a useful research technique, it also means you increase the chances of finding coincidences — which puts you at risk of misinterpreting random variation as a meaningful difference. Poor practice in this type of study is known as “data dredging”.

Nor do they answer the key question: is there evidence that the individualised advice generated by the ZOE tests, which is the key market differentiator, does what it claims?

The answer: we don’t know. There have been no trials published exploring whether the “personalised” advice given by ZOE can result in better health outcomes compared with standard diet and lifestyle advice.

And the same holds for menopausal women, the key ZOE demographic targeted by Davina McCall. The first PREDICT study in 2022 compared data in pre, peri and postmenopausal women. According to ZOE: “Women who have been through menopause had, on average, higher blood pressure and blood sugar, a greater risk of developing cardiovascular disease in the next 10 years, worse sleep, and more body fat. Crucially, the team’s analysis found that diet and the bacterial species that were present in women’s guts were at least partially responsible for the changes.”

However, Dr David Nunan, Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine at the University of Oxford, is sceptical. “It’s a cross sectional [observational] study” he says, “which means that no claims of causation can be made.”

The design of the study, in other words, simply isn’t capable of telling whether any changes in the microbiome are a result of menopausal change. In fact, Dr Nunan says, “when the data for all microbiome species are compared, there is no statistical difference in pre and postmenopausal women. It’s only when you examine a subgroup of species that 8 out of 2,452 show a statistically significant difference.” Moreover, even when this happens, the study has not indicated what this means in real life. In other words, we do not know what impact this has for the ways that women metabolise food.

Yet despite these gaps, ZOE told us that they are “proud” to have recently completed their own randomised controlled trial “with a non-personalised control group versus the ZOE programme”. The full manuscript, they say, is “under preparation”.

According to its critics in the science community, however, even this trial has its design flaws. One group receives the whole ZOE package, the other receives a leaflet with US health advice. But the way it is set up, people will know exactly which group they are in, thereby rendering results less reliable. A fairer test to assess is its ZOE’s personalised algorithm that makes the difference would be for both groups to receive blood monitoring and stool analysis, and what they thought was personalised advice. The only difference should be that one group receives advice based on ZOE’s tests and algorithms, while the other receives advice that looks like it might be “personalised” but isn’t.

“You have to bear in mind when looking at these studies that they aren’t fully independent,” Professor Banerjee says. “They are marking their own homework. You need external validation and testing to reproduce the results.”

None of this is to say that paying close attention to nutrition is not important. ZOE is only one of hundreds of apps that measure our biometrics in this age of the quantified self. But while keeping abreast of our data might be interesting, are these promises of personalised advice based on sound medicine? And are they, as the website promises, scientifically proven to lead to real-world improvements?

Without this evidence, Zoe is simply collecting our data and then selling it back to us. And not only does this come at a financial cost — it could be making us less healthy.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe