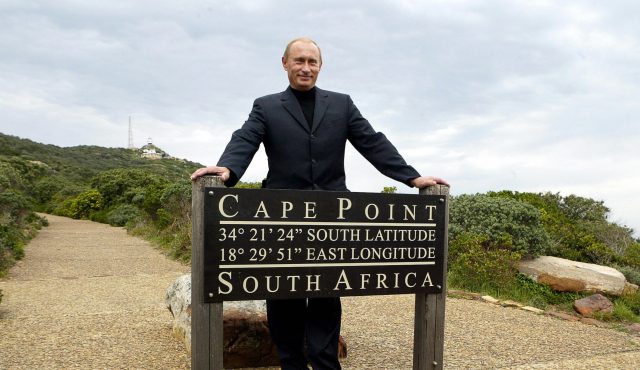

Vladimir Putin visits Cape Town (GIANLUIGI GUERCIA/AFP via Getty Images)

When the 15th annual Brics summit gathers in Johannesburg next week, the vaunting hope of the five invested countries will be that the group finally begins to show some of its initial promise. The host, South African president Cyril Ramaphosa, will have even more limited ambitions: that the summit burnishes his relations with a globally isolated Russia, and diverts attention from the faltering state in which the three-day event is to be held.

The Brics acronym was coined more than two decades ago by Lord Jim O’Neill, formerly Goldman Sachs’s head of global economic research, and it has stuck — unlike the initial expectations for the group. Only this week, O’Neill himself suggested that the collective of emerging economies — Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — has not “achieved anything since they first started meeting”.

Yet the aggregate numbers remain impressive. Jointly, the group holds $4.4 trillion in reserves. Its New Development Bank (NDB), a counterpart to the World Bank, is capitalised at $100 billion, and the Brics Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), equivalent to the IMF, also stands at $100 billion. Between them, Brics countries are home to more than two-fifths of the world’s population.

Despite this success, Brics members disavow any competitive or confrontational aspirations against the developed world in general, or the G7 in particular. Sotto voce, they make it clear they regard themselves as the new kids on the block, emphasise their common purpose and extol their bountiful resources. Look deeper, however, and one finds more conflicting sub-agendas in Brics than the group lets on.

First, the two biggest players, China and India, are prickly neighbours. Apart from the ongoing 60-year border dispute that has claimed hundreds of lives, the two are highly competitive in developing world countries, particularly in the Indo-Pacific region, and are certain to clash at this year’s summit over China’s ambitions to expand the group to bring in more “non-aligned” members. Twenty-two states have formally applied to join, among them Iran, Argentina, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. India — which, in terms of GDP, would beat France, Italy and Canada to a seat at the G7 — wants to keep things reasonably tight.

Second, embattled Russia hopes to use the Summit to push its own agendas, primarily garnering developing-world support for its imperial ambitions in Eastern Europe and driving a de-dollarisation of the international financial markets, possibly through some form of Brics currency. This might seem a forlorn hope in the short term, but it’s perhaps obliquely attainable in the distant future, through the strengthening of the Chinese renminbi against a weakening dollar. Again, India, alarmed by Russia’s putschists methods in Africa and locked into deep market relations with the US and the Middle East, is unlikely to be convinced. The absence from the meeting of Russia’s president Vladimir Putin, because of the possibility of arrest under an International Criminal Court warrant (he is expected to appear by video link), indicates exactly how embattled his country’s position is.

Third, the Brazilian and South African governments will likely pursue a narrative aimed at creating an ostensible “non-aligned” lobby in world geopolitics, inside or outside the Brics group, that is, in reality, an anti-America front, something that may become too confrontational for India’s liking. They hope, perhaps erroneously, this will play well with the punters back home. Yet the duo is unlikely to be making any of the big calls: Brazil and South Africa’s combined shareholding in Brics, if measured by nominal GDP, amounts to 7.3%; South Africa is at 1.62%, which is perhaps why O’Neill has always argued the country should not be part of the club at all.

Lastly, the Brics are divided on key issues of energy policy. Resource-poor India and China favour alternative energy systems. Russia and South Africa are prodigious producers of coal, and, in the case of the former, oil.

So, what does Ramaphosa hope to gain from this gathering of fraternal yet deeply wary confreres? He certainly hopes to use it to add weight to his public argument that, regarding the Ukrainian war, there is a middle way between blind support for the United States and Europe on the one hand, and Russia and its silent sponsor, China, on the other. Amid a resurrected Cold War, he wants a resurrected “non-aligned” movement — or, to use the buzzword, “Global South states”.

Few in the developing world would disagree with the objective; many feel the US has acted badly in attempting to lead-pipe third-party nations into picking sides. But Ramaphosa also seeks to use the Brics Summit to promote Africa, to advance Russian interests in Africa, and to divert focus from the multiple self-induced crises that confront him at home. Sixty-nine heads of Global South states, including all African heads of state but no developed world ones, have been invited as “observers”.

The extent to which African leaders respond to the invitation will be a guide to some key questions: the attraction of the Brics option, the resilience of US influence in the Global South, increased Russian and Chinese activity in Africa and, lastly, the status of Ramaphosa himself at both home and abroad. His vulnerability, ironically, may well be his chumminess with Russia.

The nature of South Africa’s relations with Russia hardly needs rehearsing: its persistent refusal to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the holding of joint naval exercises with Russian naval forces, clandestine arms trading between the countries, and the unhealthy predominance of Russian oligarchs financing the perennially cash-strapped ruling African National Congress. Ramaphosa was also instrumental in organising a quick-fire “peace mission” to Ukraine and Russia in June, with seven rounded-up African heads of mostly minor states. He was also front and centre in the recent Russia-Africa Summit in St Petersburg, though attendance by African heads of states was down — 17 this year, compared to 43 at the Sochi 2019 Summit, which had heralded Russia’s new and ardent embrace of Africa.

As his gofer efforts continue to be coolly received by the majority of African leaders, Ramaphosa’s Russophile position runs the risk of sidelining him and South Africa from the doyen position that the country and its president has always assumed since liberation. Indeed, if India has claims to a place at the G7, Nigeria has an even greater claim to Africa’s seat at Brics: its GDP is now larger than South Africa’s.

Samuel Ramani, in his new book Russia in Africa, intensively tracks Russian post-Cold War engagement in Africa. The theme of that diplomacy, although sometimes erratic, is a long-term strategy: patience in ambition, opportunism in deployment and lupine in execution. “By combining counterinsurgency operations, arms sales, autocracy promotion and soft-power tools, such as media outreaches, educational diplomacy, debt forgiveness and humanitarian aid, Russia could remain an attractive partner for African countries and preserve a unique niche between France, the United States and China,” he writes.

The target countries for such attention share certain disfiguring features: fragile states under weak leadership, volatile internal politics, collapsed national institutions, despairing polities, emigrating elites, biddable security services and vacuums created by the departure of agencies once able to guarantee sovereign stability. To these tottering autocratic regimes, Russian Private Military Companies (PMCs) make an offer they cannot refuse: private security support to maintain power in return for control or shares in mining operations and preference in infrastructural contracting.

Since its renewed interest in Africa in 2019, Russia’s fingerprint can be seen wherever there is existent chaos: in Libya, Burundi, Congo, Central African Republic, Guinea, the Sudan and, most recently, in Niger. This is particularly true in the Sahel and Maghreb, where the West’s reckless and naïve support of the Arab Spring in 2010 destroyed stable autocratic regimes and left a mishmash of theocratic zealots, bandits and irredentist nationalists, opening the way for the independent and muscular Russian PMCs such as the Wagner Group, with its billions of dollars in revenue from its mining and oil operations in Africa and the Middle East. A Blackwater on steroids, Wagner is dangerously independent and ferocious. In asymmetrical warfare, they offer their clients something the judicialised military of the West cannot: brutal, indiscriminate efficiency.

The involvement of Wagner in coup or counter-coup activities on the continent has raised huge concern among African leaders, most recently in the Niger coup which the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) vows to crush. But curiously, and damagingly, President Ramaphosa — known here as “Cyril the Silent” — has not taken a firm public position on Wagner, despite the fact mercenary activity is outlawed under the African Union’s Covenant on Mercenarism, effective since July 1985. Indeed, one of Ramaphosa’s predecessors, Thabo Mbeki, was the driving force behind its implementation and instrumental in closing successful white South African mercenary operations across the continent following the democratic transition in 1994.

After its bizarre, two-day quasi mutiny in June, Wagner’s role as Putin’s stormtroopers in Europe appears to have run its course. It now proclaims that Africa is its future, another troublesome legion consigned to the farthest part of an empire. Thinking South Africans, watching the complex forces at play in their Brics summit, conscious of the fragility of their nation and alert to the possibilities of tumult at the elections next year, pray that they remain out of reach.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe