‘The Holocaust trumps art every time.’ (Pantheon)

There was a great three-panel comic that the artist Art Spiegelman did for The Virginia Quarterly Review a while back that neatly encapsulates the dubious if nearly universal centrality of the Holocaust in American Jewish life. In the strip, the artist, author of Maus, the path-breaking Jews-as-mice-Nazis-as-cats Holocaust manga, hands a little treasure chest to his son, Dash — a birthday present. When his son opens the box, a horrible fire-breathing dragon wearing an Auschwitz prisoner’s striped cap, with a little extra Hitler head for good measure, breathes fire on the child and burns him. Nice gift, dad.

Still, Spiegelman’s Maus seems fated to wind up one day in its own Dead Sea Scrolls-like wing in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, which stands on the National Mall in Washington DC, a stone’s throw away from the gorgeous Yoruba crown of the American Museum of African American History. Since the Holocaust Memorial Museum opened in 1993, fewer and fewer American Jews seem to question the wisdom of putting a gruesome and terrifying act of mass murder at the centre of their collective identity. In a recent Pew Research Center study, 76% of American Jews said that “remembering the Holocaust” was a key component of what being Jewish meant to them — far ahead of other ostensible pillars of communal life such as “working for justice and equality” (59%), “caring about Israel” (45%), “having a good sense of humour” (34%), or “observing Jewish law” (15%).

The centrality of the Holocaust to American Jewish self-definition is also a surprisingly recent phenomenon. The invisible barrier that partitioned the American Jewish success story from the terrors of the Holocaust only began to dissolve in the late Seventies, with the airing of the 1978 mini-series Holocaust, starring Meryl Streep. Conceived and sold as a kind of Jewish Roots, Alex Haley’s sweeping drama about American slavery which had aired the previous year, Holocaust was seen by large mass audiences in both the US and Germany, breaking the informal ban on portraying Nazi crimes through the lives of their Jewish victims. In that same year, the Polish Jewish writer Issac Bashevis Singer, who lived in Manhattan and wrote movingly in Yiddish about the vanished world of European Jewry and the lives of émigré Holocaust survivors in America, was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature, leading to broader interest in his work in the US. The following year saw the publication of two taboo-breaking American novels that brought the Holocaust into mainstream literary culture, Philip Roth’s The Ghost Writer and William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice, both of which underlined the uneasy continuities between Europe and America (Streep also starred in the movie version of Styron’s novel).

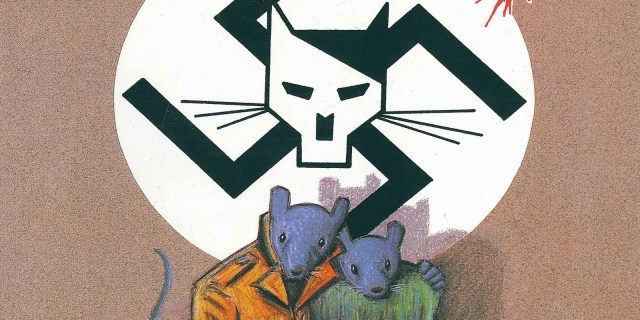

In the context of these cracks in the cultural ice, which would culminate, in 1993, with the opening of the Holocaust Museum in Washington and the release of Steven Spielberg’s film Schindler’s List, the appearance of Art Spiegelman’s autobiographical cartoon strips about Jewish mice and Nazi cats in the underground comics magazine Raw in 1980 — the strips were published in book form as Maus in 1986 — did not cause much of a stir. Yet for those of us who were kids in New York and read Raw, Spiegelman’s strips were the ultimate Holocaust Samizdat. Were they sacrilegious? Were they art?

When I asked Spiegelman that question a few years back, he sighed, and gave his stock answer: “The Holocaust trumps art every time.” Spiegelman, whose name can be translated as “art mirrors man”, is the owner of a stunningly fertile graphic imagination that over the past 40 years has produced dozens of formally innovative and often searingly self-reflective strips in various magazines, including Arcade and Raw, which he co-founded and edited with his wife, French artist and editor Francoise Mouly. In his day job at the Topps trading card company, he created and edited the Garbage Pail Kid series before moving on to a more upscale day job at The New Yorker, where he created some of the magazine’s most iconic covers of the past three decades, including a Hasid and a black woman kissing on Valentine’s Day and the famous post-9/11 “black cover”, which, when you held it at an angle to the light, showed the outlines of the vanished Twin Towers.

Spiegelman came by his interest in the Holocaust naturally enough, as a child of parents who survived Auschwitz and settled in New York City after the war. Spiegelman himself was born in Stockholm, Sweden; his brother Rysio was poisoned in a bunker in Poland along with two other small children by his aunt, so that they wouldn’t be taken to an extermination camp. When Spiegelman was 20, he was confined in a mental hospital, whereupon his mother killed herself. Spiegelman was released from a state mental institution in Binghamton, N.Y., to attend her funeral — an event that would become the basis of one of his early, devastatingly personal cartoons. Spiegelman’s father then burned his mother’s diaries about her experiences during the war and in the camps, which she had intended for her son to read after her death.

His impulse to rid himself — and his son — of the burden of the Holocaust was not unusual, either among survivors or American Jews in general. The Holocaust was largely a taboo subject among American Jews, most of whom were glad to have left Europe and the experiences of European Jewry behind, especially given the opposing fates of Europe’s Jews and America’s. Where European Jews had faced total annihilation, American Jews had gained unparalleled social acceptance in a more open and democratic country that they were eager to embrace, and which seemed increasingly, and even unusually, willing to embrace them.

The key to Jewish social acceptance in America, which included access to higher education, jobs, and housing that had routinely been denied to Jews before the war, was their military service during the Second World War. More than 600,000 American Jews fought in the Allied Armed Forces to defeat Hitler, who was both a national enemy and a particular enemy of the Jews he sought to exterminate. The fight against Hitler therefore united American nationalism and Jewish particularism in a way that helped liberate Jews from the prejudice they had suffered before the war. The Manhattan Project, which gifted the United States rather than Nazi Germany with the most terrifyingly destructive weapon known to mankind, was led by the Jewish physicist Robert Oppenheimer and a team of émigré scientists, most of whom were also Jewish, and was grounded in a theory of matter whose outstanding progenitors were physicists Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr, who were also — well, you get the point. Another half million or so American Jews fought in Korea.

The replacement of images of American Jewish wartime patriotism, heroism and strength with images of European victimhood struck Jews in the Fifties as a dubious, undesirable and even potentially dangerous trade-off. Far from being a pillar of communal identity, the Holocaust was mostly a kind of terrifying in-group secret that accompanied the great movement of Jews from urban ghettos to tennis clubs in leafy suburbs like the one that Philip Roth portrayed in Goodbye, Columbus. Speak too loudly about the Holocaust, or so the whispered communal voices suggested, and friendly post-war Americans might recall that before 1939 many of them — especially at the higher echelons of society — had been fervent antisemites. Survivors such as Art Spiegelman’s parents, who came to America after the war with numbers tattooed on their arms, speaking broken English and haunted by terrible memories, were unwanted guests at the banquet of post-war American Jewish success, bearers of the grim message that it could all vanish tomorrow.

A good part of the energy of American Jewish culture after the war can therefore be seen in part as the product of an act of profound and even generative repression of a tragedy that after all, had happened somewhere else. In Hollywood, where Jews, individually and collectively, exerted an enormous cultural presence, it took until Schindler’s List for an A-list Jewish director or executive or star to make a major film about the destruction of European Jewry. Neither The Naked and the Dead nor Catch-22, the two classic American Second World War novels, written by the Jewish novelists Norman Mailer and Joseph Heller respectively, mentioned the Holocaust. The 1959 movie version of The Diary of Anne Frank was directed by George Stevens and otherwise carefully de-natured to avoid seeming like a Jewish story.

For an American kid like Spiegelman, who was nevertheless unable to avoid the subject of the Holocaust because of the ways they had shaped his own life, it was necessary to find non-mainstream cultural forms in which to express his terrors. Spiegelman credits Mad magazine and the sensibility of its founder Harvey Kurtzman for shaping his early desire to use cartoons to express his sense that something was not entirely right with the way the world around him worked or was portrayed in mainstream acceptable culture. His first Mad anthology, which he studied with the intensity that some of his peers brought to pages of the Talmud, was a gift from his mother, the Auschwitz survivor who killed herself.

Starting in 1978, Spiegelman, then a well-known underground cartoonist, began interviewing his father about his wartime experiences. In the early Eighties, he began creating strips that narrated his father’s stories and portrayed his own relationship with his father, a miserly and compulsive yet deeply sympathetic character; the strips were published in Raw under the title “Maus”. Both the title and the device of portraying Jews as mice and Germans as cats had been used by Spiegelman before, in a three-page strip he had published in 1972 and that was later published in his collection Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!, which attracted the admiration of hundreds of dedicated alternative comics fans but few buyers.

Today, it seems clear that Maus and Maus II, Spiegelman’s continuation of the first collection, are the most powerful and significant works of art produced by any American Jewish writer or artist about the Holocaust. While their enduring popularity is a tribute to Spiegelman’s deep honesty about his emotional experience of his upbringing and of his graphic and narrative talent, it is also a reflection of the way in which the Holocaust has morphed from a threatening and largely repressed communal trauma to the glue that binds the American Jewish community together. If Art Spiegelman is a genius who created a work of searing originality and insight out of his familial and personal suffering, it is also hard not to worry about the anti-aesthetic and communal consequences of his achievement. If he is right to complain that the Holocaust trumps art, it was Maus that opened the floodgates.

Of course, Jews are hardly the only group of Americans who seek to define themselves through historical trauma. In America’s flourishing victimhood Olympics, to be a black American is to be the descendent of slaves, who were whipped and chained — even if your Nigerian parents came to America to study medicine on Fulbright Scholarships. To be Asian is to have been sent to labour camps during the Second World War — “Asian” being one of the catch-all American identity groupings like “Hispanic” that lump together the experiences of widely differing nationalities, population groups and tribes. To be gay is to be persecuted for your sexual preferences, like Oscar Wilde, or be denied treatment for Aids. In all these cases, the moral virtue and practical wisdom of inculcating identities centred around the traumatic experiences of people who, in most cases, are no longer alive is simply taken as an article of faith.

Yet Jews remain a special case, in part because the trauma inflicted on them was so recent and totalising; in part because they are in fact a tribe, with a continuous collective historical memory stretching back to the Old Testament; and in part, because they are also, simultaneously, an unabashed American success story. The apparent contradictions between the American Jewish success story and the Holocaust victimhood narrative can be unsettling, both for purveyors of victimhood ideology and for American Jews. For if historical trauma begets present-day ills, then why are Jews so successful — and were they ever truly victims? And what if Jewish success in fact begets Jewish victimhood, in which case America’s special status as a safe haven from the terrors of Jewish history is illusory?

The fact is, neither the Left nor the Right in America can get what they actually want from the Holocaust, which is a simple and gratifying victory over their political enemies. Fantasies about rural Trumpers gleefully carting liberal American Jews off to the gas chambers have more in common with fetish porn than they do with American social or political reality. Similarly, the poor inner-city teenagers who physically attack poor urban religious Jews with sickening regularity have little in common with goose-stepping would-be Übermenschen.

The eagerness with which both sides in America’s inane political wars seek to deploy the Holocaust as a weapon is not a sign of any great respect for the dead. Nor does it do anything to help living Jews, whose position as a small minority in an increasingly fractured and unstable country seems unlikely to improve anytime soon, no matter how often the Left and Right accuse the other side of being Nazis.

Perhaps Art Spiegelman’s parents understood something important about the past that today’s balkanised and trauma-obsessed Americans can no longer credit: that the greatest gift you can give your children is to free them from the past, so that they can become something new. For Art Spiegelman’s parents, the demand that they not pass on their incalculable suffering to their son was simply too great. The rest of America has no such excuse.

David Samuels contributed an essay to Maus Now, a new essay collection edited by Hillary Chute (Viking).

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe