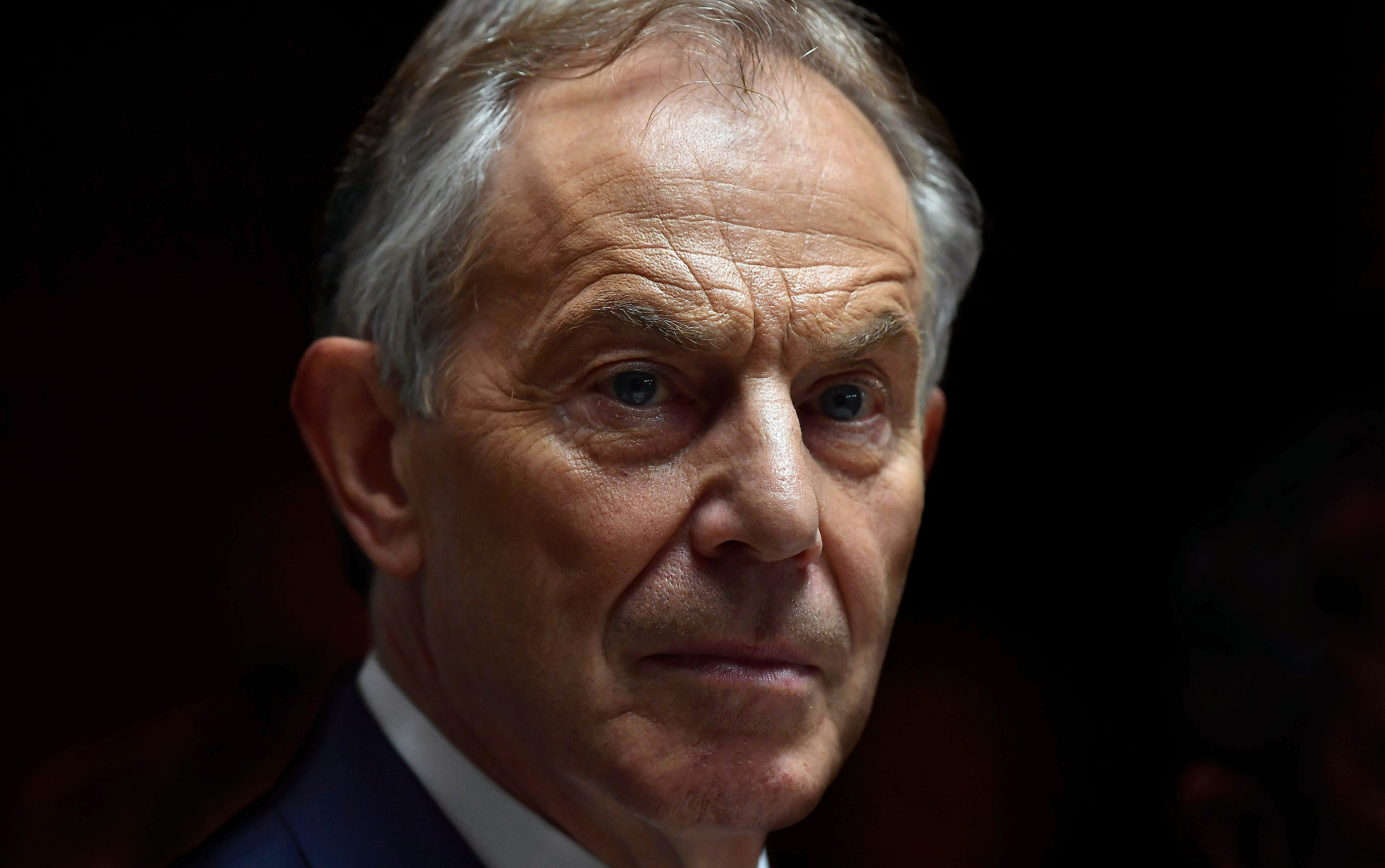

Blair has created a world in which he remains powerful (Aïda Amer)

Tom McTague

August 7, 2023 19 mins

I

At the end of every week, Tony Blair receives his “box” to review over the weekend. It is no longer the tatty, old red briefcase of a Prime Minister, but a virtual one accessible from his laptop wherever he is in the world. Yet, the process remains much the same as when he was in Downing Street. Those who work for him must submit their papers before the box is closed for the weekend. Blair will then review the documents and add comments before meeting his team the following week. Only those really close to the former PM can email him papers directly.

Such is the life of Blair in “retirement”. Aged 70, he works with the zeal of a man with something still to prove; something to build; something perhaps to redeem. Constantly travelling, Blair spends as much as 70% of his time abroad: raising funds, attending conferences, giving speeches and networking with world leaders, plutocrats, corporate executives and “thought leaders”. He flies on private jets and is escorted in armed cars with security always close by. This is Blair today: no longer Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, but Prime Minister of Tony Blair Inc.

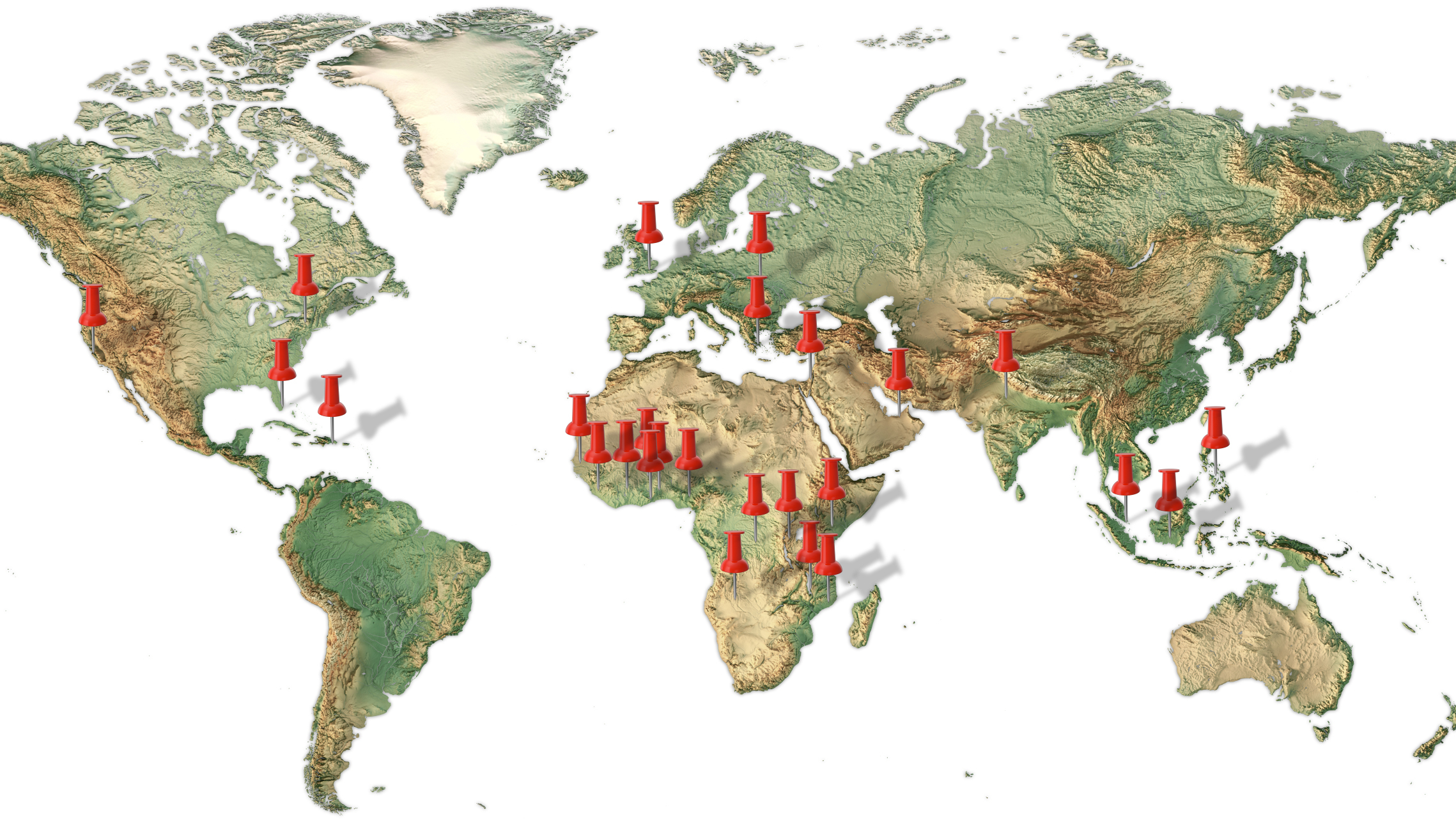

Formally, he is “executive chairman” of the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, known to all as the TBI. The institute was born in 2017 and now employs more than 800 people worldwide, some with salaries as high as $504,000 (though Blair does not take one). He has offices in London, New York, San Francisco, Abu Dhabi, Singapore and Accra, and enough money to stage the slickest political conference in Britain. He has a media team to manage his media “grid”, a policy team to shape national debate, and a delivery team to project-manage his priorities across the world.

Working directly for him, Blair has a chief executive who used to work in No. 10, Catherine Rimmer, a global managing director who once worked for Justin Trudeau, Michael McNair, and an executive vice president who sits on the board of Oracle, one of the world’s biggest tech companies, Awo Ablo. His policy unit, meanwhile, is the only think tank in Britain with American levels of funding and a direct line into both the Government and Opposition, not to mention the Commissioners in Brussels and tech titans in San Francisco.

It is this arm of the TBI which has produced policy papers on everything from Brexit to AI to Covid. Its influence is such that cabinet ministers and even prime ministers — including Boris Johnson and Liz Truss — are regularly in touch. Starmer’s agenda as Labour leader now so closely resembles the policy prescriptions put forward by the TBI, whether on the need for a closer relationship with Europe or a new planning regime, that there is talk throughout Westminster of a Blairite reconquista. He has openly offered his institute to help Starmer if he becomes prime minister.

I

At the end of every week, Tony Blair receives his “box” to review over the weekend. It is no longer the tatty, old red briefcase of a Prime Minister, but a virtual one accessible from his laptop wherever he is in the world. Yet, the process remains much the same as when he was in Downing Street. Those who work for him must submit their papers before the box is closed for the weekend. Blair will then review the documents and add comments before meeting his team the following week. Only those really close to the former PM can email him papers directly.

Such is the life of Blair in “retirement”. Aged 70, he works with the zeal of a man with something still to prove; something to build; something perhaps to redeem. Constantly travelling, Blair spends as much as 70% of his time abroad: raising funds, attending conferences, giving speeches and networking with world leaders, plutocrats, corporate executives and “thought leaders”. He flies on private jets and is escorted in armed cars with security always close by. This is Blair today: no longer Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, but Prime Minister of Tony Blair Inc.

Formally, he is “executive chairman” of the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, known to all as the TBI. The institute was born in 2017 and now employs more than 800 people worldwide, some with salaries as high as $504,000 (though Blair does not take one). He has offices in London, New York, San Francisco, Abu Dhabi, Singapore and Accra, and enough money to stage the slickest political conference in Britain. He has a media team to manage his media “grid”, a policy team to shape national debate, and a delivery team to project-manage his priorities across the world.

Working directly for him, Blair has a chief executive who used to work in No. 10, Catherine Rimmer, a global managing director who once worked for Justin Trudeau, Michael McNair, and an executive vice president who sits on the board of Oracle, one of the world’s biggest tech companies, Awo Ablo. His policy unit, meanwhile, is the only think tank in Britain with American levels of funding and a direct line into both the Government and Opposition, not to mention the Commissioners in Brussels and tech titans in San Francisco.

It is this arm of the TBI which has produced policy papers on everything from Brexit to AI to Covid. Its influence is such that cabinet ministers and even prime ministers — including Boris Johnson and Liz Truss — are regularly in touch. Starmer’s agenda as Labour leader now so closely resembles the policy prescriptions put forward by the TBI, whether on the need for a closer relationship with Europe or a new planning regime, that there is talk throughout Westminster of a Blairite reconquista. He has openly offered his institute to help Starmer if he becomes prime minister.

And yet, it is not the policy unit that is the TBI’s driving force, but its consultancy operation. Today, the “government advisory work” is responsible for almost all of its revenue, bringing in $79.4 million of its $81 million turnover in 2021, according to the latest accounts. In a recent round of internal restructuring, this side of the organisation was prioritised, resulting in a number of policy specialists leaving, including the policy unit’s leading man, Ian Mulheirn. (When we approached the TBI a spokesman insisted policy making had not been “de-prioritised” and remained one of the three pillars of the institute’s work, alongside “strategy and delivery”.)

The consultancy arm, meanwhile, is expanding rapidly, offering advice to governments around the world on the art of “delivery”. Look at the TBI’s recruitment page and there is an extraordinary array of jobs available: four in Abu Dhabi, three in Eastern Europe, two in each of the Philippines, Rwanda, Athens and Côte d’Ivoire, and one each in Israel, Indonesia, Kenya, New York, Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana and Miami. Meanwhile, its offices in London, Singapore and Delhi are all expanding.

The TBI has become, in the words of one figure who knows the institute well, a “McKinsey for world leaders” — a global consultancy business which advises governments on how to govern, while also acting as a middle man between the world’s political and business elites. Astride it all, of course, is Blair himself, the man who decides what the organisation should focus on, who it should help and where it should expand. Like a senior partner in a law firm, Blair brings in the clients, using his connections with the rich and powerful.

It is important to stop for a moment to appreciate just how mould-breaking Blair’s post-premiership life really is for a British politician. When Margaret Thatcher resigned as prime minister, she joined the House of Lords. When John Major left office, he became chairman of a cricket club. Gordon Brown became a UN special envoy, David Cameron took on various chairmanship roles, Theresa May and Liz Truss remained in parliament and Boris Johnson returned to his old life writing newspaper columns. None of them tried to build anything on the scale of Blair’s globe-spanning TBI, a British “Clinton Foundation” combining philanthropy, business and political influence. Blair has assembled something so big, in fact, that according to one figure close to another former prime minister, he has approached at least one of those who succeeded him in No. 10 to see if they might be interested in working with him.

But the question I keep coming back to is: why?

II

At Blair’s Future of Britain conference in July, I watched as he weaved through a packed drinks reception, glass of water in hand, posing for selfies, imparting his wisdom. I hoped to grab a word. But such was the scrum of acolytes and security, I could not get close.

As Blair worked the room, hugging old friends and granting quick audiences to starstruck Labour MPs, it felt like being back in the early 2000s. For many of my generation, Blair will always be a defining politician. For me this is doubly so; I grew up in Sedgefield, his constituency, and knew him, tangentially, through my parents who were both Labour activists. I knew all those who worked for him and, indeed, spent time in his constituency office myself as a wide-eyed work experience kid. Back then, Blair seemed almost the ur-politician, the archetype others copied to win power. To this day, seeing him still feels a little bit like journeying back in time.

I am not the only one who thinks this. One person who worked at TBI, and has since left, compared life inside the institute to the movie Goodbye Lenin — in which a woman who fell into a coma before the fall of the Berlin Wall is shielded from the truth by her protective son. Blair’s new life, according to some former colleagues, feels like one long prime ministerial cosplay in which everybody must play their part. There is the media grid, the box, the police protection officers, armoured cars, private jets and constant meetings with world leaders and VIPs. Spend a day in the TBI offices in central London and you might see anyone popping in: a leading Indian politician one day, Bill Clinton greeting his old friend with a bear hug the next.

Yet there are plenty of giveaways that time has not stood still: the grey hair; the suede Chelsea boots which are a shade too informal for frontline politics; the Apple Watch poking out from under his jacket. The truth is that Blair is only just emerging from a period of his life when public animosity meant that he rarely ventured out in London and, indeed, felt more comfortable not just out of the city but out of the country itself. Looking back, it is astonishing how quickly his reputation fell after leaving office.

Blair resigned as prime minister in 2007 with high hopes for his new life. He was given a standing ovation as he left the House of Commons for the last time and was immediately confirmed as the new “Middle East envoy” representing the UN, EU, US and Russia. There was hope he could do for Israel-Palestine what he had done for Northern Ireland. The tides of history, however, were no longer with him. By the time he left the envoy job in 2015, peace in the Middle East was further away than ever.

During this period, the world Blair had tried to build as prime minister seemed to collapse all around him. Soon after the financial crisis, which immediately followed his resignation, Blair lost his bid to become the first permanent president of the European Council, the stain from Iraq just too great. And then his old rival Gordon Brown ordered an independent inquiry into the Iraq War — a trial Blair could neither win nor escape.

This was when he set up the basic structure of his life today, creating a number of charities in the areas of policy he was most interested in: the Tony Blair Sports Foundation in the North East of England; the Tony Blair Faith Foundation which worked across the world; the Tony Blair Africa Governance Initiative focused on development. He also set up “Tony Blair Associates”, his consultancy business. To begin with, each of these organisations were nominally separate, which meant most of the attention went on the business wing, leaving the impression that he was simply hawking his services among a range of unsavoury governments — from the Kuwaitis to the Kazakhs — to the highest bidder, his post-premiership life one primarily driven by money-making.

Fair or not, the fact that Blair was evidently making a lot of money did not sit well with a public who had been thrust into a world of austerity immediately after he left office. He had swiftly taken a well-paid seat on the board of JPMorgan Chase and joined the lucrative speaking circuit. This work brought in enough money to allow him to swap his old constituency home Sedgefield for two multi-million pound properties: one in London and another in the Home Counties. It did not go unnoticed that he seemed to be recreating the life he had in No. 10, only now freed from having to care about public opinion. His Georgian townhouse in London looked just like Downing Street and his country retreat was not only near Chequers, but had the same air of Chilterns grandeur.

Taken together, the money-making nature of his post-Downing Street life almost destroyed Blair’s public image. Even his decision to give away the entire £4.6 million advance for his memoir, A Journey, was dismissed as a publicity stunt.

But then came Jeremy Corbyn, Brexit and Donald Trump — the populist revolt. This was the moment his resurrection really began. Brexit, in particular, replaced Iraq in the public consciousness as the defining political event, with a new set of political villains whom the public could boo and whistle.

This period of political turmoil, according to many I spoke to, shocked Blair into becoming more involved in politics again. Blair took an important step towards rebuilding his public image by merging all his business and charitable interests into one organisation — the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. From this point on, instead of having a consultancy business and several charities, Blair presided over one giant not-for-profit organisation.

In 2017, he set up a unit called “renewing the centre”, recruiting a team of smart, young Anglo-Americans to come up with ideas to save the liberal order, as they saw it. From the beginning, though, there were tensions in the team. Some believed that given Blair’s background as Labour leader, “renewing the centre” meant, in effect, renewing the centre-left, finding new policies that would rebuild the coalition of progressives he had once so successfully amassed. Others, though, saw it differently. For them, “renewing the centre” meant renewing both the centre-left and the centre-right, and even forming an alliance where necessary to defeat their existential enemy: the “populists” who must never be appeased. I was told Blair was firmly in the latter camp.

For some, he was drawing exactly the wrong conclusion, confirming the populist narrative that there was no difference between the traditional parties, and that neither of which would allow any real change to the system. Over the years that followed, some of Blair’s more Left-leaning recruits departed in frustration, believing, as one person put it, that Blair was not really any different from George Osborne when it came to austerity. Others said the tensions in the project ran even deeper.

“It was really fraught,” said one. “We were trying to save democracy — but from Mayfair.” Could the TBI really learn lessons this way? Another simply said: “It was a failure.” At this time, Blair was devoting much of his energy to campaigning for a second referendum — a fight he would eventually lose in December 2019, when Boris Johnson comfortably defeated Corbyn’s Labour with the promise to “Get Brexit Done”. The centre was collapsing.

And yet, from this point of political impotence, Blair’s reputation and influence has recovered. As the pandemic began to spread across Europe the following year, Blair put his policy unit to work. As cases escalated, the TBI released paper after paper on everything from face masks to mass testing and even international vaccine passports, always seemingly one step ahead of the Government. When the country was desperate to be vaccinated, Blair released a paper calling for a delay between the first and second doses to improve efficiency. The Government quickly announced the same plan.

Finally, Blair seemed to be back in touch with the zeitgeist. The pandemic was an ultimate test in apolitical “delivery” — that what matters is what works. He was back. His institute was flying and donations were beginning to pour in from around the world. But under the surface, all was not well.

III

In his memoir, A Journey, published in 2010, Blair describes how he helps developing countries. First, he hires teams of “highly qualified young people” from “Governments, the World Bank, McKinsey or private banks”. Then, after hiring these bright young things, he sends them out into the world to “build capacity, so that in time the locals can do it”.

Over the past few years, Blair has rapidly expanded his team of consultants. In Africa alone, the TBI is active in Rwanda, Senegal, Nigeria, Mozambique, Togo, Ivory Coast, Malawi, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Teams of TBI experts sit at the heart of foreign governments, advising on everything from how to improve crop yields to the creation of “presidential delivery units”.

A quick look at the description for its “Country Director Eastern Europe” job gives an indication of the kind of work the institute does. “The Country Director will lead a TBI team embedded in country at the highest level of Government,” the advert reads. One of its key responsibilities is to “build and maintain a relationship of trust with your counterpart (typically President or Prime Minister level)”. In doing so, the candidate must be able to “suggest and convince your counterpart on key development priorities that TBI could be supporting”. What would be the reaction if this was the other way round: if, say, the Clinton Foundation, advertised for a team of people to be embedded in the British government or simply to “suggest and convince” the British prime minister to follow their advice?

Yet the TBI is proud of what its teams have been able to achieve . “In Nigeria, our energy advisor worked on the design and implementation of a mass solar-connection programme called Solar Power Naija that aims to provide electricity access to 25 million Nigerians,” the report states. In another example, the TBI said it “supported the government of Burkina Faso to improve the country’s agriculture and agri-business outcomes”. In doing so, the TBI claims, they helped increase the country’s “fertiliser-blending capacity”.

To the TBI’s critics, this is just the gloss of “deliverology”, the belief that what is really holding a country back is not so much deep structural challenges such as corruption, economic exploitation or colonialism — but bad governance. And this can be fixed. The problem, in other words, is largely technocratic, not political.

Another criticism levelled at Blair is that what he is really doing is advising on how to build a version of the Downing Street he created 20 years ago — right at the very moment the British state has shown itself to be so woefully dysfunctional (something, ironically, Blair also believes).

But it’s not just cynical Brits who are questioning the effectiveness of the TBI. There are also plenty of raised eyebrows in Africa. In June, Nigeria’s Guardian newspaper published an op-ed by an academic which dismissed Blair as a “self-serving lobbyist… projecting dubious altruistic inclinations”. Nigeria, it said, must not “willingly [offer] itself as a cheap financial rehabilitation home for retired British Prime Ministers”.

In Malawi, there is similar public disquiet. The TBI first arrived in the country in 2012 soon after the former president Joyce Banda came to power. However, after Banda’s government was overwhelmed by an extraordinary corruption scandal known as “Cashgate” — in which it emerged that as much as $250 million had been looted from public funds after a junior civil servant was found with $300,000 in cash in the boot of his car — the TBI left.

It returned to the country, though, in 2020, after Lazarus Chakwera, its new president, took over and asked for help to “strengthen its delivery and implementation mechanisms”. Not everyone in Malawi was happy about it. Charles Kajoloweka, executive director of the human rights and governance watchdog Youth and Society, said it was almost impossible to to find out exactly what TBI was doing. William Kambwandira, executive director at the Centre for Social Accountability and Transparency in Malawi, agreed. “Our greatest concern is that government dealings with the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change have been kept under wraps.” In a statement, the TBI said the “sole purpose” of its work was “to ensure the government is delivering on its commitments to improve the public services it provides to its people.”

Such criticisms get to the heart of why some are sceptical about the TBI’s modus operandi. The TBI offers technocratic support based on a technocratic assessment of development, but it does so to political leaders often based on personal relationships with Blair himself.

The former Malawian president Banda explained how her relationship with Blair worked. “When I ascended to power, he and his wife Cherie flew over to Malawi within one week of my presidency,” she told UnHerd. “When he came over, during a state banquet hosted in his honour, I had a conversation with him where I personally requested [support] and he offered to send over three of his staffers to help me, due to the fact that I had assumed the presidency abruptly. I remember that is when he told me about his global programme and offered to lend me a hand. I remember what he said: ‘I have several people working in the region and I will shift them around.’” As Banda put it: “There was no formal agreement or big ceremony because he was just helping a friend.”

IV

In April 2022, Blair needed someone to manage the TBI’s vast, global consultancy. He hired Mike McNair from McKinsey, a Canadian who had worked for years as Justin Trudeau’s policy chief in Ottawa. Since arriving, McNair has overseen a rapid expansion of the organisation.

The nature of this expansion, however, raises questions about the TBI’s future and how it is funded. There has been a push from the TBI to access philanthropic donations and to create partnerships with business. One relationship in particular jumps out from the TBI accounts: that with the tech billionaire, Larry Ellison, and his company Oracle.

Ellison, 78, is currently thought to be the world’s fourth richest man, with an estimated fortune of $140 billion. Like many tech billionaires, he has cultivated a reputation as something of an iconoclastic sage, a workaholic visionary who can see the future more clearly than others — and, importantly, deliver it. Like his friend Elon Musk, Ellison is known for his almost impish impatience, his mind moving from one grand projet to the next, often making grand claims about their revolutionary potential only to move on to something else soon after. “I am a sprinter,” Ellison once remarked. “I rest, I sprint, I rest, I sprint again.”

It should not have been a great surprise, then, when in 2020 Ellison announced that he was suddenly disbanding his entire team at the Larry Ellison Foundation in London. The unit was led by Matthew Symonds, the former Economist journalist (and father of Carrie Johnson) who wrote an “intimate” authorised biography of Ellison, published in 2003. When I rang Symonds, he immediately hung up.

Ellison’s decision to close his London operation came at the height of the pandemic, announcing that he wanted to focus all his charitable energies on “medical philanthropy”. In many ways, this made perfect sense. Ellison bankrolls the Ellison Institute for Transformative Medicine, focused on trying to find cures for cancer.

At around the same time, Ellison began deepening his relationship with Blair. In partnership with the TBI, Ellison’s Institute for Transformative Medicine created a “Global Health Security Consortium” with scientists at Oxford University to provide “support for leaders around the world to help them prepare for the health-security challenges of tomorrow”. Ellison also began giving more and more money to the TBI. In 2019, the Larry Ellison Foundation gave the TBI $10 million with a further $20 million committed. By 2021, this had risen to $33 million, with plans for future donations of a further $49 million.

At some point, Blair was evidently able to convince Ellison that the TBI’s methods were a more effective way to make the world a better place than his previous efforts. And the partnership between the two does have a certain logic. Blair believes that “the power of technology” must be harnessed by bringing together politicians and “innovators”. This, then, is one of the central purposes of the TBI as Blair sees it: to act as a matchmaker for plutocrats such as Ellison and political figures such as himself. But it is an approach that raises awkward questions about power and transparency.

Alongside the Global Health Security Consortium, the two of them have also created a “Tech for Development” programme. The idea is to help developing countries build “comprehensive digital infrastructure”. Together, Blair and Ellison have rolled this out in Ghana, Rwanda and Senegal for free, with a view to building electronic health records so that governments know who is vaccinated and who isn’t.

Not everyone, however, looks so kindly upon the partnership. Ellison, after all, is a divisive figure. To some, he is an intense visionary in the same mould as Musk, with the same intense desire to conquer all in business. As Symonds writes in his biography, Ellison has an “unquenchable optimism and almost messianic self belief”. And he is not shy about it. During the pandemic, Ellison offered his medical research facilities to President Trump free of charge. He has bought an island in Hawaii which he uses as both an ultra-exclusive resort for the rich and a living agricultural experiment, part of his grand plan to secure global food supplies. Even as he approaches his 80th birthday, he is still dreaming of his next great breakthrough as well as his legacy. Perhaps that’s why, last year, he made one of the biggest gambles of his career.

In June 2022, Ellison bought the electronic health record company Cerner for almost $30 billion. It was the largest buy-out of his life. Almost immediately after the purchase, Ellison announced that it would help him realise his aim of building a single national database for health records. The plan was endorsed by Blair. His hope is that, using Oracle technology, every American will be able to store their medical data online. It is a visionary move, which, if it pays off, would make Oracle the Amazon of health records. To some, the partnership with the TBI makes good philanthropic and commercial sense: if Oracle can show that digital health records work in Africa, why not elsewhere? And by partnering with the TBI, Oracle gains access to parts of the world it might not have been able to reach before.

The problem is that such a scheme to create a single national health record database is not only incredibly complex and hard to deliver, but extremely contentious. In fact, the main objection is not technocratic, but political — even moral. Do we want every health record to be stored on a cloud run by one corporation? Oracle is already facing a lawsuit in the US over claims it has unlawfully collected information on 5 billion people.

Whether you see the partnership between Blair and Ellison charitably or otherwise, it reveals an important reality about today’s world and the way power works in practice. Blair and Ellison operate in a sphere of hyper-connected individuals (one board member, for instance, is Baroness Rona Fairhead, Boris Johnson’s former minister for trade and export promotion). They talk and meet each other regularly, making important decisions that affect the lives of many people, in ways which are far harder to scrutinise than those taken by governments and political leaders.

Others I spoke to said it is not possible to judge Blair’s enthusiasm for this technology without acknowledging the fact that his institute is partially dependent on donations from a tech billionaire. Some of those who have previously worked closely with Blair went further, arguing that the conflicts of interests within Blair’s new life go even deeper, extending into the heart of the organisation itself. One arm of the TBI might be writing papers on how to protect the international liberal order, for instance, while the consulting arm is embedded with illiberal governments who pose a challenge to that very same order.

Rather than hide this, the TBI actively advertises its partnerships with business, arguing that the “partnerships” it has built up, alongside the donations it receives, allow it to do “the great bulk” of its consultancy work at no cost to governments. When it comes to tricky questions such as patient privacy, Blair is adamant that they do not undermine the transformative potential of technology. In Malawi, for example, the TBI boasts of its partnership with Musk’s “Starlink” internet service, which helped hundreds of thousands of people left homeless by a cyclone. Blair’s entire vision today is for governments to become more effective by linking the kind of strategy, delivery and policy units he had in No. 10 with the kind of technology that was not available to him. Just as he wanted to introduce ID cards back then, he now supports digital ID cards today, as well as vaccine passports and vast new health databases to tackle the spread of disease. As Blair sees it, his partnership with Oracle is just pragmatic policymaking.

But like Ellison, Blair is something of a utopian futurist. He believes, almost as a faith, in the power of technology. Blair is a good boss, according to many I spoke to, because he is always so upbeat and energetic, but when it comes to technology he is a little too “naive” about its possibilities. Another former employee suggests he is “fatalist” about technology in the same way he was fatalist about globalisation — not thinking critically enough about its risks and political consequences. The greatest irony, though, is that such wide-eyed belief in technology now feels almost old-fashioned. To a younger generation who grew up in a world dominated by Big Tech and Big Pharma, the dominance of giant corporations run by tech plutocrats feels less utopian than dystopian.

V

When Blair left office, he consoled himself with the thought that his life was not over. As he wrote in A Journey, he’d always had a bigger passion than politics: religion. Religion gave him purpose. “There is so much frailty still to overcome,” he concluded in his memoir. “But in overcoming it lies the meaning of life.”

But what are these frailties Blair must overcome? According to Catholic teaching, “sins of frailty” are minor acts committed through “indecision, weakness, lack of vigilance or courage”. Those who have previously worked closely with him see a bit of all these in Blair. Some believe he too often shies away from conflict, even today. In No. 10, he outsourced being the bad guy to Alastair Campbell and did not confront and demote Gordon Brown soon enough, which undermined his premiership. Some believe Blair is now shying away from confronting Starmer, a man he believes will become prime minister, but, according to a number of people I spoke to, not a sufficiently reforming one. Even as Blair battled to save centrism, he was careful not to burn bridges with the Trump or Johnson governments, or indeed any of the illiberal governments he works with.

Is this is a sign of indecisiveness? It is striking that even those who most like and respect him are unclear what exactly he wants from the TBI. Does he really want it to be the McKinsey for world leaders? Or a think tank? And for what purpose exactly? To Blair, this type of thinking is overly reductive. To have a political impact you must have policies and the ability to implement them. But it is also for this reason that there is what one former employee described as a certain whimsy to the TBI — an organisation less committed to the service of an abstract goal than to the aspirations of Blair himself. If Tony wants something, it happens; if he wants to help someone he helps them.

The more I studied him, the more I wondered whether his biggest frailty of all is simply the desire to remain relevant, the frailty that J.D. Salinger once described as, “not having the courage to be an absolute nobody”. Blair was a somebody once and it is very difficult to give that up. He had power to do things and he still wants to do things — and so he needs power. But to get power you need money and connections and ideas and people. And he now has all those things in droves.

This is the reason he continues to work as hard as he does, taking his box home at weekends, raising money, flying around the world, attending conferences. Maintaining the network becomes an intrinsic goal in itself. This helps explain why Blair takes meetings with world leaders and works for countries many would avoid. He has what one person described as a deep, primal need to be “connected”.

Today, Blair lives the life of a prime minister, but with the freedom to shake off the petty realities of government, working on campaigns to help American governors one moment, flying in to help embattled African leaders the next; all while working on grand plans to change the world with exciting, utopian tech bros in California.

But how much of this is actually real? “Do governments really want his strategic advice,” one person who knows Blair put it to me, “or his phone number?” Do those companies he has partnered with really have only altruistic intentions? And do political leaders really only work with him to make their governments more effective? The truth, I suspect, lies somewhere in the ambiguous soup of human motivation; in the flawed, frail characters of ordinary human beings with conflicting aspirations, trying to do good in the world and for themselves.

Blair today is more influential than any other former prime minister: he has built an empire that connects business to power and himself to everyone. In the 15 years since he left office, Blair has created a world in which he might not be prime minister but he remains powerful. And that is the point. The power is the point.

Additional reporting: Jack McBrams

Tom McTague is UnHerd’s Political Editor. He is the author of Betting The House: The Inside Story of the 2017 Election.

TomMcTague

TomMcTague

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeExcellent investigative journalism by Tom McTague and Unherd. I didn’t hear anything that surprised me but it’s important to put some substance behind the widespread suspicions about Tony Blair and his institute (and Ellison’s philanthropy, and the Clinton Foundation, and Soros, and the Gates Foundation, and…yeah, it’s a long list).

Sort of a redundant comment really, but I’m always stunned by the hubris and self-regard by Blair and his like. Somehow they think it’s their appointed role to set the fate of mankind.

…..without the tedious/tawdry business of getting elected, or dealing with the little people.

…and thus sowing the seeds for the populist revolt which encourages the likes of Blair to get back into politics again.

The term “vicious circle” honestly doesn’t do the phenomenon justice.

I take it you regard ‘populist’ as a pejorative term.

‘She in glass houses, shouldn’t throw stones’

I take it you regard ‘populist’ as a pejorative term.

‘She in glass houses, shouldn’t throw stones’

…and thus sowing the seeds for the populist revolt which encourages the likes of Blair to get back into politics again.

The term “vicious circle” honestly doesn’t do the phenomenon justice.

…messianic self regard.

Do as I say, not as I do and be grateful for me helping myself up the greasy pole whilst making lots of lucre for myself and my friends.

Before his sharp exit BEFORE the inconvenient Iraq report came out he spent his time networking and working the room with his Davos style pals and is reaping the rewards now.

A shadowy man doing shadowy things.

It’s unreasonable to mix in the Gates Foundation with these talk-and-do-nothings. Gates has saved more lives in 20 years than the entirety of Africa’s governments and the West combined.

With polio vaccines that spread polio?

With polio vaccines that spread polio?

I agree. The truth is that he is going nowhere and is just a part of the New World Order which ultimately will bring suffering to mankind. They are swimming in trillions and are able to bribe all and sundry to get in line. It is our choice to resist it or not.

So true. Look at his inh inhuman attack on Iraq and his never apologizing despite huge Street demonstrations. A narcissist big time

…..without the tedious/tawdry business of getting elected, or dealing with the little people.

…messianic self regard.

Do as I say, not as I do and be grateful for me helping myself up the greasy pole whilst making lots of lucre for myself and my friends.

Before his sharp exit BEFORE the inconvenient Iraq report came out he spent his time networking and working the room with his Davos style pals and is reaping the rewards now.

A shadowy man doing shadowy things.

It’s unreasonable to mix in the Gates Foundation with these talk-and-do-nothings. Gates has saved more lives in 20 years than the entirety of Africa’s governments and the West combined.

I agree. The truth is that he is going nowhere and is just a part of the New World Order which ultimately will bring suffering to mankind. They are swimming in trillions and are able to bribe all and sundry to get in line. It is our choice to resist it or not.

So true. Look at his inh inhuman attack on Iraq and his never apologizing despite huge Street demonstrations. A narcissist big time

Excellent investigative journalism by Tom McTague and Unherd. I didn’t hear anything that surprised me but it’s important to put some substance behind the widespread suspicions about Tony Blair and his institute (and Ellison’s philanthropy, and the Clinton Foundation, and Soros, and the Gates Foundation, and…yeah, it’s a long list).

Sort of a redundant comment really, but I’m always stunned by the hubris and self-regard by Blair and his like. Somehow they think it’s their appointed role to set the fate of mankind.

“He flies on private jets and is escorted in armed cars with security always close by.” This is regular behaviour for crime bosses.

Was he ever convicted of burying the report which told of Blair ignoring advice from top people when, in 2000, led by the EU, he decided to proceed with his plan to get motorists to change from petrol to diesel. Apart from costing motorists £billions, it has probably damaged the health of many and possibly caused deaths. Blair knew that although petrol had higher levels of CO2 , diesel had far higher levels of noxious particulates, which were far more damaging to individuals. If these people were directors of commercial companies they would have been jailed for negligence!

P J Browne

Thank you for this information! I had no idea that it was Blair behind the DIEsel scandal!! I will investigate this. I use the example of the diesel scam to wake people up to various nefarious “net zero” schemes and scams that will undoubtedly lead to excessive harm to human beings. There is no conclusive proof that climate change per se will negatively affect the human race (in fact there may be many positive effects) but there IS conclusive proof that actions taken by greedy, power-crazed technocrats WILL!

Thank you for this information! I had no idea that it was Blair behind the DIEsel scandal!! I will investigate this. I use the example of the diesel scam to wake people up to various nefarious “net zero” schemes and scams that will undoubtedly lead to excessive harm to human beings. There is no conclusive proof that climate change per se will negatively affect the human race (in fact there may be many positive effects) but there IS conclusive proof that actions taken by greedy, power-crazed technocrats WILL!

Was he ever convicted of burying the report which told of Blair ignoring advice from top people when, in 2000, led by the EU, he decided to proceed with his plan to get motorists to change from petrol to diesel. Apart from costing motorists £billions, it has probably damaged the health of many and possibly caused deaths. Blair knew that although petrol had higher levels of CO2 , diesel had far higher levels of noxious particulates, which were far more damaging to individuals. If these people were directors of commercial companies they would have been jailed for negligence!

P J Browne

“He flies on private jets and is escorted in armed cars with security always close by.” This is regular behaviour for crime bosses.

What a good article. How on earth has he managed to schmooze so many leaders with his track record of ruining the UK? It shows how insecure they must feel.

This loathesome individual is bent on tagging and labelling everyone on planet earth and succeeds in making this woman determined to keep off every database that it’s humanly possible to do so. If it means I’m unable to travel then so be it.

As for global health initiatives, if they spent less on trying to vaccinate everyone (which iatrogenic harms probably cause much of the illness in the world) and more on supplying clean water and basic sanitation then they might conceivably be of some use to mankind.

What a good article. How on earth has he managed to schmooze so many leaders with his track record of ruining the UK? It shows how insecure they must feel.

This loathesome individual is bent on tagging and labelling everyone on planet earth and succeeds in making this woman determined to keep off every database that it’s humanly possible to do so. If it means I’m unable to travel then so be it.

As for global health initiatives, if they spent less on trying to vaccinate everyone (which iatrogenic harms probably cause much of the illness in the world) and more on supplying clean water and basic sanitation then they might conceivably be of some use to mankind.

They are Machiavellian, narcissistic, psychopaths with a Jesus Complex.

…and because they – the Blairs, Schwabs, Soroses and Gates of this world – do in fact wield immense power and influence they are extremely dangerous. A danger which is underestimated at our peril.

Their shared agenda is global and is in agreement with WHO and UN goals. Currently we see Blair influencing Starmer, he was in and out of No.10 during the pandemic, no doubt selling the ‘need’ for vaccine passports – which are an essential ingredient of digital governance, Blair’s prize goal. With the coming of a cashless banking system and biometric information passports a Chinese style social credit system with be imposed and all pretence of democracy finally swept away.

Hope i’m mistaken but the signs as to the destination we are hurtling towards couldn’t be clearer.

Let us not be TOO cruel but for an accident of birth the wretched Blair creature would have been a superlative Tory Wet, alongside the likes of Howe, Hesseltine, Portillo, Clarke, Cameron, May, and last but NOT least Johnson.

Not an accident of birth but an accident of marriage.

Not an accident of birth but an accident of marriage.

So what is wrong with this agenda? I want to agree but not entirely sure why. Got to resolve!!! Ukraine – Russia conflict first.

Let us not be TOO cruel but for an accident of birth the wretched Blair creature would have been a superlative Tory Wet, alongside the likes of Howe, Hesseltine, Portillo, Clarke, Cameron, May, and last but NOT least Johnson.

So what is wrong with this agenda? I want to agree but not entirely sure why. Got to resolve!!! Ukraine – Russia conflict first.

…and because they – the Blairs, Schwabs, Soroses and Gates of this world – do in fact wield immense power and influence they are extremely dangerous. A danger which is underestimated at our peril.

Their shared agenda is global and is in agreement with WHO and UN goals. Currently we see Blair influencing Starmer, he was in and out of No.10 during the pandemic, no doubt selling the ‘need’ for vaccine passports – which are an essential ingredient of digital governance, Blair’s prize goal. With the coming of a cashless banking system and biometric information passports a Chinese style social credit system with be imposed and all pretence of democracy finally swept away.

Hope i’m mistaken but the signs as to the destination we are hurtling towards couldn’t be clearer.

They are Machiavellian, narcissistic, psychopaths with a Jesus Complex.

It’s tragic really. He really thinks he can rescue his legacy by doing what he did to destroy it in the first place.

In the interests of ‘fair play’, Blair’s most egregious crime, the Iraq War needed the votes of over 140*wretched Tory MPs to cross the line.

(* I have the names recorded for future reference.)

In the interests of ‘fair play’, Blair’s most egregious crime, the Iraq War needed the votes of over 140*wretched Tory MPs to cross the line.

(* I have the names recorded for future reference.)

It’s tragic really. He really thinks he can rescue his legacy by doing what he did to destroy it in the first place.

I should be astonished that the Bungler of Baghdad, who invaded Iraq without a post victory plan leading to rise of IS etc can be taken seriously as an implementor of policy. It is disturbing that I am actually not suprprised. Money and connections are much more influential than ability.

I should be astonished that the Bungler of Baghdad, who invaded Iraq without a post victory plan leading to rise of IS etc can be taken seriously as an implementor of policy. It is disturbing that I am actually not suprprised. Money and connections are much more influential than ability.

Great job team. Britain’s WEF, bought to you from the man who hopes to succeed Schwab. The rising kleptocracy is one to watch over the next 10 years. Geopolitical hehemonic tensions, sovereign debt crisis, generative AI applications, ageing demographcs, and soi-disant climate change, mean major changes lie ahead. These organisations are, indeed, poising themselves for a reset.

Great job team. Britain’s WEF, bought to you from the man who hopes to succeed Schwab. The rising kleptocracy is one to watch over the next 10 years. Geopolitical hehemonic tensions, sovereign debt crisis, generative AI applications, ageing demographcs, and soi-disant climate change, mean major changes lie ahead. These organisations are, indeed, poising themselves for a reset.

Committed UK to War against Iraq without a mandate on the basis of lies about weapons of mass destruction. b*****d! His massive wealth isolates him from the consequences of his disastrous worldview.

Not sure it was thougt to be a ‘lies’ at the time. Hindsight is a wonderful thing!!

It was a load of hyped up twaddle, badged as ‘intelligence’ to serve a pre-set agenda. In any case, a few outdated Scud missiles with alleged chemical warheads, ‘WMD’? As a sovereign nation, Iraq had a perfect right to nuclear weaponry, let alone that sort of crude 1940s-era independent deterrent. Israel, the USSA, Pakistan, India and France were all well known to have nuclear missiles that could ‘hit Cyprus within 30 minutes’: yet that wasn’t treated as an excuse for the UK to invade them.

It was a load of hyped up twaddle, badged as ‘intelligence’ to serve a pre-set agenda. In any case, a few outdated Scud missiles with alleged chemical warheads, ‘WMD’? As a sovereign nation, Iraq had a perfect right to nuclear weaponry, let alone that sort of crude 1940s-era independent deterrent. Israel, the USSA, Pakistan, India and France were all well known to have nuclear missiles that could ‘hit Cyprus within 30 minutes’: yet that wasn’t treated as an excuse for the UK to invade them.

Not sure it was thougt to be a ‘lies’ at the time. Hindsight is a wonderful thing!!

Committed UK to War against Iraq without a mandate on the basis of lies about weapons of mass destruction. b*****d! His massive wealth isolates him from the consequences of his disastrous worldview.

I thank the author for updating me on what Mr Blair has been up to. I actually voted for him back in the 90s, as many did, believing he would rid us of what the ‘evil, greedy Tories’ were doing at the time. I used to like his energy and zeal, and what for a while appeared to be a gift for plain speaking.

But then came the lies and deception of 9/11 and the Iraq War; his anti-democratic meddling in Brexit; and most recently, his garish labelling of those Britons who chose not to take the Covid jab, as “idiots”.

Given what has been unfolding from this sinister health debacle, his advice and opinion must now be considered dangerous, ill-informed, and possibly even suspect.

I feel the sooner he withdraws from advising the British government, the better. People with his views cannot be trusted.

Perhaps you would like to shoot him?

Rather like you thought that Ms Ashli BABBIT deserved to be SHOT?

What a daft thing to say. Rather betrays your mode of thinking I suspect.

What a daft thing to say. Rather betrays your mode of thinking I suspect.

Perhaps you would like to shoot him?

Rather like you thought that Ms Ashli BABBIT deserved to be SHOT?

I thank the author for updating me on what Mr Blair has been up to. I actually voted for him back in the 90s, as many did, believing he would rid us of what the ‘evil, greedy Tories’ were doing at the time. I used to like his energy and zeal, and what for a while appeared to be a gift for plain speaking.

But then came the lies and deception of 9/11 and the Iraq War; his anti-democratic meddling in Brexit; and most recently, his garish labelling of those Britons who chose not to take the Covid jab, as “idiots”.

Given what has been unfolding from this sinister health debacle, his advice and opinion must now be considered dangerous, ill-informed, and possibly even suspect.

I feel the sooner he withdraws from advising the British government, the better. People with his views cannot be trusted.

I voted for the b*****d 3 Times. Mea Maxima Culpa.

You should be ashamed of voting Labour, never mind Blair.

That’s a bit harsh. That comment from a true blue Conservative who feels disenfranchised.

That’s a bit harsh. That comment from a true blue Conservative who feels disenfranchised.

I think 1997 was excusable – it was “time for a change”. No free pass on the next two I’m afraid.

You should be ashamed of voting Labour, never mind Blair.

I think 1997 was excusable – it was “time for a change”. No free pass on the next two I’m afraid.

I voted for the b*****d 3 Times. Mea Maxima Culpa.

For my sins I used to work on immigration for a small campaigning body, ‘helped’ by a ‘partnering’ org funded by Blair and Soros.

A lot of the job was keeping them out of our meetings . . . on our issues.

Because it emerged that they didn’t have any issue of their own, well none so much as a permanent need for attention.

For my sins I used to work on immigration for a small campaigning body, ‘helped’ by a ‘partnering’ org funded by Blair and Soros.

A lot of the job was keeping them out of our meetings . . . on our issues.

Because it emerged that they didn’t have any issue of their own, well none so much as a permanent need for attention.

He’s shallow. I don’t subscribe to the idea of him as some nefarious Great Reset agent, he’s just superficial.

Look at everything he did while PM; fatuous and damaging Constitutional changes, screwing up further education, clueless on the economy to the point he delegated that to Brown and headed off to International Politics as fast as he could.

He’d be deeply at home in a large Corporation redirecting it from the messy business of beating competitors and serving customers and focussing on ESG.

I’ll give him one thing, he’s quite possibly the Worlds leading schmoozer.

He’s shallow. I don’t subscribe to the idea of him as some nefarious Great Reset agent, he’s just superficial.

Look at everything he did while PM; fatuous and damaging Constitutional changes, screwing up further education, clueless on the economy to the point he delegated that to Brown and headed off to International Politics as fast as he could.

He’d be deeply at home in a large Corporation redirecting it from the messy business of beating competitors and serving customers and focussing on ESG.

I’ll give him one thing, he’s quite possibly the Worlds leading schmoozer.

His innocence?

His immortal soul.

His innocence?

His immortal soul.

The new face of global socialism!

I assume you’re being sarcastic, but, in reality, as you well know, and primarily for the benefit of e.g. any American readers who may be more inclined to take your comment at face value, Blair is a socially-moderate Tory, who has more in common with e.g., John Major or Michael Heseltine than he does with any traditional socialist Labour person.

For instance, real British socialists detest Tony Blair, and the angry epithets and put-downs used to describe him by the British hard-left are (ironically) very reminiscent to those that a typical Unherd reader would use to describe him:

https://socialist.net/blairism-a-legacy-that-must-be-buried/

Even as far back in 1996, his essential conservatism was noted:

“And Blair agrees with her. He is the first of the Tories’ political opponents ever to concede that they have largely won the argument. An anthology of Blair’s recent reflections speaks for itself.

“I believe Margaret Thatcher’s emphasis on enterprise was right.”

“A strong society should not be confused with a strong state.”

“Duty is the cornerstone of a decent society.”

“Britain needs more successful people who can become rich by success through the money they earn.”

“People don’t want an overbearing state.”

Someone who knows him says, “You have to remember that the great passion in Tony’s life is his hatred of the Labour Party.”

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1996/06/the-paradoxical-case-of-tony-blair/376602/

For the benefit of any Americans viewing, Blair is not a socially moderate anything. He is, and always was, a charlatan. Gordon Brown, a flawed individual admittedly, clearly saw through him.

And we all saw through Broon.

And we all saw through Broon.

This is true. His focus was on the aspirations of individuals. He wasn’t a big-state guy.

The labor unions didn’t like him because he believed that they glorified “working class” status. He understood that most people were acquisitive and aspired to improve financially.

For the benefit of any Americans viewing, Blair is not a socially moderate anything. He is, and always was, a charlatan. Gordon Brown, a flawed individual admittedly, clearly saw through him.

This is true. His focus was on the aspirations of individuals. He wasn’t a big-state guy.

The labor unions didn’t like him because he believed that they glorified “working class” status. He understood that most people were acquisitive and aspired to improve financially.

I assume you’re being sarcastic, but, in reality, as you well know, and primarily for the benefit of e.g. any American readers who may be more inclined to take your comment at face value, Blair is a socially-moderate Tory, who has more in common with e.g., John Major or Michael Heseltine than he does with any traditional socialist Labour person.

For instance, real British socialists detest Tony Blair, and the angry epithets and put-downs used to describe him by the British hard-left are (ironically) very reminiscent to those that a typical Unherd reader would use to describe him:

https://socialist.net/blairism-a-legacy-that-must-be-buried/

Even as far back in 1996, his essential conservatism was noted:

“And Blair agrees with her. He is the first of the Tories’ political opponents ever to concede that they have largely won the argument. An anthology of Blair’s recent reflections speaks for itself.

“I believe Margaret Thatcher’s emphasis on enterprise was right.”

“A strong society should not be confused with a strong state.”

“Duty is the cornerstone of a decent society.”

“Britain needs more successful people who can become rich by success through the money they earn.”

“People don’t want an overbearing state.”

Someone who knows him says, “You have to remember that the great passion in Tony’s life is his hatred of the Labour Party.”

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1996/06/the-paradoxical-case-of-tony-blair/376602/

The new face of global socialism!

Treacherous betrayer of Britain, ruination of the nation, now he brings his destruction to the world. It would be better if we had imprisoned him as would have been just.

Treacherous betrayer of Britain, ruination of the nation, now he brings his destruction to the world. It would be better if we had imprisoned him as would have been just.

Global change? To what? Stability in the Middle East? A home for the refugees to return to? An end to the Ukraine confrontation? Rebuilding Ukraine? Curtailing eastern fossil fuel use, if it is in fact even necessary?

Blair still has blood on his hands and no obvious philanthropy to wash it away. His influence is yet to trickle down to 23 Acacia Avenue; or Karachi.

His ilk, the Clintons, Obamas, Trudeaus, Bidens, Arderns, the Oz Labor Party, Scholz, Macron, Rutte must be a severe disappointment to him. They’ll be ousted soon. Leaving him where? The UK Labour Party and their two dimensional mannequin leader?

Global change? To what? Stability in the Middle East? A home for the refugees to return to? An end to the Ukraine confrontation? Rebuilding Ukraine? Curtailing eastern fossil fuel use, if it is in fact even necessary?

Blair still has blood on his hands and no obvious philanthropy to wash it away. His influence is yet to trickle down to 23 Acacia Avenue; or Karachi.

His ilk, the Clintons, Obamas, Trudeaus, Bidens, Arderns, the Oz Labor Party, Scholz, Macron, Rutte must be a severe disappointment to him. They’ll be ousted soon. Leaving him where? The UK Labour Party and their two dimensional mannequin leader?

Having read this excellent article one can only appreciate even more why Brexit happened? The sheer conceit of Blair to airbrush the Iraq invasion, David Kelly’s suicide(or murder?) for revealed the WMD lies, the secret plan for mass migration from the EU, the 2008 UK Banking Crash and the immoral home confinements and vaccine mandates out of his past is incredible.

November 1997 Tony Blair “”I think most people who have dealt with me think I am a pretty straight sort of guy, and I am,”

Sadly, so many are still taken in by the fakery!

Having read this excellent article one can only appreciate even more why Brexit happened? The sheer conceit of Blair to airbrush the Iraq invasion, David Kelly’s suicide(or murder?) for revealed the WMD lies, the secret plan for mass migration from the EU, the 2008 UK Banking Crash and the immoral home confinements and vaccine mandates out of his past is incredible.

November 1997 Tony Blair “”I think most people who have dealt with me think I am a pretty straight sort of guy, and I am,”

Sadly, so many are still taken in by the fakery!

As a student in the 1990s I was extremely disappointed in Blair. I was never really into politics, but back then many of us believed that Labour being voted in would reverse the trend of growing inequality in Britain. Blair radically transformed Labour from a working class party to a middle-class party. After a few months it was very clear he was more concerned with how he came across and joining the ranks of the rich than actually doing anything useful for the working poor.

As a student in the 1990s I was extremely disappointed in Blair. I was never really into politics, but back then many of us believed that Labour being voted in would reverse the trend of growing inequality in Britain. Blair radically transformed Labour from a working class party to a middle-class party. After a few months it was very clear he was more concerned with how he came across and joining the ranks of the rich than actually doing anything useful for the working poor.

Really great article – thank you. Full of very interesting information – and even a reference to Goodbye, Lenin…a favourite of mine since I saw it in the cinema in Munich back in 2003.

The bits which particularly leapt out at me were the paragraphs about Blair’s tendency towards going for things he has faith in. I read “My Journey” while on holiday in 2012 and I do recall becoming quite uncomfortable about how closely Blair’s religious faith was tangled up in big political decisions such as Iraq.

While political decisions are never purely rational and have elements of emotion, power-play, moral values and ethics all bound up in them – I think it was the way Blair was so up front about his (religious) faith that made me start seriously questioning his leadership.

Reading this, it appears that this Blairite “faith” isn’t just of a religious bent, but extends to ideas or technological development. This enthusiasm comes across as being a bit childlike in nature. He has a sort of “faith in faith”.

And that’s all lovely for him on a personal level, but when faith comes into contact with big politics, it means that big decisions are being made on the back of something quite intangible, non-transparent and inexplicable…which, unsurprisingly, fails to inspire “faith” in the people who have seen where Blair’s decisions got us previously.

I’m sure that other leaders are guided by their faith too, but the trick is to keep quiet about it. Blair seems to think that he’s some kind of messiah and that talk of faith is a part of the role he has been sent to play.

Really great article – thank you. Full of very interesting information – and even a reference to Goodbye, Lenin…a favourite of mine since I saw it in the cinema in Munich back in 2003.

The bits which particularly leapt out at me were the paragraphs about Blair’s tendency towards going for things he has faith in. I read “My Journey” while on holiday in 2012 and I do recall becoming quite uncomfortable about how closely Blair’s religious faith was tangled up in big political decisions such as Iraq.

While political decisions are never purely rational and have elements of emotion, power-play, moral values and ethics all bound up in them – I think it was the way Blair was so up front about his (religious) faith that made me start seriously questioning his leadership.

Reading this, it appears that this Blairite “faith” isn’t just of a religious bent, but extends to ideas or technological development. This enthusiasm comes across as being a bit childlike in nature. He has a sort of “faith in faith”.

And that’s all lovely for him on a personal level, but when faith comes into contact with big politics, it means that big decisions are being made on the back of something quite intangible, non-transparent and inexplicable…which, unsurprisingly, fails to inspire “faith” in the people who have seen where Blair’s decisions got us previously.

I’m sure that other leaders are guided by their faith too, but the trick is to keep quiet about it. Blair seems to think that he’s some kind of messiah and that talk of faith is a part of the role he has been sent to play.

He should be in prison.

My conscious is clear, I never voted for him.

He should be in prison.

My conscious is clear, I never voted for him.

Getting to grips with democracy one private jet at a time.

See also Bill Gates. Although that’s more solving the climate crisis, one PJ at a time. (Apparently he has four.)

See also Bill Gates. Although that’s more solving the climate crisis, one PJ at a time. (Apparently he has four.)

Getting to grips with democracy one private jet at a time.

I admit, to my eternal shame, that in 1997 I voted for this charlatan.

Don’t worry, we all make mistakes.

I seem to recall millions of the ‘master race’ saying the same thing about Adolph!

As with all politicians, past and present, opinions on Blair vary. However, your comment is not only unjustified, but grossly inadequate.

Could you expand on that please?

As at 12.15 BST you have had two hours to explain yourself? What’s the problem?

Could you expand on that please?

As at 12.15 BST you have had two hours to explain yourself? What’s the problem?

As with all politicians, past and present, opinions on Blair vary. However, your comment is not only unjustified, but grossly inadequate.

At least shows you were right once PR. Hold onto that.

I did in 2001 and 2005 so I’ll dive right into that pool of eternal shame with you.

Don’t worry, we all make mistakes.

I seem to recall millions of the ‘master race’ saying the same thing about Adolph!

At least shows you were right once PR. Hold onto that.

I did in 2001 and 2005 so I’ll dive right into that pool of eternal shame with you.

I admit, to my eternal shame, that in 1997 I voted for this charlatan.

‘But how much of this is actually real? “Do governments really want his strategic advice,” one person who knows Blair put it to me, “or his phone number?”’

So, the obvious question is – what benefit does Tony actually offer? Why do all these VIPs meet him, and give him money?

The obvious suspicion, weirdly not raised in this article, is the TBI acts as a conduit for corporate / “philanthropic” bribes to government officials and relevant “delivery” leaders to adopt the TBI’s clients’ agendas.

The obvious suspicion, weirdly not raised in this article, is the TBI acts as a conduit for corporate / “philanthropic” bribes to government officials and relevant “delivery” leaders to adopt the TBI’s clients’ agendas.

‘But how much of this is actually real? “Do governments really want his strategic advice,” one person who knows Blair put it to me, “or his phone number?”’

So, the obvious question is – what benefit does Tony actually offer? Why do all these VIPs meet him, and give him money?

Just read an op ed in the Spectator World about Barack Obama’s third term as shadow government in the Biden White House. How these people live in a completely different world but yet exert such influence on ours is truly terrifying.

Just read an op ed in the Spectator World about Barack Obama’s third term as shadow government in the Biden White House. How these people live in a completely different world but yet exert such influence on ours is truly terrifying.

Power without responsibility…

Power without accountability, more like.

Power without accountability, more like.

Power without responsibility…

Pretty good investigation, more like this please!

Pretty good investigation, more like this please!

In a nutshell, he still thinks he’s the messiah.

In a nutshell, he still thinks he’s the messiah.

Their Terrifying Plan written by Vernon Coleman. Sums what is happening in the world by powerful rich people determined to change how we hoi polloi will live in the future.

Their Terrifying Plan written by Vernon Coleman. Sums what is happening in the world by powerful rich people determined to change how we hoi polloi will live in the future.

Bush offered him a place at the top table – money, unaccountable power,etc – for backing him on Iraq. That he was fully prepared to lie to parliament, the country – even himself perhaps? –

shows why no one should trust such a messianic maniac. His hubris and hunger caused hundreds and thousands of deaths.

Bush offered him a place at the top table – money, unaccountable power,etc – for backing him on Iraq. That he was fully prepared to lie to parliament, the country – even himself perhaps? –

shows why no one should trust such a messianic maniac. His hubris and hunger caused hundreds and thousands of deaths.

I can see how Blair and his technocrats might be considered an answer to populism, but in another sense he seems rather like a populist: someone riding his “fatalism” regarding globalization and technology, rather than pining away for values of individualism and the natural. In short, an opportunist. As an American, I recall how attractive Blair seemed to many of us that supported Clinton–a liar, but our liar–when Clinton’s bad boy behavior proved so vulgar so quickly. This fine article helps this American realize that saviors with ID cards are everywhere to be feared.

I can see how Blair and his technocrats might be considered an answer to populism, but in another sense he seems rather like a populist: someone riding his “fatalism” regarding globalization and technology, rather than pining away for values of individualism and the natural. In short, an opportunist. As an American, I recall how attractive Blair seemed to many of us that supported Clinton–a liar, but our liar–when Clinton’s bad boy behavior proved so vulgar so quickly. This fine article helps this American realize that saviors with ID cards are everywhere to be feared.

An excellent article, well researched and very sinister. Blair has used exactly the same methods as the WEF to expand his influence, placing people at the heart of the governments and administrations where he wants to exert it.

“and even forming an alliance where necessary to defeat their existential enemy: the “populists” who must never be appeased. I was told Blair was firmly in the latter camp”

The irony of this is that Blair himself was the first truly populist leader in modern times after a certain Austrian gentleman in the 1930s, and using many of the same methods like controlling the media via the Murdoch press and, of course, the BBC.

Talking of “methods”, a true anecdote from 1996. Years ago I was very friendly with a woman whose husband ran one of the PR companies that New Labour used. The central Blair cabal would hold meetings at her home, well away from prying ears and eyes. She herself was a life-long Labour supporter. Gradually she started drinking and eventually became an alcoholic. She told me that she heard things at those meetings that frightened the life out of her – literally – she said that if she ever repeated them her life would be in danger. Even in her most drunken moments she never revealed anything to me, just bursting into tears if I tried to probe. Her marriage did not last and I lost touch with her many years ago due largely to her alcoholism – she would phone me at all hours of the night babbling on incoherently – so I do not know what happened to her. She was a highly intelligent woman, and I wouldn’t have said a weak one either, but her life was ruined by what she learned from that association.

An excellent article, well researched and very sinister. Blair has used exactly the same methods as the WEF to expand his influence, placing people at the heart of the governments and administrations where he wants to exert it.

“and even forming an alliance where necessary to defeat their existential enemy: the “populists” who must never be appeased. I was told Blair was firmly in the latter camp”

The irony of this is that Blair himself was the first truly populist leader in modern times after a certain Austrian gentleman in the 1930s, and using many of the same methods like controlling the media via the Murdoch press and, of course, the BBC.

Talking of “methods”, a true anecdote from 1996. Years ago I was very friendly with a woman whose husband ran one of the PR companies that New Labour used. The central Blair cabal would hold meetings at her home, well away from prying ears and eyes. She herself was a life-long Labour supporter. Gradually she started drinking and eventually became an alcoholic. She told me that she heard things at those meetings that frightened the life out of her – literally – she said that if she ever repeated them her life would be in danger. Even in her most drunken moments she never revealed anything to me, just bursting into tears if I tried to probe. Her marriage did not last and I lost touch with her many years ago due largely to her alcoholism – she would phone me at all hours of the night babbling on incoherently – so I do not know what happened to her. She was a highly intelligent woman, and I wouldn’t have said a weak one either, but her life was ruined by what she learned from that association.

Don’t you just know that not a cent of the vast sums of money that the TBI sucks in is paid by anyone from their own pocket: it’s all other peoples’ money.

Don’t you just know that not a cent of the vast sums of money that the TBI sucks in is paid by anyone from their own pocket: it’s all other peoples’ money.

“I am a sprinter,” Ellison once remarked. “I rest, I sprint, I rest, I sprint again.”

Jesus wept….

“I am a sprinter,” Ellison once remarked. “I rest, I sprint, I rest, I sprint again.”

Jesus wept….

Thanks for an enthralling article which made my head spin as I tried to connect all the dots, organisations, governments and people. I kept being reminded of Tom Lehrer’s classic lines:

“Evr’y evening you will find him

Around our neighbourhood

It’s The Old Dope Peddler

Doing well by doing good”.

Tony has been doing well by doing good, at least in his own eyes. I loved his pal Larry Ellison’s island project combining a luxury resort with agricultural research.

Practically all the consultancy work in Africa looks like the dictionary definition of “white saviour” initiatives, helping the benighted natives to achieve what they are too stupid or ignorant or corrupt to achieve unaided. Any independent evaluation of all this consultancy money and effort? I guess you would need another bunch of eye poppingly expensive White Saviours to judge what the first lot achieved.

To be fair to Tony, at least he is not lecturing us on climate change while globetrotting on his private jets. And all those armoured cars must burn more gas than your average family hatchback.

Having done some accountancy training, I know that there’s more to financial reports than boring arithmetic can describe. But Larry alone apparently “committed” 83.2 million bucks to the TBI in 2021 when its turnover was 81 million. As Tony’s fellow lawyer pal Bill Clinton would probably say, it all depends what you mean by “committed” and “83” and “turnover”……

Good point about Blair NOT haranguing us about Climate Hysteria!

Perhaps “every cloud has………”

good point about “creative” accounting . As an accomplished bullshit artist we can assume Blair is bullshitting about his financial power and number of staff…800 !

Good point about Blair NOT haranguing us about Climate Hysteria!

Perhaps “every cloud has………”

good point about “creative” accounting . As an accomplished bullshit artist we can assume Blair is bullshitting about his financial power and number of staff…800 !

Thanks for an enthralling article which made my head spin as I tried to connect all the dots, organisations, governments and people. I kept being reminded of Tom Lehrer’s classic lines:

“Evr’y evening you will find him

Around our neighbourhood

It’s The Old Dope Peddler

Doing well by doing good”.

Tony has been doing well by doing good, at least in his own eyes. I loved his pal Larry Ellison’s island project combining a luxury resort with agricultural research.

Practically all the consultancy work in Africa looks like the dictionary definition of “white saviour” initiatives, helping the benighted natives to achieve what they are too stupid or ignorant or corrupt to achieve unaided. Any independent evaluation of all this consultancy money and effort? I guess you would need another bunch of eye poppingly expensive White Saviours to judge what the first lot achieved.

To be fair to Tony, at least he is not lecturing us on climate change while globetrotting on his private jets. And all those armoured cars must burn more gas than your average family hatchback.

Having done some accountancy training, I know that there’s more to financial reports than boring arithmetic can describe. But Larry alone apparently “committed” 83.2 million bucks to the TBI in 2021 when its turnover was 81 million. As Tony’s fellow lawyer pal Bill Clinton would probably say, it all depends what you mean by “committed” and “83” and “turnover”……

Reads like a plot for a scary movie.

Reads like a plot for a scary movie.

Sounds like Meghan Markle with a much larger staff.

Sounds like Meghan Markle with a much larger staff.

The Wagner Group of the extreme centre.

The Wagner Group of the extreme centre.

Great work by Tom as always.

What I find interesting is the maximisation of the trend that politicians move away from being drivers of change to merely implements of change.

In a previous age it was not uncommon to see those who wanted to effect change go and get elected. I was genuinely humbled to hear from (now retired) MPs about their sense of duty to help generate positive change.

But first in the US and inevitably in the UK, it has proven much cheaper and more efficient to remain in the private sector and outsource an agenda via funding private offices & think tanks. Tom’s article outlines how the TBI is worthy of a Harvard Business School case study on just such a transition.

Great work by Tom as always.

What I find interesting is the maximisation of the trend that politicians move away from being drivers of change to merely implements of change.