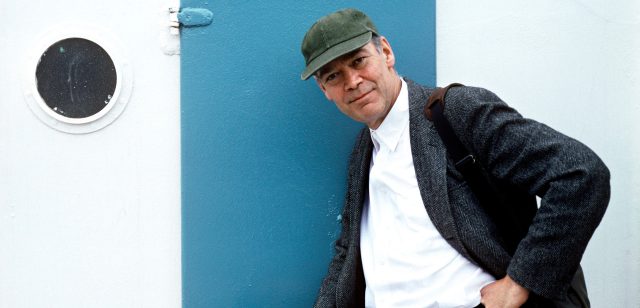

“He was my first reader” Ulf Andersen/Getty Images

A week or so before he died, Jonathan Raban sent me an email:

“I apologise for my dreadful tardiness in reading your manuscript, and promise you an explanation later. Many thanks for your communiques from the ship, and you are a better man than I. Love, J and Happy New Year.”

I happened to be sailing in the Indian Ocean: Raban, a now land-locked sailor, delighted in hearing of the sort of seas and weather and coastlines he extolled in Coasting and Passage to Juneau. A few days later, his explanation came in a message to his closest friends:

“I’m in hospital, so drugged up that I cannot physically write and am dictating this to Julia… I may be back in perhaps a month’s time or I may not be back during my lifetime… I’m sorry not to be able to write to you individually but I need you to know how ‘iffy’ my health and likelihood of much further life are.”

He went on to describe in detail his serious medical condition, then closed: “This is not a subtle letter. But I hope it answers to the immediate moment.”

This was characteristic Jonathan: fluent, responsive, uncomplaining, clear-sighted, fatalistic. What he called his “dreadful tardiness” in reading my manuscript was only a few weeks. He was my first reader. I sent him my final drafts and he always responded with a long message within a few days — no editor I have ever had, in almost 60 years, has been this prompt with a manuscript, which is obviously why I depended on Jonathan. He did the same with me, over the years, sending me his work in progress, asking for a response.

It is cold comfort but still a satisfaction to know that just a month or so ago he did the final edits on a book he’d been working on for 10 years or more, a memoir recounting his stroke in 2011, his war-time childhood, and his father’s role as an officer in European and Middle Eastern battles; his most ambitious book, a complex story conflating personal history with national history, illness, loyalty and conflict. It was not until he got to the end that he found the title. A few months ago, he wrote me: “Book has title now: ‘Father and Son,’ my suggestion, and a steal from Edmund Gosse, an agnostic whose father was a Plymouth Brethren preacher… Two clergymen, two sons.”

I was teaching Shakespeare’s Contemporaries at the University of Singapore when, in 1969, out of the blue he sent me a letter. He had just reviewed two of my novels, Girls at Play and Murder in Mount Holly, and found them to his taste. His enthusiasm was very Jonathan: whenever he found a book he liked he formed a friendship with the writer. It had started when he was a student in Hull with Philip Larkin, and later he drew Angus Wilson into his orbit, and Robert Lowell, Ian Hamilton, and others, including me when I moved to London. I remember one evening in the Seventies we were to meet at The Savile Club to play snooker and he said: “I’d like you to meet a short story writer — very young but wonderful, from East Anglia, Ian McEwan.”

Defining what we did for a living, he once said in an interview: “The term ‘man of letters’ now seems hopelessly archaic, but I’d like to think there’s still life left in the notion of the writer who’s just a writer, someone who shifts from form to form, unselfconsciously, as so many of the Victorians did, without the critical police telling them they were trespassing across professional boundaries.”

Like many enthusiasts, he needed his enthusiasm to be answered; as an encourager and a supporter, he expected encouragement and support. He knew that writers needed to be boosted, that all of us looked for affirmation from writers we respect. Jonathan wrote so well on so many different topics he was easy to praise. He was an exacting, often withering critic, and yet one of the thinnest-skinned writers I have ever known. After receiving a negative review he drooped and took to his bed, wounded and wordless.

Early on, he saw himself as a Londoner, but untethered — “Temporary People” was to be the title of a proposed book about Londoners. He was buoyed by the energy of the city, but talked constantly about George Gissing and thought of writing an updated version of New Grub Street but wrote Soft City instead, a celebration of the transformative forces emerging in early-Seventies London.

He was then living in a flat owned by Robert Lowell and Lady Caroline Blackwood, and saw himself with a future as a London dramatist. He wrote a number of radio plays. He regarded playwriting as a great career; the revenues, he laughed, “an annuity!” After I came back from my long, difficult trip through Asia that became The Great Railway Bazaar — and I’d returned to a fractured marriage — he told me with utter certainty: “I hate travel. The only exception I’d make would be to take the boat to Ireland to go fishing.”

He then wrote a TV play titled Snooker, based on a writer who returns from his travels to a fractured marriage — nudge, nudge. And later, returning the favour, I wrote a long story called Lady Max, with a recognisable Lady Caroline and a scarcely disguised Jonathan as a seedy Londoner named Ian Musprat.

His stage play The Sunset Touch premiered at the Bristol Old Vic in 1977 and was panned by critics. Jonathan became mute and took to his bed, but was chivvied by the Radio Times for an assignment to write about a TV show: Dame Freya Stark on the Euphrates in Iraq. It was an epiphany. He returned bewitched, having discovered the freedom and enlightenment in travel, its usefulness to a writer stumped for an idea, new landscapes, new people, bizarre meals, funny voices; it meant material, and money. He soon set off, not for Ireland but for the Middle East and returned with enough material for Arabia Through the Looking Glass, Jonathan as Alice among the Arabs.

He abandoned playwriting and sailed down the Mississippi in a small boat, a trip that resulted in Old Glory, and the following year decided to sail around Britain, but in a bigger boat. At the same time, wishing to see more of Britain, I had the idea of walking and riding around the British coast. It was a perfect time, the spring of 1982, Thatcher in charge and the Falklands War producing serious casualties. I was walking clockwise from Margate, he was sailing the other way round; we met in Brighton, and ultimately wrote about each other, Jonathan describing me in Coasting, my portrait of him appearing in The Kingdom by the Sea.

He never ceased to be a trenchant critic, but travel proved a cure for his restlessness and gave him a new career. And he fell in love once more, with a woman from Seattle, and married for a third time, a union that didn’t last long but produced a daughter, Julia, who gave him more joy and love than he’d ever imagined. I’ve rarely seen a more doting dad, and it was a plus that Julia turned out to be highly intelligent, a Stanford graduate and a devoted child who gave him companionship and care in his later years.

He lived in Seattle, still a British citizen for 33 years, and never lost his faintly plummy accent or his evaluating alien eye. He wrote about places Americans tended to ignore: the bleak plains of Montana, the choppy seas of the Alaskan inland passage — more books. America, susceptible to plummy-accented satirists, is hospitable to the English, who fancy the elbow room, the attention, and I guess the money.

Jonathan was squeamish about the term travel writer, because of course Dudley Pismire, who just returned from a sojourn in Benidorm to write on paella for the Bradford Bugle, also calls himself a travel writer. And Raban wasn’t the only one who squirmed — Chatwin and Sebald and others objected to being called travel writers, feeling they were creating a superior form. Chatwin called his Songlines fiction, but is it anything more, like Jonathan’s, than punched-up and at times florid and better-educated travel writing? In most respects it is no different — personal and satirical and moralising — than Trollope’s The West Indies and the Spanish Main. In his way, Thoreau’s A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers is equally modern — a very long book about a very short trip, filled with philosophical musings, afterthoughts and rubious generalities. I speak as a sometime travel writer.

For years our friendship was epistolary, though I occasionally visited him in Seattle. The last time I paid Jonathan a visit was in 2019. He was much thinner, in a wheelchair — “I’m a housebound crip.” He’d lost the use of one arm, and a few years later one leg was amputated; his hearing was poor, he’d lost all his hair, and when I remarked that he was banged up and whittled away like Lemuel Pitkin in Nathanael West’s A Cool Million, he laughed.

Being sedentary is the natural condition of a writer, and he made the most of it with the latest technology, voice-recognition software and computer programs. He was at this point about halfway through his book, and he was smoking a cigar as we talked of old times, fishing in Appleby with Cal Lowell, lunching with Angus and Ian in London, walking the Thames footpath from Putney to Kingston, writing reviews for the New Statesman — two old coots recalling pitiful advances and rivalries, the joys of a precarious existence as residents of Grub Street.

Jonathan was always the first person I hastened to with an idea, or a story, to have a good grouse with, to share a joke, or to ask for advice. I feel diminished by his death. There’s no one else now. Such friends are irreplaceable.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe