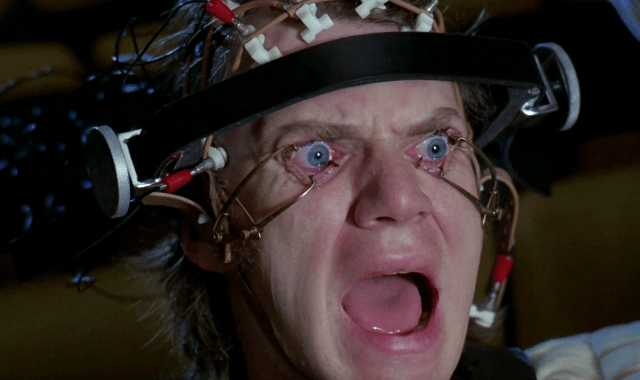

The cure for fascism (Warner Bros)

In the young, online manosphere, there is growing movement to refrain from masturbation as much as possible. This manifests itself every year in No Nut, or NoFap, November, a time for total abstinence from “fapping“, as certain online circles call it. Young men have set themselves this challenge, not out of religious conviction, but from a determination to reclaim for themselves a certain degree of self-command. It is the rare appearance of ascetic practice in a society that is at once libertine and shot through with a political moralisation of sex.

The main thrust of that moralisation has been to protect women from male sexuality; here is an instance of men seeking to protect themselves. They do so on the supposition that their vital energy has been dissipated and colonised by a culture, and an industry, of pornography that is predatory and dehumanising.

One might suppose, then, that this movement would find sympathetic allies among feminists who notice a symmetry of concerns. And surely there are such feminists. But we also hear alarm, in a register typical of today’s politics: these young men are displaying disturbing fascist tendencies.

Say what?

There may indeed be an overlap between the no-nutters and the online Right. That is certainly how it is characterised by those who find it threatening. If there is such an overlap, the common thread is surely the reappearance of “vitalism” as a point of orientation for young men who feel smothered and demoralised in a society that has little use for male energies. European vitalist thinkers include Friedrich Nietzsche and Henri Bergson. In the American context, the vitalist tradition is represented by figures such as Teddy Roosevelt, William James and, arguably, Mohammed Ali. Its most vivid recent articulation may be found in the movie Fight Club, which depicted a masculinist revolt against the androgynising and enervating effects of a consumerist, white-collar existence that offers little place for male solidarity. Its current avatar is the notorious, beloved Bronze Age Pervert (BAP to his fans). As the historian TJ Jackson Lears points out in his forthcoming book Animal Spirits, the vitalist orientation does not appeal solely to men. It may be found also in “sex-positive” feminists going back to Margaret Sanger and Mabel Dodge in the 19th century.

Whatever meaning and political valence the no-fap movement has for its adepts, the journalistic Left’s ready identification of sexual self-regulation with “fascism” has a definite genealogy. Retracing this gives us a glimpse into a fascinating chapter of 20th-century social engineering, a programme of sexual “liberation” that is still with us and can feel, if not obligatory, certainly on the agenda for all who would be well-adjusted. Acquaintance with this history should disabuse us of the idea that the sexual revolution was an entirely organic eruption of cultural change, and that it happened in the Sixties. Sexual liberation was the goal of a therapeutic para-state whose organs sprang into existence almost overnight at the conclusion of the Second World War. Its political purpose was to forestall the possibility of fascism in the United States. It would be too simple to say the sexual revolution was a government psy-op, but neither has the role of government been adequately appreciated. With the spectre of fascism once again haunting the American political imagination, and attendant worries in some quarters about inadequate masturbation, this is an episode worth revisiting.

In the early Thirties, one wing of the psychoanalytic movement splintered off and became politicised under the leadership of Wilhelm Reich. Reich was convinced that fighting fascism would require a psychological transformation of the entire German population. Their susceptibility to authoritarian politics and attraction to the Fuhrer were due to the unhealthy festering of irrational forces in individual psyches, rooted ultimately in sexual “repression”. Through the efforts of Archibald MacLeish, arch-WASP literary man of the Ivy League and liberal activist, these ideas gained influence in the American security services during the war, and particular the OSS, which was planning for the reeducation of the Germans upon their defeat and subsequent military occupation. And, in fact, the US-led Allied High Commission took up this project of Freudian political therapy in its rule over the defeated Germans, which lasted until 1955.

To put the matter crudely, the Germans were going to have to start masturbating more. More seriously, the working-class family, with its sharply distinguished sex roles and ideal of a strong father, was found to be at the root of the political problem.

Reich called himself a Freudo-Marxist. The term announced a political program that would require nothing less than a moral revolution, working at the deepest level of the individual. For society is not only unjust, it is sick. His project might reasonably be compared with that of Rousseau, whose popular works of sentimental reeducation supplied (however wittingly) the emotional idiom of the French Revolution, and the character ideal its enthusiasts sought to realise through that cataclysm.

Psychoanalysis was to be used for revolutionary purposes. Conventional Marxists made economic conditions the focus of their science; the Freudo-Marxist focused on moral conditions. Where the consummation of the Marxist project brings the withering away of the state, Reich’s political therapy required nothing less than the dissolution of the superego, that “sham social surface” and impediment to the instincts, which are taken to be pure and good. Here, too, we see an echo of the French Revolutionists’ Rousseau-inspired cult of sincerity or self-exposure. Let it all out.

The public tyranny of capitalist domination and the private tyranny of conscience form a circle of mutual support, on Reich’s view. Revolution cannot succeed unless it works ruthlessly on the psychological level. Indeed, revolution carried out on the level of economy and politics alone leads to bourgeois “defense reactions”, the most disastrous of which is fascism.

It is in the family that repressive authority is incubated and reproduced. Someone less invested in moral revolution may object that it is in the family that our faculties of moral perception develop, a gradual training of the affections whereby the child begins to apprehend an objective order of good. If all goes well, he comes to prefer virtue over vice through the mediating guidance and concern — the authority — of his parents. Reich would entirely agree, but with an opposite thrust. That is, he agrees that the moral sense is a product of authority, but insists that authority can only be repressive, never generative. It is always exercised self-interestedly, never generously for the good of another. Morality is the very thing that needs to be liquidated in the revolution.

As Philip Rieff puts Reich’s point, “A revolution must sweep out the family and its ruler, the father, no less cleanly than the old political gangs and their leaders…. The destruction, then, of the ancient mystique of fatherhood defines the revolutionary task.”

All this may be interesting as a nugget in the history ideas, but does it have any relevance to today’s politico-sexual landscape? Reich wasn’t just one more radical crank, fascinating to intellectuals but of little consequence. In fact, he was part of a larger intellectual movement that gained a substantial institutional footing in the United States in the decade immediately after Second World War.

One such institutional perch for Freudian ideas was the Army. The scale and intensity of violence in the Second World War are difficult for us to comprehend today. It was a war in which the civilian populations of entire cities were incinerated in a matter of hours. For B-17 bomber crews in the European theatre, the odds of surviving a complete tour of 25 missions was about 50% in 1943. We should not be surprised that of those American soldiers removed from service before completing their tours, approximately half were deemed unfit for psychiatric reasons. Sustained, abject terror will do that to a man. Of those who completed their tours of duty, many were deeply troubled.

Immediately after the war, the War Department undertook a study to determine the causes of psychiatric breakdown in American soldiers, using interviews to probe their minds. According to Adam Curtis’s BBC documentary The Century of the Self, the study was conducted under the guidance of refugee psychoanalysts from central Europe. The focus of these interviews, however, was not the soldiers’ wartime experiences but their childhoods. The stress of combat had merely triggered buried memories.

And what were the findings of the study? The problems of these broken soldiers were due, not to violence, but to the repression of violence, and of sexuality, typical of family life. Small town life in middle America, it turned out, was a breeding ground of precisely those unhealthy character traits that, under the right conditions, give rise to fascist movements.

In The Century of the Self, one Martin Bergmann, a US Army psychoanalyst from 1943 to 1945, speaks into the camera in a thick Mitteleuropa accent, recounting the train trip he took from the East Coast to the West Coast of his newly adopted country and his fascination with “what goes on in all those little towns”. His work gave him “a privileged tour into the inner soul of America”. What he found is that “the ratio between the irrational and the rational in America is very much in favor of the irrational”. It is “a much more problematic country” then you would think, given its cheerful self – image.

The problem with Americans was that they were latent Nazis. Presumably this came as a surprise to those soldiers who had lately placed their young bodies in the service of a national effort to defeat the Nazi regime.

In 1946, President Truman declared a mental health crisis in America, a watershed moment in the emergence of the therapeutic state. As Curtis put it, “the Second World War would utterly transform the way governments saw democracy, and the people they governed”. The American government, in particular, would turn to the Freud family for guidance on how to control the enemy within, convinced that “hidden under the surface of their own population were the same dangerous forces” that had led to the death camps. The inner lives of Americans were now something that needed to be managed. Anti-fascism in the United States would be a science of social adjustment working at a deep level of the psyche, modeled on the occupation government’s parallel effort in Germany.

“What is needed is a human being that can internalise democratic values,” said Bergmann, the US Army psychiatrist. “Psychoanalysis carried in it the promise that it can be done. It opened up new vistas as to how the inner structure of the human being can be changed so that he becomes a more vital, free supporter and maintainer of democracy.”

One must pause whenever the word “democracy” is used in such utterances. In fact, a central premise of midcentury social management was precisely that the free contest of responsible citizens in democratic politics does not reliably produce a properly “democratic” personality. “Changing the inner structure of the human being” so he becomes a reliable supporter of a political program — creating a New Man — was supposed to be the hallmark of totalitarianism, but evidently appeared necessary to some significant part of the American political establishment. Liberalism would have to become, not anti-totalitarian, but rather a countervailing project of man-making, no less total in its reach.

Following passage of the National Mental Health Act of 1946, its principal architects Karl and Will Menninger trained an army of hundreds of psychiatrists to fan out across America. In the late Forties, “psychological guidance centers” were set up in hundreds of towns, staffed by psychiatrists who “thought it was their job to control the hidden forces inside millions of Americans”, according to Adam Curtis. Thousands of counselors offered marriage guidance; social workers visited homes. As Robert Wallerstein of the Menninger Foundation put it in The Century of the Self, the operating assumption in these times was that “you could really change people. And you could change them almost in limitless ways.”

Freud’s daughter Anna was the guiding figure for the new para-state organs of psychological adjustment. Heir to her father’s movement, “her whole life rotated around the spreading of psychoanalysis”, according to her nephew Anton Freud. Curtis points out that this evangelising spirit marked a shift from Sigmund Freud’s efforts to understand the psyche to Anna Freud’s mission to modify the psyche. While Sigmund had a tragic view of the human being, emphasising the irreducible conflict between self and society, Anna had a reformer’s faith in the efficacy of psychoanalysis as a technology of personal and social improvement.

Let’s step back for a moment and consider the political soil in which these imported Freudian seeds would germinate. In his 1991 book, The True and Only Heaven, Christopher Lasch notes that “around the turn of the century, social reformers began to refer to themselves as progressives rather than liberals”. He quotes a work titled Liberalism in America (1919) in which Harold Stearns offered a portrait of the ideal political personality as “scientific, curious, experimental…urbane, good-natured, non-partisan, detached”. I don’t know if they had yard signs back then, but these were the traits of what H.L. Mencken called “the civilized minority”. They were tied to specific political positions, opposition to which could be taken as signs of ignorance, superstition, and intolerance.

Lasch writes that in the early decades of the 20th century, liberals convinced that the mass of their fellow citizens were impervious to reason believed they “would either have to master the new techniques of advertising and propaganda, … or seek to minimise the influence of public opinion on policy, … and see to it that policy – making was conducted exclusively by experts.”

In fact, both strategies became important. On the policy front, Woodrow Wilson addressed the growing gulf between popular preferences and progressive policy goals (recently exacerbated by an expansion of voting rights to less enlightened elements in society) by transferring political initiative and discretion from the democratically elected legislature to the bureaucracies of the nascent administrative state, where matters could safely be decided by experts. But it is the propaganda front that concerns us here, as it intersects intimately with the premises of Freudian political therapy.

The art of propaganda had taken great strides forward during the First World War, when popular fervour against “the Hun” was whipped up in the United States to support an unprecedentedly destructive war, the point of which nobody could say. Edward Bernays, one of the architects of the wartime propaganda effort, turned to advertising after the war as the logical venue for his craft (he would later put his talents in the service of the CIA). A nephew of Sigmund Freud, with whom he was intellectually close, Bernays developed his art on the premise that human beings are irrational, subject to subconscious drives that swamp any capacity for reflective deliberation.

Between the wars, liberals in the United States were watching developments in Europe with unease as fascist movements began to get traction. In the United States, there was significant sympathy with European fascist movements, not only on the anti-semitic Right but also on the New Deal Left. The putative irrationality of ordinary people was beginning to look like an ominous political fact. The premise of irrationality offered a lever of social control through the manipulation of subconscious drives, while the gathering political threat provided a reason for the principled use of this lever to steer the masses away from dangerous territory.

In this period, Walter Lippmann and H.L. Mencken were influential among liberals in their embittered view of the public as unreliable partners in the democratic project. What was wanted was democracy without a demos. This becomes less paradoxical once you understand that the term “democracy” was serving then, as it does now, as a term of approbation naming something in no way dependent upon the procedures of representative government, and a character ideal defined in explicit opposition to the deplorable masses. The mantle of “democracy” was the homespun worn by liberalism when it went about in public, seeking a wider political legitimacy than would otherwise be extended to the preoccupations of a civilised minority pursuing “experiments in living”, to use J.S. Mill’s formula.

Immediately after the Second World War, this distrust of the people among America’s Northeastern Protestant liberals got joined to an imported version brought by European émigré intellectuals who had narrowly escaped death at the hands of a Nazi murder state that enjoyed a kind of terrifying democratic mandate, in the narrow procedural sense of winning the support of a majority in its rise to power. These émigrés were therefore understandably ill-disposed to the masses, and toward democracy in its primary sense of rule by the people.

The concerns of this politicised psychoanalytic movement got grafted onto the regime of technocratic administration that liberals had been advancing in the US for half a century. The fateful consequence, clearly visible in retrospect, is that the administrative state became the therapeutic state, with the “helping professions” serving as expert handmaidens to the new regime. Flush with victory in its first ideological war, confident in the surfeit of legitimacy that comes with victory, the government took up anti-fascism as a wider mandate of moral and social transformation.

At the same time, the academic discipline of sociology took an activist turn. The American-led occupation government in Germany favoured sociology departments in universities as a vehicle of German re-education. The effort was led by scholars returning from forced exile in the United States, some of them connected to the Frankfurt School. In the US, five collaborative works, together titled Studies in Prejudice, were sponsored by the American Jewish Committee’s Department of Scientific Research. Of these, The Authoritarian Personality (1950) was the most influential. “No volume published since the war in the field of social psychology has had a greater impact on the direction of the actual empirical work being carried on in the universities today,” wrote Nathan Glazer in Commentary in 1954. The research was conducted by a group at Berkeley headed by Theodore Adorno of the Frankfurt School.

The massive study offered a set of criteria to discern personality traits said to indicate authoritarian tendencies. With the impressive machinery of social science, it ranked Americans on an “F Scale” where F stands for pre-fascist. An early version of its questionnaire to detect right-wing personality traits, deployed in California in 1947, was used in police work and in the psychological assessment of public school students.

The survey built on earlier studies conducted in Germany at the Institute for Social Research, but with a different slant. Openly Marxist in its original, Frankfurt iteration, it had placed its subjects on an authoritarian personality/revolutionary personality axis. (To the extent you are not revolutionary, you are authoritarian.) Repackaged for America, this was changed to an authoritarian personality/democratic personality axis. The shift of terms was well-attuned to the political idiom of the study’s American sponsors: in the United States, the vanguard named itself “democratic” rather than revolutionary.

Which is not to say that TAP’s adaptation of Freudo-Marxism to the American context was merely superficial. No less a figure than Peter Berger failed to see that an important shift had occurred between Reich’s The Mass Psychology of Fascism (addressed to a German audience in 1933) and The Authoritarian Personality (addressed to an American audience in 1950). Berger saw the latter as continuing the attack on the family coming from the Communist Left, which found the roots of “authoritarianism” in bourgeois-capitalist family structure. Accordingly, Berger saw the 1950 American volume as lending support to the commune movement that was gaining traction in Western Europe and America. Christopher Lasch points out that, in fact, “the general conclusions reached by Adorno and his collaborators fitted comfortably into a liberal consensus that condemned the allegedly repressive family patterns typical of working-class and lower-middle-class milieux and advocated as an alternative not ‘communes’ but the enlightened family patterns already adopted by the professional and managerial classes”. (451) These were the very patterns that would be demanded by capitalism in the coming postindustrial economy, which would accelerate an ongoing erasure of sexually differentiated forms of work.

Items contributing to the working class’s high scores on the F-scale included a belief in distinct sex roles and a “rigid” sexual morality. A woman with a “self-image of conventional femininity,” for example, was sure to develop an “underlying bitterness” which often took “deviously destructive forms”. We can note as well that, from the perspective of late capitalism, someone “clinging to femininity” is someone who has failed to become an all-purpose “human resource,” a labor unit minimally prone to pregnancy and maximally adaptable to the workplace.

Rosie the Riveter, that well-muscled emblem of the munitions economy, was one of the government’s most successful propaganda campaigns. In Norman Rockwell’s magnificently butch, 1943 image of Rosie for the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, she has her foot resting on a copy of Mein Kampf. She would become the hero of capitalism’s next stage, in which feminism plays a structural role. The type of social science pioneered by TAP would provide expert grounds for the emerging bourgeoise sexual morality, in which sexual difference itself is viewed as a hangover from a lower stage of human development.

Another trait that earned one a high rank on the F-scale was a “punitive” and “moralistic” style of child-rearing. As Lasch writes, “The Authoritarian Personality revealed more about the enlightened prejudices of the professional classes than about authoritarian prejudices among the common people” who “may have good reason to… reject a middle-class conception of easy-going parental discipline.”

Rather than consider the pros and cons of sexually conservate attitudes, the authors of TAP treated them as manifestations of a “social disease”. Lasch points out that this influential work “substituted a medical for a political idiom and relegated a broad range of controversial issues to the clinic — to ‘scientific’ study as opposed to philosophical and political debate. This procedure had the effect of making it unnecessary to discuss moral and political questions on their merits.”

Around this same time, Alfred Kinsey released the first of the Kinsey Reports on Americans’ sexual practices (1948). It was a publishing phenomenon that had no precedent for sales in the 20th century and became the focus of intense public discussion. Kinsey understood his work to be serving a “mass psychotherapeutic function”, namely, the eradication of shame. He also assimilated the nascent concept of the “authoritarian personality” to lingering sexual moralists of various stripes. Kinsey relied on his status as an entomologist (who just happened to turn his attention from beetles to humans) to claim for himself the persona of a disinterested man of science, rather than a cultural crusader.

In TAP and its antecedents we see the ground laid for a novel politico-cultural consciousness. It would become apparent only in the next cohort, the Baby Boom, perhaps because this consciousness required a generation of conditioning by government therapy and activist social science to achieve: we are groovy astronauts of the libido (as against our repressed parents). Whatever the reality of their individual mindsets, which are no doubt as various as that of any other generation, this is the official story told about the Boomers by their self-appointed spokespersons. At the same time, a new “professional managerial class” arose that would have a deep identification with expertise as title to rule and source of class solidarity

This history is important not least for helping us to see that the century-long colonisation of ordinary people’s moral judgment by psychology, dating from the rise of the social worker in the 19th century, and more broadly the idea that common sense should defer to expertise located in a scientific clerisy, got a big boost from the psycho-sexual turn that anti-fascist politics took after the Second World War. Initiatives by the federal government spawned a wider apparatus of psychological adjustment, located in schools (above all, sex education), HR departments and any institution devoted to forming and policing character according to the priorities of a vanguardist minority. Given mid-century America’s institutional investment in fighting fascism, it became invested also in construing the world in such a way as to justify that investment. The world has ever since been saturated with something like fascism, however invisible it may appear to most people — especially after our grandfathers had defeated the real thing on the battlefields of Europe.

The valour of that effort was borrowed by social engineers and attached to their own campaign. The military campaign had required a self-confident and still mostly self-governing people to risk their lives on behalf of human dignity. The domestic campaign required cultivation of a diminished picture of the human subject, now viewed as an irrational tangle of psycho-sexual compulsions. However partial and inadequate the new anthropology, it became “too big to fail”. The politics of anti-fascism have proven highly elastic, adaptable to the needs of an expanding, therapeutic para-state that has not hesitated to substitute morally cognate terms such as racism and sexism for the original. These too are expressions of dark irrationality, and cunningly increase in society precisely by appearing to decrease.

With this pocket history in hand, we can speculate as to why the no-fapping movement could cause alarm. Keeping the appetites at a high pitch of activity, stimulating desire and then satisfying it, can serve as a political soporific. Porn may function as a soma of the masses and in particular of the male— that toxic element in society that has lately attracted special interest from the organs of political therapy. Untoward eruptions of ascetic self-command are inconvenient to the governing anthropology; they would seem to cast doubt on both the need for, and the means of, social management. Reciprocally, for men and women both, the experience of self-command can create a taste for more, and possibly even lead to curiosity about a corresponding political possibility long thought obsolete — that of self-government.

This essay is the first in a series I am calling the Archedelia Project.

***

Order your copy of UnHerd’s first print edition here.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe