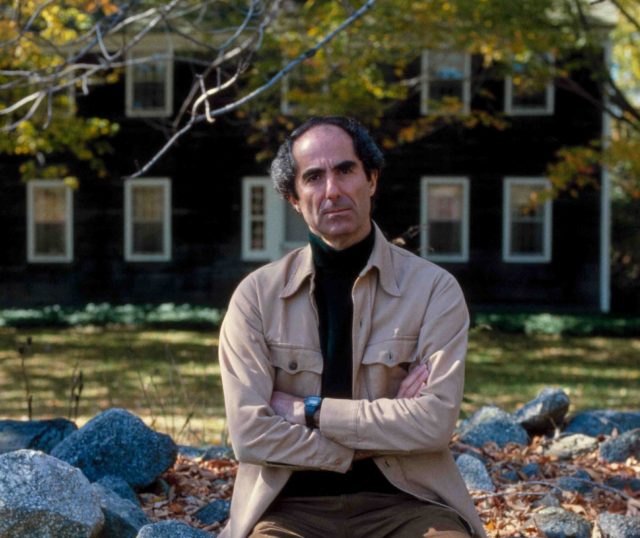

Don’t talk to him about destiny (Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Perhaps too much of Philip Roth’s energies were devoted to explaining or defending himself. You could not be with Philip for any period of time before he would enlist you in the agenda of “defending” him — against a plethora of critics, “feminists”, eventually a celebrity ex-wife.

Interest in Roth was universal. It was understood that my interview with him, conducted in his midtown Manhattan apartment, could have been published, perhaps, in the New Yorker, or the New York Times, or Harpers. Yet, Philip granted this interview to me — a friendly acquaintance rather than, at the time, a friend — for the inaugural issue of the Ontario Review, which my husband Raymond Smith assembled, with my assistance, in 1974. What a gift, from Philip!

Today, the East Eighties near the Metropolitan Museum is a residential Manhattan neighbourhood where townhouses might sell for $50 million. At the time, Philip’s (rented) apartment was certainly attractive, with high ceilings, views of a leafy street, floor-to-ceiling built-in bookcases. Most distinctly I remember the melancholy Kafka photograph, identical to the one I had taped to a wall of my room as an undergraduate at Syracuse University, and the striking artwork by Philip Guston, whose “KKK” paintings would soon be as controversial as Roth’s work.

On a bulletin board in Roth’s study are a few fan letters, including an enthusiastic tribute from Anthony Burgess, and a cartoon, probably from The New Yorker, that shows a middle-aged librarian screaming to an assistant, as flames rage around them in a library: “Don’t bother with Philip Roth! Save Galsworthy!”

What follows is an abridged version of the conversation we had.

***

JCO: Your first book, Goodbye, Columbus, won the most distinguished American literary honour — the National Book Award — in 1960; you were 27 years old at that time. A few years later, your third novel, Portnoy’s Complaint, achieved a critical and popular success — and notoriety. That must have altered your personal life, and your awareness of yourself as a writer with a great deal of public “influence”.

Do you believe that your sense of having experienced life, its ironies and depths, has been at all intensified by your public reputation? Have you come to know more because of your fame? Or has the experience of enduring the bizarre projections of others been at times more than you can reasonably handle?

ROTH: My public reputation — as distinguished from the reputation of my work — is something I try to have as little to do with as I can. Outside of print I happen to lead virtually no public life at all. I don’t consider this a sacrifice, since I never much wanted one. Nor have I the temperament for it — in part this accounts for why I went into fiction-writing (and not acting, which interested me for a while in college) and why writing in a room by myself is practically my whole life. I enjoy solitude the way some people I know enjoy parties.

I take no pleasure at all in being a creature of fantasy in the minds of those who don’t know me — which is largely what the “fame” you’re talking about consists of. As a writer I want to be recognised for what I consider good in my writing — which is something different from being recognised on the street or by the head waiter.

Since parties are to “bizarre projections” what the swamp is to the malaria mosquito, I by and large don’t go to them. I generally don’t give interviews to journalists, not even into tape-recorders; it seems pointless. Whatever one says is invariably reduced to 15 words, wrenched from context, and as often as not appears in print sounding like a translation from Chinese, unidiomatic Chinese. Anything about my work I want anybody else to know, or want to figure out for myself, I write down.

Almost the whole of my life in public takes place in a classroom — I teach one semester of each year. My public reputation sometimes accompanies me now into the classroom, but usually after the first few weeks, when the students have observed that I have neither exposed myself or set up a stall and attempted to interest them in purchasing my latest book, whatever anxieties or illusions about me they may have had begin to recede, and I am largely allowed to be a literature professor instead of Famous.

I have to talk about the books I’m reading — if I don’t my reading tends to get away from me and becomes relatively useless — and as it has turned out, a college classroom containing half a dozen smart undergraduates is one of the few places I have found in my travels where it is possible to have a coherent conversation about a book for more than three minutes at a stretch. And if it is not always brilliant conversation, it is at least responsible — which is to say, one, we have all actually read the book under discussion and even thought a little about it, and two, since the students are not privy to the latest information about the author and his wife, or his agent’s wife, or his agent’s wife’s lover’s agent, we are usually able to go an astonishing one hundred and ten consecutive minutes sticking to the subject at hand.

So: by keeping to the way of life that’s always served me best, I have been able by and large to cut myself loose from “the destiny of ‘Philip Roth’”. He goes his way and I go mine, and to tell you the truth, the less I hear about him the better.

JCO: Since you have become fairly well-established (I hesitate to use that unpleasant word “successful”), have less-established writers tried to use you, to manipulate you into endorsing their work? Do you feel you have received any especially unfair or inaccurate critical treatment? I am also interested in whether you have come to feel more communal now than you did when you were beginning as a writer.

ROTH: No, I haven’t felt nor have I been “manipulated” into endorsing the work of less-established writers. I don’t like to give the kind of “endorsements” that publishers prefer for advertising or promotion purposes — not because I’m shy about my enthusiasms, but because I can’t say in 15 or 20 words what I find special or noteworthy about a book. Generally, if I particularly like something I’ve read, I write to the writer directly. At times, however, when I’ve been especially taken by an aspect of some writer’s work which it seems likely is going to be overlooked or neglected, I’ve tried to help by writing longish paragraphs for the writer’s hard-cover publishers, who always promise to use the “endorsement” in its entirety. So far, they always have, though eventually — since it’s a fallen world we live in — what started out as 75 words of critical appreciation seems to wind up on the paperback edition cover as a two-word cry of marquee ecstasy: “Best damn!” “Not since!” and so forth.

In 1972, Esquire, for a feature they were planning, asked four “older writers” (as they called them), Isaac Bashevis Singer, Leslie Fiedler, Mark Schorer and myself, each to write a brief essay about a writer under 35 he admired. I chose Alan Lelchuk, whom I’d met when we were both guests over a long stretch at Yaddo, and whose novel American Mischief I’d read in manuscript. I restricted myself to a somewhat close analysis of the book, which, though it hardly consisted of unqualified praise, nonetheless caused some consternation among the Secret Police. One prominent newspaper reviewer wrote in his column something to the effect that “you would have to understand the Byzantine politics of the New York literary world” to be able to figure out why I had written my 1,500-word essay, which he described as “a blurb”. It didn’t occur to him that somebody whose life’s-work is writing fiction might simply be interested in what a “younger” writer was trying to do, and when given the opportunity, had chosen to talk about his interest in print. But then that one might have an analytical, rather than a political purpose, is invariably beyond the comprehension of those who protect us Americans against subversive conspiracies.

In recent years I’ve run into somewhat more of this kind of “manipulation” — malicious hallucination mixed with childish naivete and disguised as Inside Dope — from marginal “literary” journalists (“the lice of literature,” as Dickens called them) than from working writers, young or established. In fact, I don’t think there’s been a time since graduate school when genuine literary fellowship has been such a valuable and necessary part of my life. Fortunately I’ve almost always had at least one writer I could talk to turn up wherever I happened to be teaching or living; novelists are as a group the most interesting readers of novels that I have yet to come across.

In a sharp and elegantly angry little essay called “Reviewing”, Virginia Woolf once suggested that book journalism ought to be abolished (because 95% of it was worthless) and that the serious critics who do reviewing ought to put themselves out to hire to the novelists, who happen actually to have a strong interest in knowing what an honest and intelligent reader thinks about their work. For a fee the critic — to be called perhaps a “consultant, expositor or expounder” — would meet privately and with some formality with the writer, and “for an hour,” writes Virginia Woolf, “the consultant would speak honestly and openly, because the fear of affecting sales and of hurting feelings would be removed. Privacy would lessen the shop-window temptation to cut a figure, to pay off scores.”

How sensible and human! It surely would have seemed to me worth $100 to sit for an hour with Edmund Wilson and hear everything he had to say about a book of mine — nor would I have objected to paying to hear whatever Virginia Woolf might have had to say to me about Portnoy’s Complaint. Nobody minds swallowing his medicine, if it is prescribed by a real doctor. One of the nicer side-effects of this system is that since nobody wants to throw away his hard-earned money, most of the quacks and the incompetents would be driven out of business.

Until this arrangement becomes the custom, I’ll continue to look to a few writers whom I admire also as readers, to help mitigate my own feelings of isolation. “A sense of unspeakable security is in me at this moment, because of your having understood the book.” Melville to Hawthorne, in a letter about Moby Dick. Just the sort of professional intimacy and trust that is signalled by this simple outpouring of gratitude from one isolated writer to another seems to me the best thing we have to give one another.

As for “especially unfair critical treatment” — of course my blood has been drawn, my anger roused, my feelings hurt, my patience tried, and in the end, I have wound up enraged most of all with myself, for allowing blood to be drawn, anger aroused, feelings hurt, patience tried. When the “unfair critical treatment” has been associated with charges just too serious to ignore — accusations against me, say, of “anti-semitism” — then, rather than fuming to myself, I have answered the criticism at length and in public. Otherwise, I fume and forget it; and keep forgetting it, until actually — miracle of miracles — I do forget it.

JCO: Was it you who wrote about a boy who turned into a girl? How would that strike you, as a nightmare possibility? Could you — can you — comprehend, by any extension of your imagination or your unconscious, a life as a woman? A writing life as a woman? I know this is speculative, but had you the choice, would you have wanted to live your life as a man, or as a woman (you could also check “other”!)?

ROTH: Both. Like the hero-heroine of Orlando. That is, sequentially (if you can arrange it) rather than simultaneously. It wouldn’t be much different from what it’s like now, if I wasn’t able to measure the one life against the other. It would also be interesting not to be Jewish, after having spent a lifetime as a Jew. Arthur Miller imagines just the reverse of this as “a nightmare possibility” in Focus, where an anti-semite is suddenly taken by the world for the very thing he hates. But I’m not talking about mistaken identity or skin-deep conversions, but magically becoming totally the other, all the while retaining knowledge of what it was to have been one’s original self, wearing one’s original badges of identity.

In the early Sixties I wrote a not un-funny (though not very good) one-act play called Buried Again, about a dead Jewish man who when given the chance to be reincarnated as a goy, refuses and is consigned forthwith to oblivion. I understand perfectly how he felt, though if in the netherworld I am myself presented with this particular choice, I doubt that I will act similarly. I know this will produce a great outcry in Commentary, but, alas, I shall have to learn to live with that the second time around as I did the first.

Sherwood Anderson wrote “The Man Who Turned Into a Woman”, one of the most beautifully sensuous stories I’ve ever read, where the boy at one point sees himself in a barroom mirror as a girl, but I doubt if that’s the piece of fiction your question is referring to. Anyway, it wasn’t me who wrote about such a sexual transformation, unless you’re thinking of My Life as a Man, where the hero puts on his wife’s undergarments one day, but just, as it were, to take a sex break.

Of course, I have written frequently about women, some of whom I identified with strongly and, as it were, imagined myself into, while I was working. In Letting Go there’s Martha Reganhart and Libby Herz; in When She Was Good, Lucy Nelson and her mother; and in My Life as a Man, Maureen Tarnopol and Susan McCall. However much or little I am able to extend my imagination to “comprehend . . . life as a woman” is demonstrated in those books.

I never did much with the girl in Goodbye, Columbus, which seems to me apprentice-work and rather weak on character invention all around. Maybe I didn’t get very far with her because she was cast as a pretty imperturbable type, a girl who knew how to get what she wanted and to take care of herself, and as it happened, that didn’t arouse my imagination much.

Besides, the more I saw of young women who had flown the family nest, the less imperturbable they seemed. Beginning with Letting Go, where I began to write about female vulnerability, and to see this vulnerability not only as it determined the lives of the women — who felt it frequently at the very centre of their being — but the men to whom they looked for love and support, the women became characters my imagination could take hold of and enlarge upon. How this vulnerability shapes their relations with men (each vulnerable, to be sure, in the style of his gender) is really at the heart of whatever story I’ve told about these seven woman characters.

JCO: In parts of Portnoy’s Complaint, Our Gang, The Breast, and most recently in your baseball extravaganza, The Great American Novel, you seem to be celebrating the sheer playfulness of the artist, an almost egoless condition in which, to use Thomas Mann’s phrase, irony glances on all sides. There is a Sufi saying to the effect that the universe is “endless play and endless illusion”; at the same time, most of us experience it as deadly serious — and so we feel the need, indeed we cannot not feel the need, to be “moral” in our writing.

Having been intensely “moral” in Letting Go and When She Was Good, and in much of My Life as a Man, and even in such a marvellously demonic work as the novella “On The Air”, do you think your fascination with comedy is only a reaction against this other aspect of your personality, or is it something permanent? Do you anticipate (but no: you could not) some violent pendulum-swing back to what you were years ago, in terms of your commitment to “serious” and even Jamesian writing?

ROTH: Sheer Playfulness and Deadly Seriousness are my closest friends; they are the ones I take walks with in the country at the end of the day. Other people on country roads have dogs for companions, I have them. I am also on friendly terms with Deadly Playfulness, Playful Playfulness, Serious Playfulness, Serious Seriousness, and Sheer Sheerness. From the last, however, I get nothing; he just wrings my heart and leaves me speechless.

I don’t know whether the works you call “comedies” are so “egoless”. Isn’t there really more “sheer” self in the ostentatious display and assertiveness of The Great American Novel than in a book like Letting Go, say, where a devoted effort at self-removal and self-obliteration is necessary for the kind of investigation of self that goes on there? I think that the “comedies” may actually be the most ego-ridden of the lot; at least they aren’t exercises in self-abasement.

What made writing The Great American Novel such a pleasure for me was precisely the self-assertion that it entailed — or, if there is such a thing, self-pageantry. (Or will “showing off” do?) At any rate, all sorts of impulses that I might once have put down as excessive or frivolous or exhibitionistic, I allowed to surface and proceed to their destination. When the censor in me rose responsibly in his robes to say “Now look here, don’t you think that’s just a little too—” I would reply, from beneath the baseball cap I often wore when writing that book, “Precisely why it stays! Down in front!”

The idea was to see what would emerge if everything that was “a little too” at first glance was permitted to go all the way. I understood that a disaster might ensue (some have informed me that indeed it did) but I tried to put my faith in the fun that I was having. Writing as pleasure. Enough to make Flaubert spin in his grave! When manic inspiration flagged, I took trips up to Cooperstown and stayed there for a few days at a stretch, wandering around by myself in the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. I held Babe Ruth’s tattered little glove in my own hand, and watched the movie version of Abbott and Costello’s “Who’s on First” routine, as attentive and worshipful as a Catholic at Lourdes.

Admittedly, I was bolstered along the way with a certain amount of good old-fashioned modernist épater-ing. Whenever, in uncertain moments, I wondered what “they” would make of all this horseplay, I would answer my doubts with a cryptic “Fuck them”. It was only fitting that when The Great American Novel appeared, “they,” for the most part, said: “And fuck you too, bud.”

Right now, nothing is cooking; at least none of the aromas have as yet reached me. For the moment this isn’t distressing; I feel (again, for the moment) as though I’ve reached a natural break of sorts in my work, nothing nagging to be finished, nothing as yet pressing to be begun — only bits and pieces, fragmentary obsessions, bobbing into view, then sinking, for now, out of sight.

Book ideas usually have come at me with all the appearance of pure accident or chance, though by the time I am done I can see that what has taken shape was actually spawned, in a very determined way, by the interplay between my previous fiction, recent undigested personal history, the circumstances of my immediate, everyday life, and the books I’ve been reading and teaching.

The continuously shifting relationship of these elements of experience brings my subject into focus, and then the self-conscious literary brooding that occupies most of my waking hours eventually suggests to me the means by which to take hold of the material. I use “brooding” only to describe what this activity apparently looks like; inside, actually, I am feeling very Sufi-sticated indeed.

***

Roth reads two newspapers a day and watches television news-broadcasts frequently; at the time of my visit, he was, like nearly every New Yorker I encountered, obsessed with the intricacies and continuing revelations of the Washington political scandals. A cynic once said that no one would ever go bankrupt underestimating the intelligence of the American public, and so too it is probable that no one will ever go far wrong underestimating the intellectual and moral character of the typical American politician. But years ago, Roth raised the question: How can American writers, especially satirists, keep pace with ordinary reality in our time?

The serious writer, of course, chooses to concentrate upon intensely private, personal experiences, in which larger social or political events may be reflected, but kept at a distance (as they are in our own lives); the novel is a work of craftsmanship, an art, which makes it a more permanent and valuable phenomenon than the daily newspaper.

My Life as a Man is in many ways the antithesis of Roth’s more “public”, extroverted works, in that it concentrates upon the comically grotesque experiences of a man who, in his early twenties, was tricked into marrying a woman he did not love. It can be read on at least two levels — as a very funny, self-conscious, utterly uninhibited confession of the kind men rarely make (one continually thinks, How can Roth say such things in what will surely be read as an autobiographical work?), and as an experimental novel, in which the author is consciously “writing” a series of stories, chapters, analyses, and summaries, some of which are the desperate fictional constructions of his hero, Peter Tarnopol.

Tarnopol is a writer, highly praised, at the start of what should be a fine career, yet his marriage to an impossible woman named Maureen seems to be destroying him: out of his frantic misery come attempts at fiction, attempts at transforming his life into art, which are ultimately abandoned in favour of what Roth calls “My True Story”.

The novel is experimental, also, in its constant questioning of the basic assumptions of literature, and in its hero’s exasperated, humiliated recognition that whatever “art” is, his personal life does not resemble it in the slightest. Arguing, fighting, weeping, enduring an impossible but interminable relationship with his wife — who will not grant him a divorce — the young Tarnopol sees that he is not a character in a serious novel at all, but in a kind of soap opera. At one point Maureen herself is imagined as saying: “You want subtlety, read The Golden Bowl. This is life, bozo, not high art.”

My Life as a Man makes the point, as Portnoy’s Complaint does also, that being a “man” is difficult, if not impossible: one can be reduced to a child, a little boy, by the manipulations of other people. In Roth, the nemesis is usually a woman, as it is usually a paternal figure in Kafka, but both Roth and Kafka deal with endlessly analytical heroes who believe themselves constantly on trial and constantly failing, unable to live up to standards of adulthood that seem to come easily to other people.

Maureen, the Terrible Female, is killed in an automobile crash which she might have caused, in a moment of anger, and so Peter Tarnopol is “free”. Or should be free. He is, at least, no longer married. But at the novel’s conclusion he is beginning to realise that Maureen may be more of an obsession to him now that she is dead, than when she was living; and in any case, he is still himself: “This me who is me being me and none other!”

***

A version of this piece first appeared on Joyce’s Substack.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe