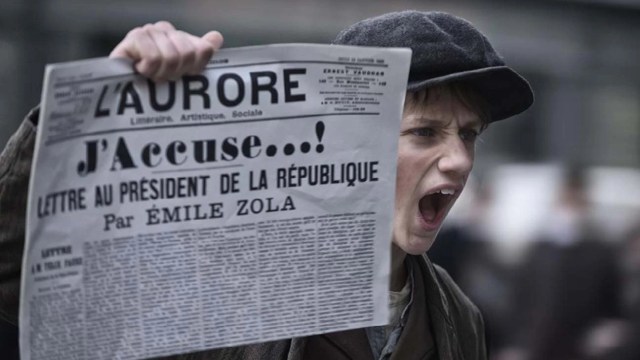

‘Truth is on the march, and nothing will stop it’ (Gaumont/ J’Accuse)

On January 13, 1898, Parisians awoke to the chorus of hundreds of news criers who, striding along the grand boulevards and brandishing copies of the newspaper L’Aurore, were shouting passages from the article that sprawled across the front page. It had originally been titled by its author, the novelist Émile Zola, “A Letter to M. Félix Faure, President of the Republique”. But with a flair for the sensational, the newspaper’s editor, Georges Clemenceau, slapped on a punchier headline. Stepping out of a department store or stepping down from a carriage, sitting at a café or standing at an intersection, pedestrians were greeted by two words that continue to resonate 125 years to the day after their first publication: “J’Accuse!”

With this exclamation, Zola’s letter transformed une affaire judiciare into l’affaire Dreyfus or, more simply, the Dreyfus Affair. It catapulted the French novelist onto the world stage at a critical moment in the history of his country, which was reeling from the forces of globalisation and industrialisation and riven by opposing understandings of its revolutionary heritage. It is thus hardly surprising that Zola’s fame rests more heavily on the letter than on his sweeping 20-volume masterpiece of literary realism, the Rougon-Macquart. It took a novelist to heave the facts of this affair into a narrative which, more than a century later, thrums with equal urgency. Moreover, as with the novels of the Rougon-Macquart, the letter thrusts onto centre-stage a lone individual swept up, and all too often swept under, the political and social, irrational and ideological forces of the modern age.

It all began with the contents of a rubbish bin. In September 1894, a cleaning woman at the German Embassy, in the pay of France’s military intelligence service, delivered her nightly harvest to her employers. Buried in the mound of discarded papers was a memorandum, known as the bordereau or note, revealing top secret advances in French artillery technology and tactics. In a frantic scramble to find its author, the war ministry’s suspicion settled on Captain Alfred Dreyfus, an officer in the High Command who stood out for his standoffishness and Jewishness.

Upon being arrested and charged, a bewildered Dreyfus denied the charges, pointing out several things mentioned in the bordereau he could not possibly have known. The seven members of the military tribunal, ignoring these inconsistencies as well as the insistence of their own graphologist that Dreyfus’s handwriting did not match the bordereau’s, unanimously found him guilty. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in solitary confinement on Devil’s Island, a malarial rock off the coast of French Guyana.

But first came a remarkable ritual of public humiliation. Dreyfus was marched into the courtyard of the École militaire, the renowned military academy a short distance from the recently erected Eiffel Tower. In the shadow of that monument to modernity, an officer preceded to snap Dreyfus’s sword — broken and soldered back together with tin the night before, to make the gesture seem effortless — and tear off his insignia — whose threads were already loosened — while a dense crowd howled with calls for the death of the “Jewish traitor!”

Two years later, as Dreyfus wasted away in solitary confinement, Colonel Georges Picquart, the newly appointed head of military intelligence, found that another missive about French military plans had ended up in the rubbish bin at the German Embassy. Moreover, the handwriting on this new document, which matched that of the bordereau, also matched the hand of Ferdinand Esterhazy, an officer notorious for his womanising and gambling.

Picquart disliked Jews as much as his many of his fellow officers did. But when his commanding officer asked him why it mattered if “this Jew remains on Devil’s Island”, Picquart replied: “Because he is innocent!” The answer earned Picquart a rapid transfer to a desert outpost in North Africa. Before he was packed off, though, Picquart vowed that he would not “carry this secret to my grave”. He then shared what he knew with Auguste Scheurer-Kestner, the leader of Dreyfusards, a small but growing coterie of politicians and writers seeking a retrial for Dreyfus.

In late 1897, Zola met with Scheurer-Kestner, who told him about Picquart’s discovery. As the mesmerised novelist listened, he glimpsed the theatrical as well as moral dimensions of the affair. “It’s thrilling!” he gasped. “It’s frightful! But it is also drama on the grand scale!” It took Zola to scale it to greatness by flipping Oscar Wilde’s sly quip that anyone could make history, but only a great man could write it. Instead, Zola showed, a man becomes truly great only by, in every sense of the word, making history.

But to make history, one must first master its details. For his novels, Zola spent weeks cramming before he began writing. Preparing his epic Germinal, he toured northern France, interviewing miners and managers, plunging into libraries as well as down mine shafts. Zola followed the same approach for “J’Accuse”. Like the Dreyfusards, he was appalled by the yawning gaps in the prosecution’s case — gaps that a clique of officers had frantically filled with forged documents. But as Zola knew, it was not enough to make the facts public. He also had to make them compelling. “Our factual accounts became poetry for Zola,” recalled Scheurer-Kestner. But Zola did not do poetry; instead, he did tragedy. And truth to say, Dreyfus’s case did resemble the tragic stuff of Zola’s fiction, peopled by fully realised characters who are eventually flattened by what Zola’s predecessor, Honoré Balzac, called the social machine.

Thus, after preparing the stage with a series of articles punctuated with the prophetic words, “Truth is on the march, and nothing will stop it,” Zola published his climactic letter. The lion’s share is devoted to a merciless exposé of the many inconsistencies in the military’s case, but what readers remember is the peroration. With incantatory cadence, Zola names names in the highest reaches of the military, preceding each of his criminal charges by the phrase “I accuse”. He then concludes with striking flourish that circles back to his earlier leitmotif: “The act I accomplish here is but a revolutionary means for hastening the explosion of truth and justice.”

Explosive, indeed. Deferring to its military, the government charged the novelist with libel and hauled him into court. Howling for the death of Zola (as well as Dreyfus, and the Jews), anti-Dreyfusard mobs clashed with police on the boulevards of Paris while squads from the Anti-Semitic League ransacked stores in the Jewish quarter of Le Marais. While Zola left France for the start of a year-long exile in England, Esterhazy left the military court that, despite overwhelming evidence of his guilt, had just exonerated him of the charge of treason, to be greeted by a cheering crowd.

None of this, however, was enough to prevent a new trial for Dreyfus. After more than four years of solitary confinement on Devil’s Island, the man who had been transformed into a symbol returned to France in 1899 and accepted a presidential pardon. An expended country tried to put The Affair behind it, and an exhilarated Zola returned to Paris. Yet his return was short-lived: on September 28, 1902, he died from asphyxiation while asleep in his bedroom. Investigators found the chimney was blocked, giving rise to rumours, never confirmed, that someone had acted on the countless death threats made by Right-wing nationalists against the writer.

But this was not the end of The Affair. In fact, it has no single ending, and “if you want a happy ending,” as Orson Welles once remarked, “that depends, of course, where you stop your story”. Stories of The Affair usually stop at the 50,000 mourners who accompanied the carriage carrying Zola’s casket to Montmartre Cemetery in 1902. Or they stop at the legal exoneration of Dreyfus in 1906, followed by his receipt of the Légion d’honneur and his reinstatement in the army. Or they stop in 1908, with the transfer of Zola’s remains to the Pantheon where, under the eyes of Captain Dreyfus, Prime Minister Clemenceau and War Minister Picquart, he was extolled for “descending from the ivory tower” and confronting “the passions of the crowd”. Zola was reborn — sacralised, really — as a public intellectual, that uniquely French creature who, armed with the certainty that comes with science and reason, offered his moral guidance to the nation.

There are, however, many other potential endings that retellings such as the Oscar-winning 1937 film, The Life of Zola, left on the cutting room floor. (Among the cut scenes were those that mentioned the words “Jew” and “antisemitism”.) Rather than concluding with the largely fictitious speech the actor Paul Muni gives in the courtroom, or the actual oration over Zola’s remains at the Pantheon, we could instead declare “It’s a wrap” with Louis Anthelme Grégori, the fanatical nationalist who shot Dreyfus at the end of the oration but succeeded only in grazing his arm. Or we could snap the clapperboard with the trial of the same would-be assassin, acquitted by a jury that accepted his claim that he had only wished to wound, not kill Dreyfus. Why not, in fact, sign off with the institutionalisation and banalisation of movements like Action française, which slapped an intellectual veneer on a virulent antisemitism that persists to this day in France’s extreme Right-wing?

And, for that matter, on France’s extreme Left-wing. Tellingly, reactionary ideologues at the turn of the century could not claim exclusive dibs on antisemitism; many socialist and anarchist thinkers were no less eager to embrace it. The founder of French syndicalism, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, insisted that the Jews, “always parasitical and fraudulent”, controlled the levers of capitalism, while the socialist firebrand Auguste Blanqui branded them as “the incarnation of swindling, usury, and rapacity” who were waging a “war to the death with the human race”.

Most telling and disturbing, though, is how the laudable passion for truth and justice soon became, as the Oxford historian Ruth Harris brilliantly traces, a lamentable passion for Truth and Justice. Not only did The Affair unify the previously warring parties on the Left — which, upon forming a government, launched a crusade against the Catholic church, expelling hundreds of orders and convents, many of which had nothing to do with politics. It also led to yet another affair, a sorry event known as the affaire des fiches. In 1904, the Ministry of Defence, with the help of Masonic lodges, secretly created files on more than 25,000 officers who, because of past involvement with the Church — including charitable activities — were now considered suspect.

This affair, which eventually led to the collapse of the government, also collapsed what remained of the idealism of those who rallied to Dreyfus. As Charles Péguy, who was both a Catholic and Dreyfusard, concluded, everything that begins in mystique ends in politique. This includes the politics of the Left no less than the Right. The French Left, Harris rightly notes, was as prone to the “dangerous dynamic” of absolutism as its opponents on the Right. What this suggests — and a glance as any news site confirms — is that The Affair, rather than having no single conclusion, is a never-ending tale. How could it be otherwise in a world where communications technologies, whose algorithms drive passions and damper reason, make the newspapers and pamphlets of fin-de-siècle France look positively fin-de-néolithique?

Seventy years ago, another novelist who moonlighted as a journalist made this point in his essay The Rebel. In a world framed by opposing ideological extremes, Albert Camus concluded, the rebel is someone who insists upon limits and refuses to surrender the centre. In a line that could serve as Zola’s epitaph — or, for that matter, his own — Camus declared: “The logic of the rebel is to want to serve justice so as not to add to the injustice of the human condition.” In the end, the rebel is a radical moderate — a phrase that is certainly oxymoronic, but even more importantly tragic. Yet it is a role whose logic is as pressing today as it was in Zola’s day.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe