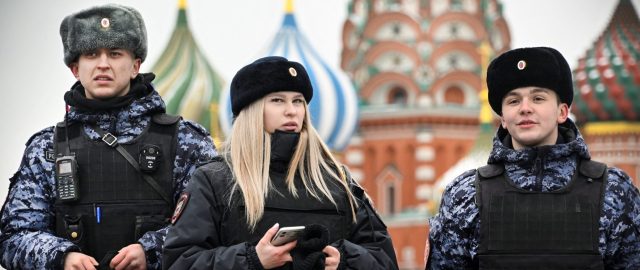

Victims or villains? Alexander Nemenov/AFP/ Getty Images

If you were a Russian mother, would you rather believe that your son gave his life heroically fighting Ukrainian Nazis, or that he died butchering innocent civilians? The former, most likely. It is not easy to admit — to oneself or to others — that you live in a country that has murdered tens of thousands of Ukrainians, or that has pointlessly sacrificed the lives of its own people.

Yet it is one thing to turn a blind eye to the truth, and quite another to be “brainwashed”. The West is fixated on the idea that “Putin’s war” is not Russia’s, and that the Russian people only support it because they have been “zombified” by a totalitarian regime. But this is missing the wood for the trees.

Independent polling claims that 75% of Russians approve of the war, a figure that has been relatively stable since March 2022 — despite a slight wavering when mobilisation was introduced in September. Similarly, Putin’s current approval rating remains at 80%, some 15-20% higher than it was before the invasion. Of course, opinion polls conducted in an authoritarian country must be treated with caution: a June 2022 study by political scientists Philipp Chapkovski and Max Schuab estimated that between 10-15% of Russian respondents may have lied to pollsters about supporting the war. But that still leaves a majority in favour.

Ever since Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014, ordinary Russians have been helping Putin to weave a narrative about the invasion. In those early days, people could easily access opposition and Russian-language Western media, but most preferred to listen to — and pass on — tall tales of Ukrainian Nazis under the spell of evil Westerners.

Russian TV news channels, which have long been the most trusted form of media, especially among older audiences, latched on to this popular opinion. It would be naïve to think they could get away with anything else, given that they rely on advertising revenue for income. Even today, producers schedule shows because they’re lucrative, not just because they uphold state propaganda (although they do need to stay on the Kremlin’s good side). Such was the demand for war propaganda following Russia’s invasion — from on high and below — that some channels ran pro-war content for up to 10 hours a day. After six months, however, audiences grew tired of the constant barrage and started to switch off, hitting advertising revenues. In response, the channels replaced some of the political propaganda shows with soaps, sports and lifestyle programmes.

Russians aren’t dependent on state television for all their news. Ordinary people can still read and watch almost all alternative sources using a VPN, which one in four Russians use. Even without a VPN, the Internet is mostly free, if manipulated, and the social media app Telegram acts as an uncensored news source for some 40 million Russians. Use of Telegram has tripled since the war began but, of the top 10 political channels, nine are virulently pro-war. Clearly, these are narratives that Russians are seeking out and choosing to believe.

As a specialist in Russian propaganda, I have analysed tens of thousands of pro-war Telegram posts and media articles, identifying three main narrative groups, or themes, all upheld by the belief that Ukrainians are in fact Russians, and that Ukraine is not a real country. The first group is rooted in Second World War mythology, arguing that Russians are not fighting against Ukraine but against Nazism, which has reappeared in Ukraine as evidenced by Kyiv’s alleged “genocide of Russian speakers”. The second casts Russians as “misunderstood angels” who are liberating Ukrainians. In this, Russia appears to be aping Western justifications for their wars in the Middle East: there is the same self-satisfied denialism of claiming to bring people freedom and rights by bombing them.

The third category portrays Russia as the underdog, fighting wildly against the odds to defend itself from a Russophobic Western military machine and malign mercenaries from Nato. Combined with the impact of sanctions, this argument has even appealed to some of the more metropolitan and well-educated Russians, who now feel victimised by their government as well as by the West, and resent the latter’s support for Ukraine. For many in poorer regions, especially those bordering Ukraine, Nato’s military aid simply confirms their long-held suspicion that the West is out to destroy Russia, just as it tried to do under Hitler and before that Napoleon.

When pressed on who, apart from Putin, is responsible for the war, many intellectual elites blame the “sovok” or Homo Sovieticus of the regions, arguing that such people are Soviet-moulded yokels who will do what any leader tells them. Not entirely unlike your North London liberals who see everyone who voted for Brexit as an idiot or a racist, or your coastal elites who depict Trump voters as shills or fascists, Russian intellectual elites see their own country from on high. As the celebrated Ukrainian-born writer, Nikolai Gogol, said: “In Russia, there is great ignorance of Russia. Everyone lives in foreign journals and newspapers, rather than their own land.”

In my conversations with Westernised anti-war, middle-class Russians, they insisted they didn’t know anyone who supported the war (though pro-war Russians inhabited a similar echo-chamber, reflecting high levels of polarisation in Russian society) and spoke disparagingly of those who did. “They sold their souls to the devil, like in 1933,” said one. Another suggested: “War drags in the dregs of humanity, often people from the poorest regions, with very little education, which means they are more prone to propaganda.”

Such snobbery conceals the full picture. The popular belief in the West, and among Russia’s anti-war elite, that ordinary Russians have been zombified into supporting a war they hate is another form of propaganda altogether: one that refuses to accept that intelligent people could come to a different perspective. Rather than engaging with the complexity of how ordinary Russians come to justify or even approve terrible crimes against innocent people, some Western commentators are choosing to externalise all the blame to a single culprit, a Grey Cardinal or bad tsar.

Of course, there are Russian government organisations that work on influencing popular opinion, but they can’t trick people into believing whatever they want. Such agencies rely on pre-existing beliefs and seek to isolate events, stories, and motifs that resonate organically with people, using them to steer audiences in the desired direction. For example, Russian media and politicians frequently refer to soldiers as heirs to the heroic Red Army to galvanise support for the war. But propaganda works on different people in different ways. Those inured to, or just sceptical of, such pathos-laden propaganda, will feel ever more inclined towards apathy. And this is why it is can often make more sense to talk of Russian consent, approval, or acquiescence to the war, rather than support.

Russians — as is the case with most citizens of autocracies — are often politically disengaged and doubt their ability to understand politics. The pro-Kremlin media plays on this uncertainty with wild conspiracies demonstrating the manipulative nature of politics abroad. The Golden Billion doomsday scenario, for instance, in which powerful Western elites control world events to amass great wealth and destroy ordinary people’s lives, is endorsed by high-ranking officials, such as head of the security council, Nikolai Patrushev, a close ally of Putin. For more sophisticated viewers, the presenters may even throw in a knowing wink at the manipulative nature of politics at home as well. Such tactics feed a sense of apathy: if everyone is lying, including the West, there is no point trying to work out the truth.

The Kremlin is offering a different reality: a nicer version, in which Russians are victims, not villains, and their sons and husbands are warriors, not war criminals. It is no surprise that Russians would opt for comforting lies and twisted myths — and it is important to understand why. But we can recognise the deeply unfair and unpleasant situation that ordinary Russians face without claiming that large swathes of Russian society oppose Putin’s barbarous war on Ukraine.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe